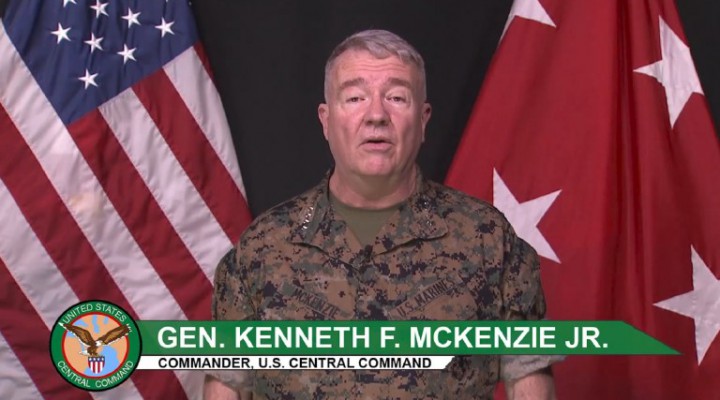

How CENTCOM Chief McKenzie manufactured an Iran crisis to increase his power

Seeking prestige and power within the military, CENTCOM chief Gen. Kenneth McKenzie has deployed a series of bureaucratic and PR moves to drive the latest episode in US-Iran tensions.

During the final two months of the Trump administration, a series of provocative U.S. military moves in the Middle East stirred fears that a war against Iran was being hatched. The atmosphere of crisis was not the result of any threat posed by Tehran, but rather the product of a campaign manufactured by the head of US Central Command (CENTCOM), Gen. Kenneth F. McKenzie Jr., to advance his interests.

In a bid for prestige and power within the military, and the influence over policymaking that it guarantees, McKenzie has worked to accumulate military assets. The general’s thirst for influence has been a driving factor in the latest episode of US-Iran tensions. To advance his self-serving agenda, McKenzie has deployed a calculated series of political-bureaucratic moves, combined with a PR push in the media.

A four-star general who previously served as director of the Joint Staff at the Pentagon, McKenzie is regarded as the most politically astute commander ever to lead Middle East Command, according to journalist Mark Perry. He has also shown himself to be exceptionally brazen in scheming to defend his interests.

Almost immediately after taking command at CENTCOM in March 2019, McKenzie launched his campaign of political manipulation. By requesting additional forces to contain a supposedly urgent Iranian threat, McKenzie triggered the dispatch of an aircraft carrier strike group and a bomber task force to the Middle East. A month later, he told reporters he believed the deployments were “having a very good stabilizing effect,” and that he was in the process of negotiating on a larger, long-term U.S. military presence.

As a result of his maneuvering, McKenzie succeeded in acquiring 10,000 to 15,000 more military personnel, bringing the total in his CENTCOM realm to more than 90,000. The rapid increase in assets under his command was revealed in a Senate hearing in March 2020.

During the remainder of 2020 some of those troops were shifted to East Asia or Europe, in line with the new Pentagon priority on “major power competition.” McKenzie’s determination to resist the loss of military assets was a crucial factor in artificially manufacturing the recent Iran crisis.

McKenzie has fought to keep thousands of U.S. troops in Iraq, ostensibly to fight ISIS, but more fundamentally to maintain a long-term military presence in the country. But the U.S. military presence has been extremely unpopular in Iraq. In January 2020, following the U.S. assassination of Iranian Maj. Gen. Qassem Soleimani, Iraq’s legislature passed a resolution demanding the withdrawal of all U.S. troops from the country.

In the meantime, Iraqi militias aligned with Iran have escalated attacks on U.S. forces, beginning with a major rocket attack on coalition forces at Camp Taji in March 2020 that killed two U.S. servicemen. McKenzie exploited the Camp Taji attack to reclaim some of the assets he had lost, successfully requesting that a second aircraft carrier strike group remain in the region. McKenzie asked for the additional forces, according to the Wall Street Journal, to “signal to Tehran that it would be held responsible” if the Iraqi militias continued to attack U.S. forces.

But that ploy was quickly shown to be a failure: Iraqi militia attacks on bases occupied by U.S. forces soared to 28 between March and August 2020. McKenzie was thus forced to begin withdrawing from bases in Iraq and turning them over to Iraqi forces. In September, McKenzie even acknowledged, while announcing the planned reduction of U.S. troops in Iraq from 5,200 to 3,000, that militia attacks were a major reason for the withdrawal.

After Trump’s mid-November decision to reduce troop numbers in Afghanistan and Iraq to 2,500, McKenzie and his allies in Washington constructed the illusion of a crisis with Iran by promoting the idea that Iran might be planning attacks on U.S. forces.

The New York Times reported on November 16 that officials were “especially nervous about the January 3 anniversary of the U.S. strike that killed Soleimani….” And a Washington Post story the following day cited “people familiar with the matter” stating that U.S. intelligence had recently been “monitoring potential threats by Iran to U.S. forces in the region”.

Then came an even more serious move: on November 21, two Air Force “Stratofortress” B-52 bombers flew directly from the United States to the Persian Gulf.

The flight was announced in a statement by the spokesman for McKenzie’s Central Command, which offered no specific justification. It declared that the Soleimani assassination in January 2020 precipitated the last deployment of long-range B-52 flights to the Gulf, creating the sense that the new flights were linked to a potential military crisis. In fact, the bombers made a round-trip from their U.S. base to the Gulf and back without stopping.

On December 7, McKenzie was back on the PR offensive, speaking to a small group of reporters who were allowed to identify him only as a “senior U.S. military official with knowledge of the region.” As the Associated Press and NBC News reported, he said the risk of miscalculation by Iran “is higher…right now,” because of the U.S. pulling troops out of the region, the U.S. presidential transition, the COVID pandemic, and the anniversary of Soleimani killing. He emphasized that military leaders had determined that the Nimitz must remain in the region “for some time to come,” and that an additional fighter jet squadron might also be needed.

Three days later, another squadron of B-52s flew from the U.S. to the Persian Gulf, flying provocatively close to Iranian airspace before returning to their home base. Then, on December 21, the U.S. Navy publicly announced that the guided-missile submarine USS Georgia, along with two guided-missile cruisers, had just transited the Strait of Hormuz and entered the Arabian Gulf. The announcement was highly unusual: the Navy, normally tight-lipped about the movements of its ships, stated publicly that the Georgia could carry up to 154 Tomahawk land-attack cruise missiles.

In an interview with ABC News on December 22, McKenzie was asked about the risk of an Iranian attack on US and allies in the region. “I do believe we remain in a period of heightened risk,” he said, even though he also suggested that Iran did not want war with the United States.

A third flight of B-52s was dispatched to the Persian Gulf on December 30. This time, CENTCOM quoted McKenzie directly: his intention was to “make clear that we are ready and able to respond to any aggression directed at Americans or our interests.”

A “senior military officer” subsequently told the Associated Press that U.S. intelligence had supposedly detected “indications that advanced weaponry has been flowing from Iran into Iraq recently and that Shiite militia leaders in Iraq may have met with officers of Iran’s Quds force.” This was said to suggest plans for possible rocket attacks against U.S. interests in Iraq, in connection with the one-year anniversary of the Soleimani killing. CNN echoed the Pentagon claims, alleging that Iran had moved short-range ballistic missiles into Iraq, and that Iraqi militias were planning “complex attacks.”

But a “senior defense official” who had been directly involved in the discussions of those issues insisted to CNN that officials circulating such reports were deliberately exaggerating the threat of an attack. The CNN story strongly implied that acting Secretary of Defense Christopher Miller’s December 30 decision to bring the Nimitz back home was based on his belief that McKenzie and his allies were hyping a potential Iranian-sponsored attack to advance their command’s interests.

Neither the Associated Press nor CNN explained to readers that the additional Iranian short-range missiles would have been been necessary precautions to strengthen deterrence in light of the series of the provocative U.S. shows of force involving B-52s and missile-carrying ships. Nor did they mention explicit statements by Iran that revenge for the Soleimani killing would be aimed not at U.S. troops but at the officials responsible for his assassination.

In the end, Miller was forced to reverse his decision and keep the Nimitz in the Middle East — a significant win for McKenzie. And although the anniversary of the U.S. assassination of Soleimani came and went without incident, yet another flight of B-52s was carried out on January 7 — a bold demonstration of McKenzie’s bureaucratic victory over Miller.

The political-bureaucratic power struggle that played out in the final weeks of the Trump administration suggests that McKenzie’s power and interests are likely to be a major influence on the Biden administration’s Iran policy.

Still resisting the shift of military assets away from the Middle East, McKenzie will have a strong motive to oppose and obstruct any effort at easing tensions with Tehran. To achieve his aims, his ties with the military services and media will be among the most useful weapons in his arsenal.

How CENTCOM Chief McKenzie manufactured an Iran crisis to increase his power

TheAltWorld

TheAltWorld

0 thoughts on “How CENTCOM Chief McKenzie manufactured an Iran crisis to increase his power”