Iran’s elections and the nuclear talks

Tehran will be a tougher interlocutor under its new president

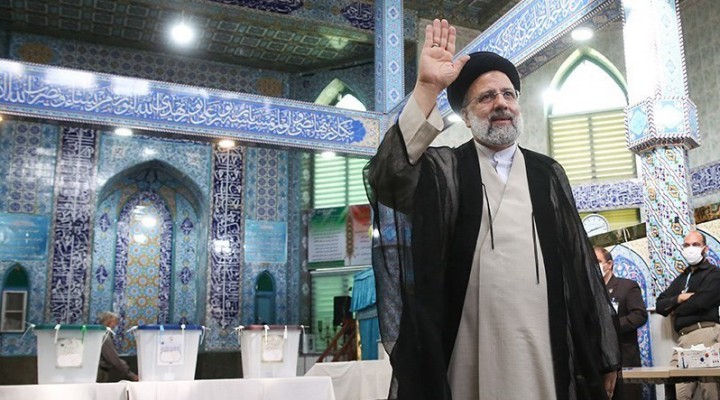

With the election of Ebrahim Raisi to succeed the ‘reformist’ Hassan Rohani after the end of his presidential second term, a new phase is beginning in Iran. Its key feature is the ascendancy of the ‘revolutionary’ wing of the regime more powerfully than ever before. For the first time since the death of Imam Khomeini, it will control all three branches of government – legislature, judiciary, and executive – under the direct supervision of Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei.

The significance of electing a strong and resolute figure, a member of the Mashhad religious elite with a reputation for siding with the poor and deprived and combating corruption and the corrupt, can be gauged from the hysterical Israeli response that began the moment Raisi’s win was announced. Israeli politicians and analysts are convinced that after he takes office in mid-August he will strive to further strengthen Iran’s military capabilities and possibly make it a member of the international nuclear club.

The new Iranian president, who is widely seen as Khamenei’s favoured choice to succeed him, will face three main challenges once he forms his administration.

First, to tackle the suffocating economic crisis afflicting the country because of US sanctions.

Second, the negotiations with the US and the other five big powers about reviving the JCPOA nuclear deal.

Third, relations with Gulf neighbours and Iran’s place in the shifting pattern of global alliances and the emergent China-Russia axis.

These challenges are closely interlinked and cannot be tackled separately. As a protégé of Khamenei who has been groomed for this position for years, Raisi and the ‘revolutionary’ team he puts together can be expected to have a clear roadmap of where they intend to go an all three fronts.

It was no secret that Khamenei was dissatisfied with the performance of Rohani and his government over the past eight years, especially their failure to achieve economic prosperity and ease the suffering of ordinary Iranians. Trump’s withdrawal from the JCPOA in 2018 and imposition of draconian new sanctions made matters worse. This prompted Khamenei to change course, prepare the ground for Raisi to assume the presidency, and wait for him to take over before considering the concessions made by the Biden administration at the Vienna talks on reviving the JCPOA.

Raisi’s election is expected to strengthen Iran’s hand at the negotiations and increase pressure on the US to make more concessions regarding the full lifting of sanctions and recognising Iran’s role in the region – especially with the Biden administration pulling forces and air defence systems out of the Middle East so as to focus on China and East Asia. American hopes that the Vienna talks can be concluded before Raisi takes over are probably misplaced. Iran’s supreme leader will not want to gift that achievement to the ‘failed’ Rohani.

Under its new president, Iran will be an interlocutor of a very different kind.

https://www.raialyoum.com/index.php/irans-elections-and-the-nuclear-talks/

TheAltWorld

TheAltWorld

0 thoughts on “Iran’s elections and the nuclear talks”