What if Iran Retaliates and Shuts Down the Strait of Hormuz?

Some 18 million barrels of oil transit through every day. The economic impact would be catastrophic.

The effort on the part of the Trump administration to shut down Iran’s ability to export oil is predicated on the false notion that the rest of the world will fall in lockstep with U.S. policy. But has President Donald Trump really thought through what would happen to the economic health of the world if Iran retaliates, shutting the Strait of Hormuz, through which much of the world’s oil flows daily?

The Trump administration’s push to reduce Iran’s oil exports to zero has entered a new, critical phase, with the United States refusing to extend the waivers it granted six months ago to eight nations, including China, India, Turkey, Japan, and South Korea, to purchase Iranian oil. Moreover, the United States has refused to allow for a “wind-down” period where impacted nations would be able to gradually wean themselves away from Iranian sources of energy. This means that, effective May 1, any nation purchasing oil from Iran will be subjected to punitive U.S. sanctions.

Iran has responded to the American decision not to extend oil waivers in typical fashion, with Rear Admiral Alireza Tangsiri, the commander of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Command (IRGC) naval forces, warning on April 23 that “if Iran’s benefits in the Strait of Hormuz, which according to international rules is an international waterway, are denied, we will close it”.

This threat was clarified the next day, April 24, by Iran’s Foreign Minister, Javad Zarif, who declared “ships can go through the Strait of Hormuz,” noting that “if the U.S. wanted to continue to observe the rules of engagement, the rules of the game, the channels of communication, the prevailing protocols, then in spite of the fact that we consider U.S. presence in the Persian Gulf as inherently destabilizing, we’re not going to take any action.”

For now.

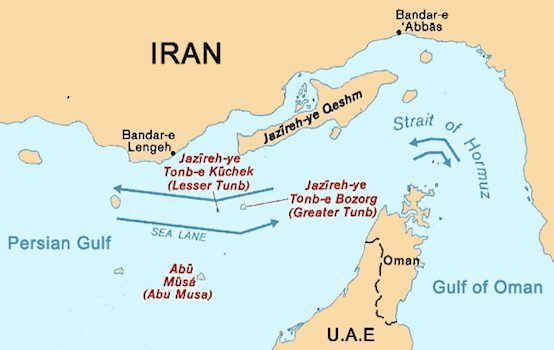

The Strait of Hormuz is one of the most critical sea lanes in the world today, transiting some 18.5 million barrels of crude and refined products per day, representing roughly 20 percent of all oil produced globally. There is universal consensus among energy analysts that any closure of the Strait of Hormuz would result in “catastrophic” consequences for the global economy.

ArmanJan/Wikimedia/public domain.

Less certain is whether Iran is serious about carrying out its threats. In July 2018, following the Trump administration’s decision to withdraw from the Iran nuclear deal (the Joint Comprehensive Program of Action, or JCPOA), Iranian President Hassan Rouhani threatened to close the Straits in retaliation for renewed U.S. economic sanctions. Calmer heads prevailed, and Iran ended up taking the diplomatic route, working with the other signatories of the JCPOA to find ways to bypass U.S. sanctions.

In the intervening time, Iran’s efforts at crafting a diplomatic solution have fizzled, with Europe unable (or unwilling) to implement a meaningful alternative to the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT) system, a financial network based in Belgium that provides cross-border transfers for over 11,000 financial institutions in more than 200 countries and territories around the world. Because the SWIFT board includes executives from U.S. banks, federal law allows the U.S. government to sanction banks and regulators who operate in violation of U.S. law. As such, any financial transaction involving Iran or any other entity under U.S. sanction would provide a trigger for secondary sanctions to be applied to facilitating institutions and/or persons.

Iran has a history of bypassing U.S. sanctions, and while the Trump administration’s targeting of Iran’s oil exports has caused significant economic harm to the Islamic Republic, Iran remains confident that it would be able to continue to sell oil in enough quantity to keep its economy afloat. In a recent appearance, the Supreme Leader of the Islamic Revolution, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, declared that the American effort to block Iran’s oil sales will fail. “The Islamic Republic of Iran will be exporting any amount of oil it would require, at will,” Khamenei said.

There is a major difference between 2018 and today, however. The recent decision by the Trump administration to declare the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Command (IRGC) a terrorist organization has complicated the issue of Iran’s oil sales, and America’s reaction in response.

The IRGC has long been subject to U.S. sanctions. In 2012, the U.S. Department of Treasury, Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), determined that National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC) was an “agent or affiliate” of the IRGC and therefore is subject to sanctions under the Iran Threat Reduction and Syria Human Rights Act of 2012 (ITRSHRA). Other Iranian oil companies have likewise been linked to the IRGC, including Kermanshah Petrochemical Industries Co., Pardis Petrochemical Co., Parsian Oil & Gas Development Co., and Shiraz Petrochemical Co.

While in 2012 the United States determined that there was insufficient information to link the National Iranian Tanker Company (NITC) as an affiliate of the IRGC, under the current sanctions regime imposed in 2018 the Islamic Republic of Iran Shipping Lines (IRISL) and the NITC have been blacklisted in their entirety.

By linking the bulk of Iran’s oil exporting capacity to the IRGC, the United States has opened the door to means other than economic sanctions when it comes to enforcing its “zero” ban on Iranian oil sales. Any Iranian oil in transit would be classified as the property of a terrorist organization, as would any Iranian vessel carrying oil.

Likewise, any vessel from any nation that carried Iranian oil would be classified as providing material support to a terrorist organization, and thereby subject to interdiction, confiscation, and/or destruction. This is the distinction the world is missing when assessing Iran’s current threats to close the Strait of Hormuz. It’s one thing to sanction Iranian entities, including the IRGC—Iran has historically found enough work-arounds to defeat such efforts. It is an altogether different situation if the Unite States opts to physically impede Iran’s ability to ship oil. This would be a red line for Iran, and a trigger for it to shut down all shipping through the Strait of Hormuz.

So far the United States has not shown any inclination to physically confront Iranian shipping. Indeed, as Iran’s top military commander Major General Mohammad Baqeri recently told reporters, U.S. naval and commercial vessels transiting the Strait of Hormuz continue to respond to the queries transmitted by the IRGC naval forces responsible for securing Iran’s portion of the strategic waterway—an awkward reality given that the IRGC has been designated a terrorist organization, which means the U.S. Navy freely communicates and coordinates with terrorists.

“As oil and commodities of other countries are passing through the Strait of Hormuz, ours are also moving through it,” Bageri observed, declaring that “if our crude is not to pass through the Strait of Hormuz, others’ [crude] will not pass either.” Bageri went on to explain that “this does not mean [that we are going to] close the Strait of Hormuz. We do not intend to shut it unless the enemies’ hostile acts will leave us with no other option. We will be fully capable of closing it on that day.”

The challenge will come when the U.S. effort to bring Iran’s oil exports to zero fails—and most observers believe this will be the case. Iran’s Foreign Minister Javid Zarif has bragged that “Iran has a PhD in sanctions busting,” and historical precedence is on his side. If the Trump administration proves unable to shut down Iran’s ability to sell oil through sanctions, and therefore fails to blunt what it describes as Iran’s “malign activities” in the Middle East, there will be increased pressure to be seen as doing something—anything—to effectuate policy objectives, especially during the lead up to the 2020 presidential election, where the Trump administration would be loath to provide any fodder to its political opponents.

Because any effort to restrict or deny transit through the Strait of Hormuz would be rightfully seen as a provocative act worthy of military intervention, it is highly unlikely that Iran would take any precipitous action in that regard. Instead, Iran would most likely seek a gradual escalation of restrictions grounded in its legal interpretation of the 1982 United Nations’ Convention on the Law of the Sea, which grants Iran control over “territorial waters” extending to a maximum of 12 nautical miles beyond its coastline. Any ships using the northern and eastern routes through the Strait of Hormuz to gain access to the Persian Gulf would have to transit through Iranian waters.

Under the convention, Iran is permitted to deny free transit passage to nations, like the United States, which have not ratified the agreement. If the United States interdicts Iranian shipping involved in the transit of oil, then it is most likely Iran will close the Strait of Hormuz to U.S. shipping, citing the 1982 convention as its justification. The United States would either be compelled to back down (unlikely), or resort to military force, certifying it as the aggressor in the eyes of international law.

The military debate over Iran’s ability to close the Strait of Hormuz, and the U.S. ability to respond to such a threat, is moot—no insurance company will cover any oil tanker seeking to transit contested waters. The economic impact of any closure will be immediate, catastrophic and sustained. Even if the United States prevailed in a military conflict over the Strait of Hormuz (and it is not certain it would do so), any victory would be pyrrhic in nature, with the United States sacrificing its national economic health, and that of the rest of the world, on an alter of hubris that fails to advance the national interest in any meaningful fashion.

https://www.theamericanconservative.com/articles/what-if-iran-retaliates-and-shuts-the-strait-of-hormuz/

TheAltWorld

TheAltWorld

0 thoughts on “What if Iran Retaliates and Shuts Down the Strait of Hormuz?”