Biden’s defense secretary pick Austin challenges US civil-military balance at a time when it’s crucial to preserve it

In picking Lloyd Austin to be his secretary of defense, Joe Biden has placed personal preference over national security. General Austin is the wrong man for the job, and the US Senate should not confirm his nomination.

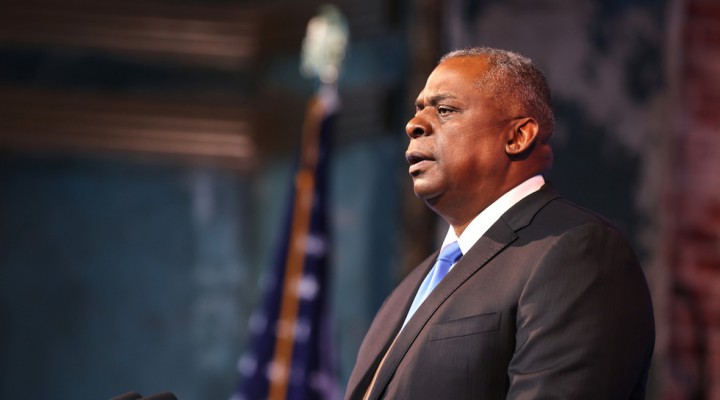

Biden’s choice of retired US Army General Lloyd Austin marks the first time that a black man has been nominated to serve as the senior civilian manager of the nation’s defense. While there is no doubt that Austin’s experience lends itself to carry out these challenges in a competent and professional manner, it is this very resume that creates the greatest obstacle for the retired general from serving as Congress intended a secretary of defense to serve – as the senior civilian adviser to the president on matters pertaining to the defense of the country. Austin’s military experience makes him the wrong man for the job and could lead to a contentious Senate confirmation process whose outcome is far from guaranteed.

Over the course of a 40-plus-year career, the retired general has served honorably in several high-profile positions, including as the commander of US Central Command, responsible for overseeing US military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. It was his tenure as the last commander of US combat forces, in 2011, that led Biden to give Austin the nod.

As Barack Obama’s vice president, Biden had been intimately involved in overseeing the winding down of US combat operations in Iraq, and he and Austin established a solid rapport during that time. It was this good working relationship which drew Biden to nominate Austin. “The threats we face today are not the same as those we faced 10 or even five years ago,” Biden wrote when discussing his decision to nominate Austin. “We must prepare to meet the challenges of the future, not keep fighting the wars of the past.”

But a deeper look at Austin’s resume shows that the very experience which makes him attractive to Biden underscores his weakness as the nation’s top civilian defense official. At a time when the Obama administration had made a political decision to end the US combat mission in Iraq, General Austin fought not only to keep the mission alive, but to dispatch more troops for an expanded operational footprint designed to achieve the ever-elusive “victory” on the battlefield that neither Austin nor any of his predecessors had been able to obtain.

Moreover, Austin’s intransigence at the negotiating table ended up precluding a deal with Iraq, compelling the US to depart in a far weaker position than could have been achieved if he had shown a modicum of the kind of diplomatic flexibility he will be called upon to demonstrate as secretary of defense.

Austin’s drive to win at any cost might be a desirable trait for mission-oriented military officers, but it is not the kind of thinking one wants – or needs – as a civilian leader called upon to decide if and when a war is no longer politically viable.

When creating the position of secretary of defense in 1947, the US Congress passed a law which barred general officers from serving in that position within seven years of their retirement (Austin retired four years ago). The purpose of the law was to help preserve the civilian aspect of the job. The president already had access to the advice of military general officers in the form of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. The role of a secretary of defense is not to echo the opinions of the serving military, but rather to provide advice derived from a political perspective divorced from – and often in conflict with – that of senior military leadership.

Austin, meanwhile, has spent the last four years on the board of Raytheon, a major US defense contractor, and is a partner at Pine Island Capital, an investment company which also employs Biden’s secretary of state nominee Antony Blinken, and Michele Flournoy, widely considered a candidate for a senior position in the Biden administration. Unlike Blinken and Flournoy, both of whom never served a day in the military and embody a civilian mindset, the perspective of Austin’s 40-plus-year military career cannot be reprogrammed by a few years of defense consulting.

A future Biden administration will find itself undergoing significant military restructuring which will challenge many legacy beliefs and traditions. If confirmed, Austin would be called upon to oversee a department during a critical transition away from decades of low-intensity conflict in the Middle East and Southwest Asia, instead positioning the US military to be better able to confront peer-level opponents in Europe and Asia.

Virtually every aspect of the nation’s defense, encompassing budgets, doctrine, personnel, and equipment, will be subjected to scrutiny during this transition. Decisions will be made about strategic nuclear weapons, naval expansion, Marine Corps restructuring, rebuilding a depleted army, and acquiring the next generation of combat aircraft. The military tends to ask for everything. The fiscal constraints of a post-pandemic reality mandate that the secretary of defense must be willing and able to say no.

Many of the choices that will be put before the secretary of defense will be controversial, requiring them to balance political reality with military necessity to make decisions that have the potential of being hotly contested by the senior military leadership. As a recently retired general, Lloyd Austin embodies much, if not all, the legacy beliefs and traditions that will be subjected to change – sometimes radical – as the US moves forward to meet the new challenges posed by the post-Global War on Terror world.

As secretary of defense, Austin would likely oversee budgets that were averse to change, doctrine that remained inflexible, and – in keeping with his past practice in Iraq – evince a tendency to keep the “forever” in America’s current forever wars in the Middle East and Southwest Asia. Simply put, he is conditioned to think and act like a general. He does not have the demonstrated capacity to function as a civilian who would place political reality above the entrenched, often myopic interests of the military.

Austen’s nomination represents the third time in history Congress will be called upon to grant a waiver to the seven-year gap in service. The first was for General George C. Marshall, and the second for James Mattis. The results of these waivers were mixed – while Marshall proved to be the right man for the job, Mattis was a disappointment, unable to break free from the Marine Corps mentality which was ingrained into his DNA. Senator Jack Reed, the senior Democrat of the Armed Services Committee, made it clear after Mattis’ waiver that he would not be inclined to support another, lest a tradition be established.

Civilian leadership of the US military is a cornerstone feature of US civil-military relations. Austin’s nomination challenges this at a time when such bedrock principles should be left unchanged. The next four years will prove to be challenging for the US defense establishment, which needs someone at the helm who is willing and able to make the tough decisions regarding much-needed change. Lloyd Austin, unfortunately, is not this person.

TheAltWorld

TheAltWorld

0 thoughts on “Biden’s defense secretary pick Austin challenges US civil-military balance at a time when it’s crucial to preserve it”