We’ll march forward,

Like we marched with you.

And with Fidel we will tell you,

Until Forever, Comandante!

The Nueva Cancion Chilena’s pioneers Angel Parra, Isabel Parra and Rolando Alarcon represented Chile at the musical gathering. Angel and Isabel Parra in particular attracted much attention at the festival — their mother, Violeta Parra, was a Chilean composer, singer, songwriter, and ethnomusicologist who was partly responsible for starting the Nueva Cancion Chilena movement. Her research on Chilean folk music throughout the country and her political activism led to her setting up, along with her children, the Peña de Los Parra, an art gallery and cultural club in Santiago where Nueva Cancion musicians met and performed live. Despite her humble beginnings, Parra’s influence on the Chilean protest song movement would significantly impact Chilean politics and culture. She committed suicide at the age of 49, in February 1967, leaving behind an influential legacy.

INTERTWINED PHILOSOPHIES, DISTINCT ROOTS

While the Nueva Cancion Chilena and the Nueva Trova Cubana movements were founded within years of each other, in 1965 and 1967 respectively, both emerged out of different social realities.

In Cuba, the Nueva Trova Cubana, pioneered by Puebla, Pablo Milanes, Silvio Rodriguez and Vicente Feliu, enjoyed the revolutionary government’s support. Drawing upon the roots of Cuban music, the Nueva Trova Cubana provided a vehicle for anti-imperialist and pro-revolutionary sentiment. The Cuban style was very influential in the region, it was “an exciting experiment in the construction of a Latin American musical tradition that was both politically progressive and aesthetically pleasing,” according to Murray Luft, a musicologist who spent over 25 years in Latin America, in a book discussing the militant song movement in Latin America. He characterized Nueva Trova Cubana as incorporating popular socialist sentiment against a backdrop of Cold War politics, and spreading in the region, especially among those opposing military regimes.

In contrast, the Nueva Cancion Chilena had no government backing in its early stages. In a brief correspondence I had with the late Patricio Manns, one of the founders of the musical style, he described the movement as beginning with Angel and Israel Parra, Victor Jara, Rolando Alarcon and Manns himself. The movement soon inspired others across Chile, at a time when the Chilean presidency was in the hands of Christian Democrat Eduardo Frei. Frei served as Chile’s president from 1964 until 1970 and his 1964 election campaign was covertly backed by the CIA in a bid to counter Allende. Frei’s social reforms in health, agriculture and education were met with staunch opposition by Chile’s business elites, whose support for Frei was only based on him being the only alternative to Allende.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HQm_xnq52CA

During Salvador Allende’s electoral campaign in 1970, Nueva Cancion musicians were folded into the political sphere when they pledged their commitment to the Unidad Popular’s program, which recognized imperialist influence in Chile and sought to combat it through social reforms and the nationalization of natural resources. A collaboration between Jara, Alarcon, and Sergio Ortega paved the way for the hymn Venceremos, which became synonymous with Allende’s Unidad Popular. When Allende became president in 1970, Nueva Cancion musicians toured abroad as part of Chile’s cultural movement, supported by the government. The first Nueva Cancion Chilena festival was held in 1969 in which Victor Jara sang Plegaria a un Labrador (Prayer to a Peasant). The song earned him first place, tied with Richard Rojas.

But Allende’s cultural initiative, and the brief foray into state-sponsored music, violently ended after the US-backed coup in 1973. Augusto Pinochet’s US-backed dictatorial regime persecuted Nueva Cancion Chilena musicians. After being recognized as a Nueva Cancion singer, Jara was singled out for brutal torture and later murdered at the Estadio Chile in September, a venue that became one of the first detention and extermination sites in the early days of the dictatorship. The Chilean folk band Inti Illimani was on tour in Italy when the coup occurred. They remained in exile and their music was banned in Chile, while other musicians such as Angel Parra were detained, tortured, and later exiled.

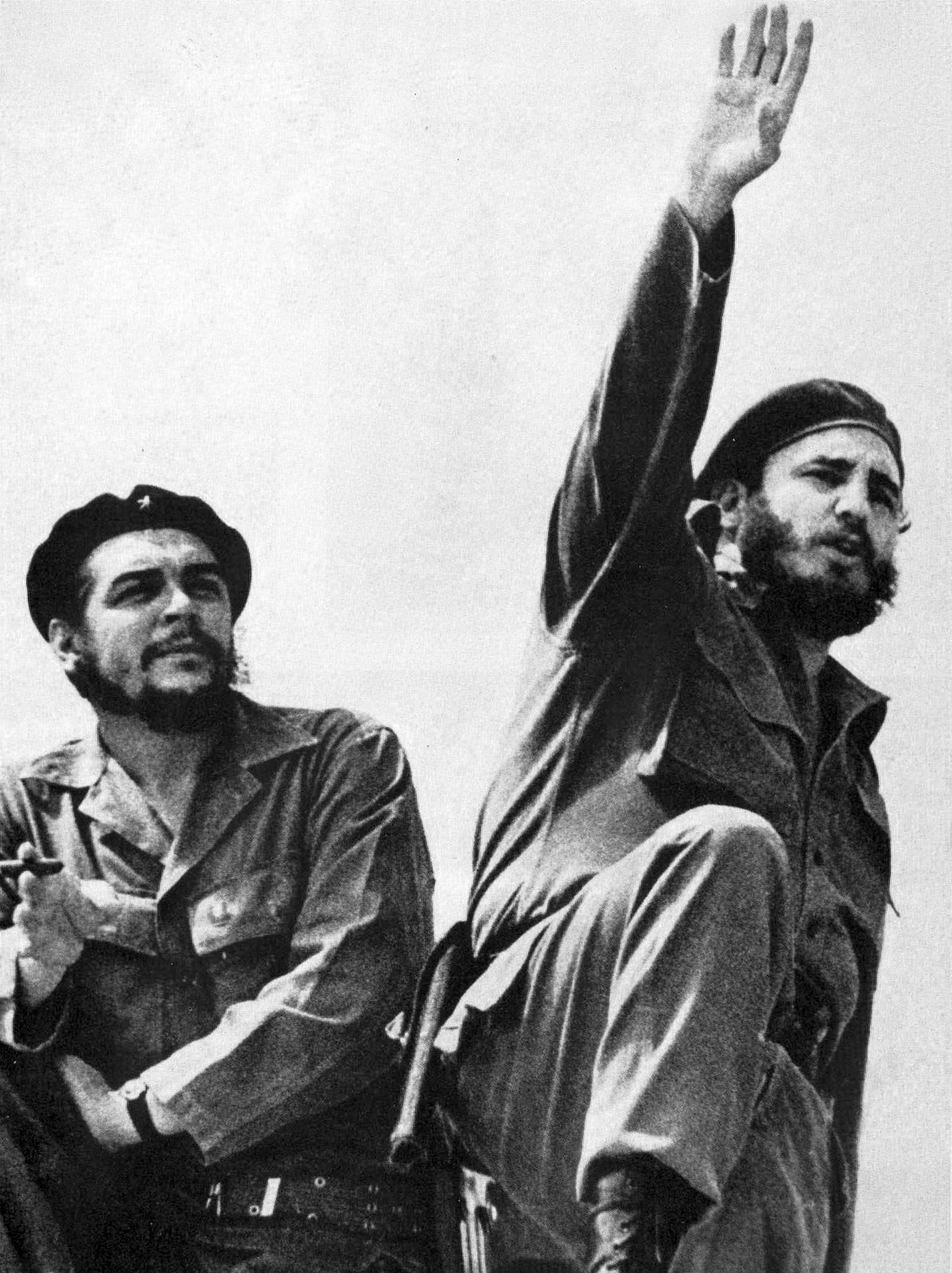

Before and after the coup, links between musicians in Cuba and Chile were prominent. In 1959, Jara had traveled to Cuba and met with Che. In late 1973, a few months after the Pinochet coup, Manns was able to leave Chile for Cuba due to diplomatic intervention, he later settled in France and became a vocal critic of the dictatorship, while continuing his musical career with the group Karaxu. Fidel’s visit to Chile in 1971 prompted him to declare Allende’s electoral victory as “the most important revolutionary triumph in Latin America after the Cuban Revolution.” The US clearly agreed, but found the movement threatening. Chile became a target for the neoliberal experiment imposed by the Chicago Boys — an elite group of neoliberal Chilean economists who had trained in Chicago under Milton Friedman. Their policies ushered in decades of inequality that endures to this day.

NOSTALGIA AND RENAISSANCE

Chile now has a new government under President Gabriel Boric, which is actively working to reconfigure power relations and reimagine the Chilean Left. The country is currently writing the first new constitution since the brutal Pinochet regime. It is clearly time for a renovated revolution for the new millennium, as the country faces the laborious work of untangling and dismantling the impacts of decades of US neoliberal policies and the ghosts of dictatorship.

Twelve years ago, Manns reiterated his belief in the development of song in Latin America, despite the fact that many of its pioneers have now passed away. “The Nueva Canción has given extraordinary power to popular song, stripping away the residue of nostalgic memories and patriarchal shadows, replacing them with pride, perseverance, and resistance — these are the materials we are working with.”

While the Nueva Cancion Chilena is mostly linked to Chilean memory nowadays, Chile’s recent foray into nationwide protests which pre-empted the vote to rewrite the constitution shows that there still is a niche for protest music — one that deals with the current social issues while still respectful of its origins and the country’s collective memory.

In today’s political climate, US imperialism has not completely altered its tactics in Latin America. Manns’s words, as well as the internationalist solidarity generated 55 years ago in Cuba, would benefit from a tangible revival.

https://inkstickmedia.com/latin-american-protest-songs-deserve-a-revival/

TheAltWorld

TheAltWorld

0 thoughts on “Latin American Protest Songs Deserve a Revival”