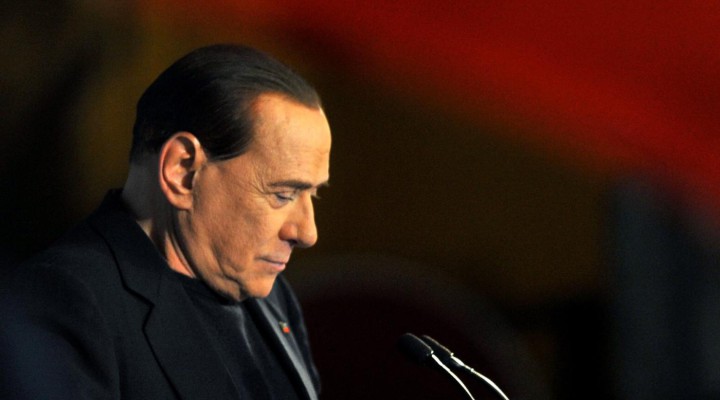

Silvio Berlusconi: The billionaire who radically changed Italian politics

He believed – often wrongly – that his personal relationship with certain foreign leaders could automatically pave the way to a solution to any problem

Former Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi passed away in Milan on Monday at the age of 86 after a long illness.

For nearly five years of my prior professional life, I served as a member of his foreign policy staff. Between 2008 and 2011, I was his deputy foreign policy affairs adviser who oversaw delicate dossiers like the Middle East and North Africa, Russia and the Balkans, counterterrorism, and business promotion.

But as a simple Italian citizen, I can say that, for better or for worse, Berlusconi has had a tremendous influence on the last three decades of Italian politics.

His arrival was a watershed moment in the country and his real legacy will engage legions of historians.

In Italian political jargon, the historical period marked by his public life has been labelled as the Second Republic, as if to underline a break with the first one that had defined the country from the end of the Second World War to the end of the Cold War.

Political bipolarity

In the early 1990s, the so-called “First Republic”, and the Italian political parties which had formed it, collapsed under the blows inflicted by the judiciary with the infamous Mani Pulite (clean hands) scandal focused on widespread corruption rings.

Berlusconi took up the legacy of the democratic centre of the Italian political landscape, represented mainly by the Christian Democratic Party, and opened the way to political bipolarity, especially after the adoption of a majoritarian electoral law that revolutionised the way of doing politics in a country that, until then, had appeared permanently fractured.

He also brilliantly succeeded in unfreezing the main part of Italy’s former fascist or neo-fascist political movements, building a ruling coalition that remained in power for almost a decade in two separate periods.

As a media tycoon, Berlusconi was the entrepreneur who, at the end of the 1970s, introduced commercial television in Italy, breaking state television’s monopoly. It brought a breath of fresh air but also – it must be recognised – vulgarity and triviality to broadcast content.

His success with the Milan soccer team in the 1980s and 1990s put him into the limelight.

There was only one political personality in Italy that Berlusconi was never able to defeat: former prime minister and president of the European Commission, Romano Prodi. Against the latter, he lost both the 1996 and 2006 general elections.

I had the opportunity to work for both leaders between 2004 and 2011. Their respective visions and ways of conducting foreign policy were polar opposites. Both had their own vision and intuition but in Berlusconi’s case, the only option left to his aides was to execute and turn them into viable realities.

Sometimes Berlusconi seemed to prefer the company of autocrats like the late Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi, Egypt’s Hosni Mubarak, and Russia’s Vladimir Putin, whom he envied for their absence of constraints in decision-making, and the absence of the shackles of democratic systems and the stickiness of bureaucracy.

However, having said that, it would be unfair to attribute to him – as many did – autocratic tendencies. In my opinion, he really believed in freedom and democracy.

Russia-Nato vision

In 2002, Berlusconi outlined the vision of a Russia-Nato Council to overcome, once and for all, the legacy of the Cold War. He brought George W Bush and Vladimir Putin together to shake hands on a shared common future that, ideally, should have ended with Russia joining Nato.

His western partners, however, especially on the other side of the Atlantic, never bought such a vision.

Berlusconi did not realise – or probably pretended not to – that the train for Nato’s relentless eastward expansion had already left the station in the 1990s courtesy of the Clinton administration. The tragic lesson of such missed opportunity still resonates today in the blood-soaked Ukrainian prairies.

Similarly, he believed that Turkey deserved a place in the European Union that it had requested since 1960. He believed that it would have been a greater factor of stability for the Eastern Mediterranean and beyond. He developed a quite good relationship with the then-new Turkish political star, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who had become prime minister in 2002.

It had been framed as a Christian liberal leader reaching out to a then moderate Islamist one. Only Franco-German myopia managed to make this project fail. Looking at Turkey’s attitude today, we are undoubtedly facing another great missed opportunity.

Another European duet, this time Anglo-French – with the US leading from behind – sank another one of Berlusconi’s foreign policy initiatives: a strategic Italian partnership with Gaddafi’s Libya aimed at curbing the wave of refugees from North Africa and launching major infrastructural projects in the area. In 2008, he signed a “friendship treaty” with Libya to execute this plan.

French President Nicolas Sarkozy and British Prime Minister David Cameron, however, could not tolerate the privileged relationship that Berlusconi had been able to create with such a complex and mercurial personality as the Libyan leader. Nor could they accept the business opportunity that such a special relationship granted to Italian businesses to the detriment of British and French ones.

Unlike them, Berlusconi had been the only one who was brave enough to go in front of the Libyan parliament to apologise for the Italian colonial past in Libya. Gaddafi was illegally killed in the autumn of 2011, and the rest is a sad history.

In dealing with the EU, Berlusconi had his critical moments. He hated some of the automatism engraved in EU policies and many double standards emanating from Brussels, but, ultimately, he did not bring the relationship to a breaking point.

He had more passion for Atlanticism than Europeanism, sometimes with embarrassing consequences when he would repeat that “in any issue [he] aligned with the US even before knowing which was the American position”.

It was never possible to make him understand that such a stance compromised Italian political leverage towards the US and risked condemning Rome to always be taken for granted by Washington.

Putting out fires

My working experience with Berlusconi was quite challenging. The business executive in him was instinctively diffident towards public service officials – a feeling that increased when the judiciary intensified its action against him.

At times, he was perceived to be surrounded by serial leakers ready to betray him. He alternated between humility, especially in his first years in power, with excessive confidence.

He had no extensive international experience but pretended to know more and better than his aides based only on the fact that he knew life and the world better because he had become a billionaire.

While such qualities may be good in business, they do not necessarily apply to world politics. He often had the mistaken attitude of hyper-personalising international problems. He believed – often wrongly – that his personal relationship with certain foreign leaders could automatically pave the way to a solution to any problem. He ignored the fact that differing interests between states generally go far beyond single political personalities no matter how talented they might be.

Given this context, if I were to summarise my job description next to him, it would be as a firefighter. Most of the time, the other staffers and I were mobilised to do damage control after his legendary gaffes with foreign leaders and media.

The strong bond Berlusconi developed with George W Bush pushed him to support the US invasion of Iraq in 2003. However, he did so without committing troops to the conflict. Italian soldiers arrived in Iraq in 2004, after the UN Security Council adopted resolution 1483 which authorised an international mission to stabilise Iraq. Nevertheless, privately Berlusconi was always skeptical about the presence of WMDs in Saddam Hussein’s Iraq.

Berlusconi was also a staunch supporter of Israel and its right to exist within secure borders while he always displayed a far more lukewarm attitude towards Palestinian rights. He effectively shifted permanently the Italian position from one of strong support for the Palestinian cause to one far more supportive of Israel.

His personal relationship with Erdogan collapsed precisely over irreconcilable views on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict after a stormy phone call that I shamefully attended during Israel’s Operation Cast Lead against Gaza in December 2008-January 2009.

Even if I sometimes disagreed with Berlusconi’s style and politics, as an Italian, it was painful to watch him be ridiculed in 2011 by his peers, Sarkozy and then-German Chancellor Angela Merkel, in an unforgettable press conference.

Populist policies

Berlusconi’s histrionic manner of policymaking spawned a horde of emulators around the world – from Hugo Chavez to Jair Bolsonaro, Erdogan, Donald Trump, and Boris Johnson.

The first iteration of populist policies in the world was Berlusconi’s period in power in Italy. In this sense, for many, Italy was a disgraceful political laboratory. Although Berlusconi was the real founder of an imaginary “Populist School of Politics and Government”, in private and confidential talks, he showed much more caution and common sense.

One of his main shortcomings in domestic as well as international politics was that he preferred to be surrounded by yes-men and sycophants. They often warped his vision and policies by systematically telling him what he wanted to hear instead of the sometimes difficult truth. The few who attempted in good faith to better promote Italian national interests by providing different views and options were usually kept at bay. Many left or were often compelled to leave. I was among them.

He was the leader who twice had the chance to radically change Italy into a mature and authentically liberal democracy, but he largely failed.

He never gave up his private lifestyle, summarily labelled “bunga bunga”, which saw dozens of young attractive girls – to whom no background check had been carried out and who could keep their own mobile phones – entertained at his private residences. It was never possible to make him fully aware that such gatherings presented worrying security risks.

The Italian judiciary never gave him respite, with dozens of indictments almost always resolved in acquittals which largely compromised his ability to operate effectively.

Berlusconi always had a thorny relationship with the media, in Italy and outside, especially in the UK press. The Financial Times and the Economist were among those that systematically attacked him, considering him unfit to rule. The real reason was that Berlusconi, contrary to what many in Italy now claim, had embraced “sovereigntist” Italian nationalism.

He supported economic liberalisation, but was resolutely against the sell-offs at bargain prices to foreign investors of entire components of the country’s industrial system that have so frequently characterised Italy since 1992.

Berlusconi’s critics largely represented these foreign interests and treated Berlusconi as an obstacle to opening Italy to global capital. Unfortunately, the late prime minister never listened to one of the few good advisers surrounding him who urged him to solve the problem by purchasing both the Economist and FT.

Berlusconi never properly learned the real lesson of power in western democracies that his alter ego in the media world, Rupert Murdoch, has so effectively displayed for decades in the US, UK, and Australia. The real power is not held by those who are “elected” by the people, but by those who influence the people on how they should vote: the owners of great media conglomerates.

Unfortunately, for him, Berlusconi wished more to be king than kingmaker; he found the limelight irresistible. Probably, as a kingmaker, he would have faced far fewer troubles in his nevertheless lucky lifetime.

https://www.middleeasteye.net/opinion/italy-silvio-berlusconi-death-politics-changed-how

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of The Alternative World.

TheAltWorld

TheAltWorld

0 thoughts on “Silvio Berlusconi: The billionaire who radically changed Italian politics”