Giorgia Meloni: What comes next after Italy’s political earthquake?

With the Brothers of Italy party now the country’s largest, and its leader Giorgia Meloni poised as new prime minister, Italy is set to lurch to the right. The key question is how far

Elections are periodically held by mature democracies to give to the people the power to decide who should rule them. Votes are counted and whoever wins is entitled to rule.

As for Italy, this rule usually encounters some adjustments. Votes are not only counted but also weighted. Regardless of the people’s choice, there is an array of powers – formal and informal, inside and outside of the country – that has, in the past, shown that there are views that often are more important and decisive than those of ordinary Italians.

The country’s political establishment has repeatedly given the impression that Italy has constantly needed external tutelage and, in some cases, it has deliberately solicited it. Many Italian politicians have often outsourced their responsibilities and Italy’s sovereignty to external actors.

In the last decades, Italy’s material constitution (the one practically implemented) has evolved. The president of the republic, who has the power to nominate the president of the Council of Ministers taking into account the election results, has progressively assumed the habit of appointing only personalities who guarantee strict adherence to EU values and institutions and those of the political and military umbrella provided by Nato.

The last example of this followed the general election of 2018. The then, and the current, president of the republic, Sergio Mattarella, refused to give the green light to the government of Giuseppe Conte of the populist Five Star Movement because the selected treasury minister, Paolo Savona, was a so-called Eurosceptic. In other words, he had serious reservations about how the EU institutions worked and how Italy had to deal with them. In order to be able to proceed, Prime Minister Conte was forced to replace Savona.

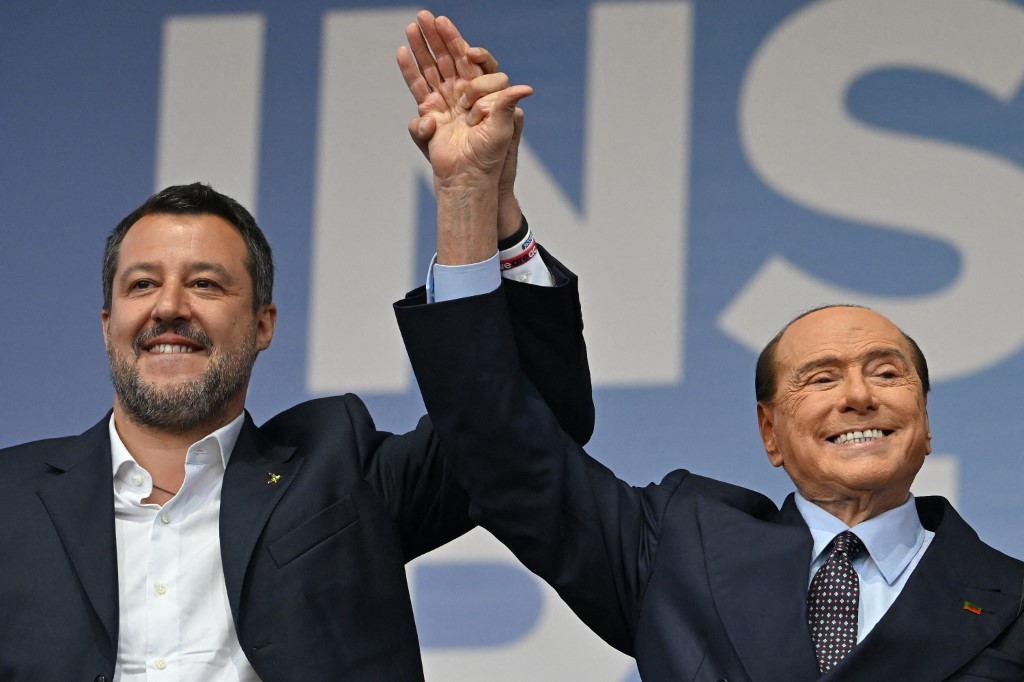

President Mattarella could theoretically do the same with the new Italian government, which will probably be chaired by Giorgia Meloni, the leader of the hard-right Fratelli d’Italia (Brothers of Italy) party. The latter, in coalition with two other right-wing parties (Matteo Salvini’s League and Silvio Berlusconi’s Forza Italia), is the clear winner of the Italian elections held on 25 September.

The ‘Draghi agenda’

Meloni will be the first female prime minister in Italian political history. But her problem is not her gender, but her own history as a former neo-fascist activist who praised Benito Mussolini – and her party’s history that can be traced back to fascism. Brothers of Italy is considered a neo-fascist political movement, even if its leader has worked extensively in recent years to change, or at least to water down, such impressions.

This electoral campaign has mainly focused, sometimes obsessively, on Brothers of Italy’s political roots and on the assurances that the party and its leader could provide about Italy’s continued adherence to EU values and institutions and, also, to the commitments that Nato’s members have made against Russia after its invasion of Ukraine.

Italy’s international position has been carefully observed. Mainstream media has raised significant worries about the election outcome. The ghosts of Viktor Orban’s Hungary have often been evoked. Incidentally, Meloni has praised the Hungarian leader’s sovereign policies on multiple occasions.

As usual, clumsy moves have been present. The US State Department issued a report warning about possible Russian interference in the Italian electoral process, hinting that some Italian politicians were on Moscow’s payroll. No direct evidence was provided.

The president of the EU Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, issued an ambiguous declaration, which sounded like a preventive warning about what Italians were entitled to decide or not.

The leader of Brothers of Italy has been adamant throughout the campaign about her support for the current Italian position against Russia taken by the outgoing prime minister, Mario Draghi, and in assuring European institutions and other EU partners that she would honour all the commitments taken so far in terms of reforms.

The keywords often used during the campaign have been “Draghi agenda” – the assurance that Italy would not move away from the package of reforms that would guarantee the disbursement of the €200bn ($192bn) assigned to the country under the aegis of the EU recovery fund, nor from the tough sanctions adopted against Russia because of the conflict in Ukraine.

Regardless of her efforts, doubts about Meloni’s future government remain in Italy and abroad.

The two junior parties of Meloni’s right-wing coalition, the League and Forza Italia, have both held positions that are controversial, including hostility to migrants and refugees. Leaders of both parties, Salvini and Berlusconi, have repeatedly praised Vladimir Putin and advocated strong bonds with Russia.

A few days before the vote, Berlusconi attempted to justify Putin’s invasion and criticised Ukrainian authorities. Salvini has consistently criticised the effects of sanctions against Russia, which have triggered high inflation and increased dramatically the economic difficulties of ordinary Italians.

Close scrutiny

However, both League and Forza Italia saw their vote share reduced at Sunday’s elections – and especially the League, which dropped from the 17 percent it won in 2018 to 8.8 percent. Brothers of Italy moved from 4 percent in 2018 to 26 percent on Sunday. So it is reasonable to assume that within the coalition there has been a significant transfer of votes.

Meloni will need to carefully steer her government, considering the expectations in Washington and Brussels and the views of her, and her allies’ political base. Her avowed loyalty to Nato and the EU may find criticism in sections of her own party.

Her government will be under close scrutiny, but to claim that Italian democracy is at risk would be premature and a bit ridiculous. The Italian vote confirms a trend that has already been clearly visible in Europe: the rise – sometimes erratic, but constant – of populist right-wing and radical left parties contesting the economic and foreign policies of liberal democracy.

In other words, the opponents of the so-called Davos Party. This was the message conveyed by the presidential and parliamentary elections in France in the spring that saw big vote swings achieved by Marine Le Pen on the far right and Jean-Luc Melenchon on the far left. The same conclusions can be drawn about the Swedish elections earlier this month, with the rise of the far right that has brought a change of government.

At the polls, the Italians (while not forgetting the unprecedented level of abstention – 36 percent) have sent a powerful political message of discontent, with a large majority disavowing the so-called “Draghi agenda”.

Brothers of Italy was always the opposition to the Draghi government; now, with 26 percent of the vote, it is the first party of the country. The populist Five Star Movement – which voted Draghi out of government last July – was considered finished. It has instead increased its support and with 15 percent is now the third Italian party.

Although the League and Forza Italia in coalition supported Draghi, they never missed an opportunity to criticise some of his political acts. Now they are allied with Meloni and, together, have close to 20 percent of votes cast.

If we consider some minor leftist anti-system parties, that together won 5 percent, almost 70 percent of votes cast by Italians in these elections can be thought of as not supporting the political line promoted by Draghi. The latter’s supporters, who are fully supportive of the EU and Nato, barely reached 30 percent.

Politically it is an earthquake, but Italy has a long tradition of election results disavowed by pragmatic political arrangements reflecting hard “international realities”.

Meloni has declared herself pro-EU and pro-Nato. The following months will reveal if and how she will be able to strictly honour such commitments.

https://www.middleeasteye.net/opinion/italy-elections-giorgia-meloni-political-earthquake-what-next

TheAltWorld

TheAltWorld

0 thoughts on “Giorgia Meloni: What comes next after Italy’s political earthquake?”