The UAE’s bitter choices: strikes in its cities or defeat in Yemen

There are two main choices for the UAE: escalate dramatically or exit quickly, both with considerable cost to Abu Dhabi

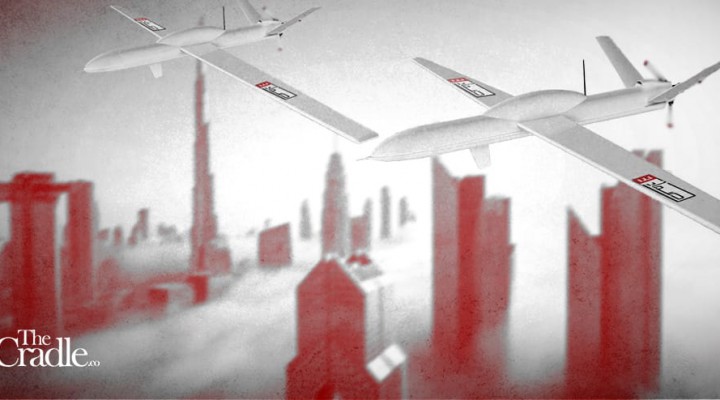

On 17 January, Yemeni resistance movement Ansarallah launched its first-ever retaliatory missile strikes into the UAE’s depth, hitting Abu Dhabi airport and a key petroleum facility. Within hours, the Saudi-led coalition struck Yemen’s capital, Sanaa, killing 23 civilians in the ensuing bombardments. Both sides have threatened to escalate, after seven years of a brutal war.

So, what are the options of the UAE and the Houthis after the recent and sudden military confrontations? Will Abu Dhabi withdraw again – as it claimed to have done in 2019 – or will it continue its expensive proxy war, via its Yemen-based mercenary armies? And how will the Houthis respond to each of these scenarios?

After the unprecedented drones and ballistic missile attack launched by Ansarallah, Yemen’s Houthi-dominated resistance movement, into the UAE’s territorial depth, there are two critical questions that arise. The first is about the real motives behind this new Ansarallah gambit, and the second, about the UAE’s reaction to this attack.

Importantly, will this escalation lead to a change in strategy in the long run: will Abu Dhabi return to this war after a semi-interruption of three years, or will it decide to withdraw completely this time – proxies included – in order to avoid potentially high costs?

The Houthis, who have targeted multiple strategic economic and military sites inside Saudi Arabia with ballistic and winged missiles over the past years, had thus far avoided targeting the UAE in its retaliatory strikes. The Emiratis are the second-lead and key partner in the Arab coalition’s “Decisive Storm” assault launched on Yemen by Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman in March 2015, in which he pledged to enter Houthi-controlled Sanaa “as a conqueror.”

When asked about why they neglected to retaliate against the UAE until now, sources close to the Houthis provided several reasons for that decision:

First, Ansarallah was unwilling to open two battle fronts at the same time – with Saudi Arabia and the UAE, both – in addition to their internal battlefronts with the UAE-backed Southern Transitional Council (STC), and the Saudi-backed Islah party and al-Sharia army.

Second, the Houthis had reached an implicit, unwritten agreement with the UAE that can be summed up thus: “We left the south to you, so leave the north to us, and do not interfere in it politically or militarily… and you will be safe.”

Third, the desire of Iran, an Ansarallah ally, to maintain a cautious balance with the UAE – especially with the Emirate of Dubai, a critical commercial gateway for undermining the severity of US sanctions on Iran, estimated to account for more than $14 billion annually in Emirati-Iranian trade.

Fourth, the sudden decision of the UAE in 2019 to withdraw its official troops gradually from Yemen after a sharp increase in soldier losses, estimated at 150 dead and hundreds more wounded.

Among the most prominent of those injured was Zayed bin Hamdan, the son of former foreign minister and governor of the northern region Sheikh Hamdan bin Zayed, and also the son-in-law of the the de facto ruler of the Emirates, Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi Mohammed bin Zayed (MbZ). Hamdan was paralyzed and is in a wheelchair.

The UAE’s strong return to the Yemeni theater in recent months, via its proxies, especially in the critical battles of Shabwah, Marib and Al-Bayda, has changed Ansarallah’s calculations. The UAE-backed Giant Brigades – headed by General Tariq Afash, nephew of the late Yemeni President Ali Abdullah Saleh – and other southern factions, upended all the equations on the ground when it stymied the advance of Ansarallah forces on these key frontlines.

Because of this Emirati escalation in recent weeks, Ansarallah lost partial control of the oil-rich Shabwah governorate, inflicting huge human losses in its ranks, tipping the scales toward the Saudi-backed Sharia army and easing the siege on them in Marib, which the Saudis were on the verge of losing.

After several days of hesitation, during which consultations took place with allies in Tehran, Beirut, and among Yemeni tribal leaders, Ansarallah decided to send a strong message to the UAE. It did so by bombing the Emirati depth, but in a reduced and deliberate way, to deliver a warning message to Abu Dhabi: “You breached the agreement.. If you go back, we will return, and he who warns have been excused (from explaining further),” say the Houthi sources mentioned above.

The Emirati military response came quickly, less than 24 hours later, with an aerial bombardment of the home of retired General Abdullah Qassem al-Junaid, head of the Yemeni Air College in the heart of Sanaa – where three families resided – killing about 23 civilians and wounding dozens for the first time in years.

There are two options for the UAE after these recent developments.

First, to revive the 2019 ‘truce agreement’ with the Houthis, which would entail ordering UAE proxies to immediately withdraw from the Shabwah, Marib and Al-Bayda fronts and return to their former bases on the western coast, south of Hodeidah and near Bab al-Mandab, as a first step.

Second, to advance its proxies into Ansarallah’s geographic red lines, and throw its full weight back into the Yemeni war to strengthen the exhausted military position of its Saudi ally. These were decisions implemented by the UAE and Saudi Arabia in an agreement reached during Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s (MbS) visit to Abu Dhabi before last December’s Gulf summit.

It is not known which of the two options the Emirati leadership will choose. The first will be difficult as it will require an exit from the Saudi-led war coalition, an increase in tension with Riyadh, and the abandonment of its allies’ military ambitions in southern Yemen – but it will lead to halting any new Houthi attacks in the Emirati depth.

The second option may be vastly more expensive, because the Houthis are likely to continue their bombing of the UAE with more powerful retaliatory strikes targeting the oil and tourism infrastructure, especially the airports and the facilities of the “ADNOC” company, an Emirati version of Saudi Aramco.

Ansarallah’s bombardment of the UAE with missiles and drones, although expected, constituted a dangerous new development. It changed all the rules of engagement and moved the Yemeni war to a new stage where developments are difficult to anticipate.

Israel is about 1,600 kilometers from Sanaa – approximately the same distance between Abu Dhabi and Yemen’s capital city. Tel Aviv’s assistance to the UAE to investigate the Ansarallah strike capabilities comes on the back of increasing Israeli fears that it could be the next destination for Houthi ballistic missiles and armed drones. So, how then could this new element influence the direction of the Arab coalition countries in this war, and the UAE, in particular?

This unprecedented bombing of the Emirati depth will either lead to accelerate the exploration of a solution to end the Yemeni war – or escalate it, expand its circle, and invite other regional parties into it. The new entrants could include the countries and arms of the resistance axis, jihadists from all over the world, Russia, China, and a more active presence by western NATO states – similar to what happened in Syria.

In all cases, the surprises of the new year have already arrived, faster than we could have imagined.

TheAltWorld

TheAltWorld

0 thoughts on “The UAE’s bitter choices: strikes in its cities or defeat in Yemen”