Myths of the Pandemic Deniers

Several western groups reacted to the COVID19 epidemic with startling myths, reflecting disbelief that their world could be shaken by something so trivial and random as a virus. Common to all was the idea that the new virus was not as dangerous as health agencies suggested, and that public health quarantine measures were totally unjustified. Defending individual liberties was their central theme.

Neoliberal government leaders, who stress liberty to defend a world of corporate privilege, denied the threat and delayed protective measures, until the weight of disease and death forced their hands. By that time they were presiding over the deepest of crises, in countries such as the USA, the UK, Brazil, Chile and Ecuador. These are corporate power brokers using ideas of ‘liberty’ and ‘choice’ to undermine and privatise public health institutions. Preventive health is at the core of public health systems but mostly ignored by curative private health. So neoliberal leaders typically resist substantial preventive measures. For example, US President Donald Trump played down the COVID19 problem for well over a month (AJ 2020; Brewster 2020) and, on the very day that the W.H.O. declared a global pandemic, suggested that the warmer weather in April could blow away the virus (Levin 2020). Similarly, UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson (before he himself was hospitalised with the virus) opposed “draconian measures”, including widespread testing or ‘track and trace’ measures. Johnson’s scientific adviser Patrick Vallance suggested that “probably about 60 percent” of people would need to be infected to achieve “herd immunity” (Yong 2020). But such ‘herd immunity’ is usually achieved by vaccines, not by general exposure to a deadly virus.

Right libertarians, particularly in the USA, simply opposed any form of quarantine, holding their individual freedoms above all public health concerns. Climate science deniers and right libertarians like Alex Jones, who regards the virus as a “hoax” were said to be in the “forefront” of pandemic denial (Holden 2020). Similarly ‘conservative’ commentators like Peter Hitchens stridently opposed quarantine measures, claiming that “the primary purpose of enforced muzzle wearing in public spaces (which protects nobody against anything) is to humiliate the wearer and make him or her accustomed to unquestioning obedience to authority” (Hichens 2020). The attack on liberties was called unjustified by a tenacious denial crowd. Australian right wing commentator Alan Jones called out the “dangerous virus theory” as “hysteria and alarmism”, in mid-March (Seidel 2020). He held to that line four months later, when deaths worldwide had risen to 600,000 (SkyNews 2020). Of course, none of these three were health specialists.

Similarly, a group of western populist liberals, applying a rejectionist logic, claimed conspiracy by states and powerful companies to deprive them of their freedom, and to forcibly submit them to harmful medications or vaccines. While most western liberals accepted quarantine rationales, whether because of their faith in state institutions, or for some other reason, the populist deniers were cynical, reacting against the idea of a pandemic and rejecting practical engagement with the common threat. They presented a denialist argument which, in its naïve arrogance, joined with the right libertarians and the neoliberals to trivialise the epidemic.

This group rejected public health rationales with a shallow anti-corporate critique. They accused pharmaceutical monopolies (Big Pharma) of a secret globalist agenda, claiming that states and the W.H.O. had already been captured by vaccine magnate Bill Gates and associates like top US health official Anthony Fauci (Bedo and Brown 2020; Bauder 2020; Marsh 2020). This was not a ‘left’ position as it used individualistic logic to reject preventive public health measures, asserting ‘my rights’ above all. It shared with the others a deeply anti-science bias, replacing systematic evidence with anecdotal accounts.

Pandemic deniers typically reject state data on COVID19 infections and deaths, claiming with naive certainty that the disease is ‘no worse than a seasonal flu’. Like the right libertarians they claim that face masks are useless: “[they] work well for surgeons who want to avoid dribbling or sneezing into their patients, but are useless when it comes to stopping viral infections … there is no evidence that they achieve anything at all” (Davis 2020). This claim simply ignored a series of scientific findings, outlined below in section 1.1.

All three groups fail to recognise the social, educative and preventive character of public health systems. Yet they differ in approach, particularly in how they see the role of the state. The neoliberals advance ‘liberties’ and ‘choice’ in health treatment, deferring to private curative medical services, until they are forced to address the competing demands on the state. Right libertarians also cry ‘freedom’, while relying on a strong state to defend property and privilege. Populist ‘woke’ liberals see virtue in opposing the state and the corporate media. Instead of an intelligent reading of the contradictions of the state, they pretend to reject it all, except when tabloid headlines suit their purpose.

The common myths reinforce a rejection of public and preventive health, ignoring the efforts of public health workers, reinforcing privatised-curative health systems and, in the case of the anti-vaccine campaigners, putting at risk the lives of millions, mostly children (see 1.5).

The deniers shared an autistic sensibility, oblivious to human suffering and the notion of common cause. Denying science on the pandemic – just like denying science on human induced global warming, or denying wars of aggression – only distracted and disqualified themselves from important public debates. First amongst these was how to manage the protective measures, for example to ensure that such measures are led by public health professionals and not relegated to para-military repressive measures. Similarly, they could not credibly engage in debates over the ways and means of improving social security, how to reopen and restructure economies and how to strengthen public health systems. Their myths deserve rebuttal. This paper will address five such myths, most of which are poorly articulated but ubiquitous on social media.

- The key myths

Pandemic denial claims are all over the corporate and social media but, due to their erratic character, there is little systematic literature to examine. I will characterise them without much referencing, leaving that for the rebuttals. I will also ignore some of the more marginal claims, such as attempts to link 5G technology to the virus, amateur debates over appropriate medication and claims that the virus is a deliberate attempt to reduce the world population.

The central myths are that (1) systematic health system evidence can be ignored, as evidence is simply an individual choice; (2) COVID19 is no worse than a seasonal flu or a common cold; (3) the ‘lockdown’ (strong quarantine measures) causes more deaths than the virus. The populist liberals add two more linked claims, that (4) the ‘lockdown’ is a US-based globalist conspiracy to lock everyone up and then forcible medicate us, and (5) vaccines are toxic, and part of the lockdown conspiracy.

1.1 Myth: systematic evidence can be ignored, evidence is an ‘individual choice’

Having discovered that there are uncertainties in contemporary epidemiological evidence, the pandemic deniers say this means all state and public health evidence is exaggerated and can be safely ignored. They proceed to replace social evidence with anecdotal evidence, as though that were somehow better. The typical assertion is that COVID19 deaths are exaggerated due to their conflation with deaths from other causes. At a time of uncertainty, one right wing columnist writes, all data is unreliable and “no one can accurately tally up unrecorded cases of COVID-19 and that single fact renders the modelling inaccurate. If the true fatality rate is closer to 1 per cent” then “locking down the world” would be “totally irrational” with potentially tremendous social and financial consequences may be totally irrational”. There was a need to “push back” against expert advice and government dictates (Albrechtsen 2020). Right libertarians and liberal populists basically agree on this.

Methodological weaknesses are at the root of this myth. The first is an asserted certainty, when public health science has been grappling with uncertainty. Somehow, based on some sort of supposed instinct or intuition, western amateurs say they know what damage the new virus causes and are sure it is relatively harmless. The unfolding of new evidence does not seem to influence this type of naïve arrogance, whether by the global death toll or from emerging evidence, months down the track, that this new virus affects not just respiratory systems but vascular and nervous systems (Criado 2020; Bleicher and Conrad 2020).

Second, instead of adjusting for the inevitable uncertainties in case of a new disease – as is the practice of all public health specialists – the pandemic deniers simply discard all health department evidence and, with a naive certainty, claim selected anecdotal opinions as a proper substitute. Where epidemiologists account for under-estimates as well as over-estimates, the pandemic deniers use a one sided logic which asserts that all death counts are overestimated. This illusory certainty, combined with adamant opposition to protective measures, means that the deniers effectively exclude themselves from meaningful discussions about how to manage the protective measures. What do they have to contribute, if they do not recognise the problem?

Third, this anti-science denialism is plagued by poor logic. A number of online accounts, for example, like to show correlations between ‘lockdown’ countries and high rates of infection. Suggesting a causal link in the desired direction, they show little understanding of the distinction between correlations and causes. Many do not seem to recognise that heavy quarantine measures (‘lockdowns’) may have come about after serious infections, nor that serious epidemics came after significant delays in imposing quarantine measures. In short, they mistake symptoms for causes, as I pointed out in a previous article (Anderson 2020).

Scientific evidence is simply ignored. On the question of the uses of face masks, for example, there are masses of assertions that there is “no evidence” that masks help prevent infection. That is just incorrect. While it is true that there is scientific debate over masking, it is not at all true to say that there is “no evidence” in support of masking as a defence against COVID19.

There was of course “no evidence” of any sort on the new virus until January 2020, when Chinese scientists identified it and published its genome (Cohen 2020). Since then, however, there have been a number of studies which range from cautious to strong support for mask wearing, especially as a supplemental means of virus control and especially in crowded areas. Let’s look at those studies at their source, not just through popular media accounts.

At the cautious end a New England Journal of Medicine report said that “universal masking alone is not a panacea. A mask will not protect providers caring for a patient with active Covid-19 if it’s not accompanied by meticulous hand hygiene, eye protection, gloves, and a gown” (Klompas, Morris, Sinclair, Pearson and Shenoy 2020). Two other cautious reports came from the University of East Anglia and CIDRAP. The East Anglia report said that “wearing facemasks can be very slightly protective against primary infection from casual community contact, and modestly protective against household infections when both infected and uninfected members wear facemasks” (Brainard, Jones, Lake, Hooper and Hunter 2020). The CIDRAP report, an assessment by an individual doctor, claimed there was “no evidence” masks were effective in COVID19 control, but accepted that “surgical masks likely have some utility as source control … from a symptomatic patient in a healthcare setting to stop the spread of large cough particles and limit the lateral dispersion of cough particles. They may also have very limited utility as source control or PPE in households” (Brosseau and Sietsema 2020).

Most other studies have been more positive. A Lancet article called masking “a useful and low-cost adjunct”. This paper addressed some “uncertainty”, in particular because “the WHO had not yet recommended mass use of masks for healthy individuals … [this was in part because] previous research on the use of masks in non-health-care settings had predominantly focused on the protection of the wearers and was related to influenza or influenza-like illness.” However this report concluded that “mass masking for source control is in our view a useful and low-cost adjunct to social distancing and hand hygiene during the COVID-19 pandemic” (Cheng, Lam and Leung 2020).

A British Royal Society study found that universal masking could help manage the pandemic and prevent a second wave of infections: “even when it is assumed that facemasks are only 50% effective at capturing exhaled virus inoculum … [even] home-made facemasks consisting of one facial tissue (inner layer on the face) and two kitchen paper towels as the outer layers achieved over 90% of the function of surgical mask … [nevertheless] a high proportion of the population would need to wear facemasks to achieve reasonable impact of the intervention … facemask use by the public, when used in combination with physical distancing or periods of lock-down, may provide an acceptable way of managing the COVID-19 pandemic and re-opening economic activity” (Stutt, Retkute, Bradley, Gilligan and Colvin 2020).

Another study in the American Thoracic Society found that masks could help as a preventive measure: “the mask can mitigate the current pandemic, as it may reduce coronavirus in aerosols and respiratory droplets … Although universal masking may seem tedious and is criticized by the lack of high-quality supporting evidence, we think it is reasonable to re-consider such a measure in all but sparse areas in the public” (Wong, Teoh, Leung, Wu, Yip, Wong and Hui 2020).

Yet another study showed that mask wearing was “associated with” lower mortality and that where “societal norms and government policies supporting mask-wearing by the public [this was] independently associated with lower per-capita mortality from COVID-19”. They concluded that “the use of masks in public is an important and readily modifiable public health measure” (Leffler, Ing, Lykins and Hogan 2020).

Similarly, a study published at the National Academy of Sciences found that face mask wearing was “the most effective means”, when combined with other measures, to prevent the spread of COVID19. The authors wrote: “the wearing of face masks in public corresponds to the most effective means to prevent inter-human transmission, and this inexpensive practice, in conjunction with extensive testing, quarantine, and contact tracking, poses the most probable fighting opportunity to stop the COVID-19 pandemic, prior to the development of a vaccine” (Zhang, Li; Zhang; Wang; and Molinae 2020).

Another review of evidence called mask wearing a low cost and effective intervention. “The preponderance of evidence indicates that mask wearing reduces the transmissibility per contact by reducing transmission of infected droplets in both laboratory and clinical contexts. Public mask wearing is most effective at stopping spread of the virus when compliance is high. The decreased transmissibility could substantially reduce the death toll and economic impact while the cost of the intervention is low” (Howard et al 2020).

The point of citing this catalogue of recent studies on face masks is not to advocate for universal masking. There can be no doubt that face masks are more appropriate in some circumstances than others. Similarly, imposed public health restrictions must remain proportionate to the threat (HRC 1999: 14). The point here is to demonstrate that those claiming that there is “no evidence” or no public health rationale for face masks, have joined in a campaign of disinformation. That campaign, whatever its motive, is fundamentally anti-science and counter to the preventive health values at the core of any decent public health system.

The pandemic deniers show little interest in emerging evidence on the actual disease (e.g. Wortham et al 2020) or on the uncertainties over whether any lasting immunity, or whether ‘natural herd immunity’ through mass infection or by vaccine, is even possible (McMillan 2020). This sort of naïve arrogance sees little need for systematic science.

1.2 Myth: COVID19 is ‘no worse than a seasonal flu’

The argument that the new virus was ‘no worse than a common cold or seasonal flu’ has been endlessly asserted, with a characteristic and ignorant over-confidence. The limited evidence brought to support this claim consists of opinions from occasional dissident medical workers. Much of this confident assertion came at a time when epidemiologists were still collecting evidence. A key reason pandemic deniers give for rejecting systematic data on death and illness is that deaths from some other reason or from some combination of illnesses (co-morbidity) are often wrongly cited as COVID19 deaths. Never mind that co-morbidity dangers apply to almost every other infectious disease. Official data is accused of general over-estimates, but not of under-estimates.

The weight of scientific studies by mid-2020 show the claim of ‘no worse than a common cold or seasonal flu’ to be quite false. Yet to demonstrate this we must review the measures used. The evidence on lethality of a disease uses two common measures: a case fatality rate (CFR) and an infection fatality rate (IFR). The CFR is a ratio which “measures the number of confirmed deaths among the number of confirmed cases of a particular disease at a given time”. CFRs are typically overstated in the early days of a new disease, as only those badly affected seek medical assistance. An IFR estimates the deaths as a proportion of the total number infected, including “asymptomatic and undiagnosed infections” (Shabir 2020). Estimating an IFR is difficult and relies on estimates and inference from groups which have been more thoroughly tested, such as those on cruise ships (Russell et al 2020). The US Center for Disease Control (CDC) in its May 2020 planning scenarios made estimates of between 20% and 50% undiagnosed cases, at that time (CDC 2020a).

Comparisons with the IFR for influenza are open to some doubt, partly because of limited past data and partly because some influenza outbreaks have been very serious. The only data we have from the deadly influenza epidemic of 1918-19, for example, are the records of mortality (Frost 1920: 584). In 2009 the estimated CFR for A/H1N1 influenza in England in 2009 was 0.026, and for those 65 years old or more 0.98% (Donaldson et al 2009). In the USA the H1N1 flu CFR in New York was estimated at between 0.54 and 0.86%, and for those 65 and over 0.94 to 1.5% (Hadler et al 2010). Estimating influenza IFRs is difficult, because that disease was generally not subject to mandatory reporting.

Early reported CFRs for COVID19 gave both over-estimates and under-estimates. Rates of 3% to 5% deaths initially came from some European countries. Only those very ill were presenting to hospitals (Damania 2020). An early paper in the British Medical Journal said that the first CFRs were likely overstated due to limited testing; the authors added that this matter “should not distract from the importance of aggressive, early mitigation to minimise spread of infection” (Niforatos, Melnick, and Faust 2020). Indeed, as testing widened, those CFRs were revised downwards. On the other hand, underestimates also came from amateur surveys which excluded the very ill. For example, the Bakersfield (California) clinic report from doctors Daniel Erickson and Artin Massihi suggested very low mortality (Shepard 2020). However this report systematically excluded more serious cases, which were referred to hospitals. Based on that biased survey Erickson and Massihi wrote that “COVID-19 is no worse than influenza, its death rates are low and we should all go back to work and school”. Yet infectious disease specialist Carl Bergstrom said Erickson and Massihi had used “methods that are ludicrous to get results that are completely implausible” (Ostrov 2020). This “reckless” report was condemned by the American College of Emergency Physicians as “inconsistent with current science and epidemiology regarding COVID-19” (ACEP 2020).

So, after several months, what credible evidence do we have on the actual danger of COVID19? In mid-June Dr Timothy Russell, a mathematical epidemiologist at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, said that “the studies I have any faith in are tending to converge around [a COVID19 IFR rate of] 0.5–1%” (Mallapaty 2020). In May 2020 Professor Anirban Basu estimated an COVID19 IFR in the USA of 1.3%, “substantially higher” than that for seasonal influenza “which is about 0.1%” (Basu 2020: 5). In May 2020 the US CDC (the federal agency charged with vigilance and preventive health) gave ‘five scenarios’ of possible COVID19 outcomes, for the USA. These gave “symptomatic case fatality ratios” (CFRs) ranging from 0.2% to 1% overall, and from 0.6% to 3.2% for those 65 and older (CDC 2020a). All of these scenarios were much higher than the suggested 0.1% IFR for the ‘seasonal flu’. A Canadian study in June showed an adjusted CFR of 1.6% for Canada and an adjusted CFR of 1.78% for the USA, as at 20-22 April (Abdollah et al 2020). An early study had estimated an “overall” IFR for China at 0·66% (0·39–1·33), “with an increasing profile with age” (Verity et al 2020). All that indicated a COVID19 IFR roughly ten times the IFR for the seasonal flu. And the character of the new virus was still under study.

Globally the evidence has been diverse. Writing in March Oke and Heneghan (2020) observed that CFRs “vary significantly, and over time” between countries, which creates “considerable uncertainty” over exact CFRs. However early cases did show that cardiovascular disease was highly “prevalent” amongst those who died from the virus. British epidemiologist Robert Verity said that early estimates “hovered around 0.9% – 9 deaths for every 1,000 people infected – with a broader range of 0.4 to 3.6% (Mallapaty 2020: 2). While higher figures were cited for different countries, several researchers provide IFR estimates of between 0.5% and 1%. Australian epidemiologist Gideon Meyerowitz-Katz stresses that substantial uncertainty remains (Mallapaty 2020: 4).

In late April Hendrie (2020) wrote that the CFR for the virus “sits within a hugely broad range around the globe”. That for Belgium was extraordinarily high, for example. Virologist Ian Mackay said differences in testing were “likely to be the key”. But the way deaths were reported also differed. While many say that COVID19 deaths are overestimated, having been conflated with those from other reasons, or from co-morbidities, Melbourne University epidemiologist Alan Lopez says official statistics have been “vastly underestimating” the true death toll, because of a likely hidden number of undiagnosed cases. He says co-morbidity and undiagnosed deaths are important, arguing for estimates based on excess deaths (Hendrie 2020).

The more serious impact on both older people and those with chronic diseases – especially cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, chronic lung disease, neurological disease, obesity and immune-suppression conditions (Wortham et al 2020: 5-6) – provides another reason for caution. There is said to be an eight fold risk of death “when moving from the 60-69 age group to the 70 and above range” (Sandefur et al 2020: 2). Co-morbidities – such as diabetes, hypertension and heart disease – “matter a lot”. They can scale COVID19 IFRs up, as well as down, for example one study calculates that “the probability from dying from a COVID19 infection for patients under 40 is roughly 134 times higher [if they have] a relevant co-morbidity” (Sandefur et al 2020: 3). That is, the new virus can seriously exploit chronic illness amongst younger people.

Developing countries have special vulnerabilities, often having a younger population but also higher morbidity amongst young people, combined with weak health system capacity. So “when high quality intensive care is lacking, the advantages of youth are more muted”. In low income countries “advantages” with respect to COVID19 IFRs “are likely to be partially offset by disadvantages in terms of the age distribution of comorbidities and even more so by gaps in health system capacity” (Sandefur et al 2020: 5-6).

In sum, the virus is certainly more dangerous than the average flu and still has some unknown features. Those claiming certainty to the contrary are fooling both themselves and others.

1.3 Myth: the ‘lockdown’ causes ‘more deaths than the virus’

With systematic evidence on death and illness ignored, all versions of the western pandemic deniers (neoliberal, right libertarian and liberal populists) allege that the negative effects of quarantine (such as depression, lack of medical care, domestic violence and suicides) outweigh any death or illness from the virus. If this were true it would be a serious matter; indeed it must be considered. However the deniers produce little more than assertions, rejecting quarantine and other preventive health measures. They typically do not complain about specific heavy handed measures, such as the inappropriate use of police powers. General opposition to ‘lockdown’ is often characterised by a categorical rejection of preventive health measures, based on individualistic logic.

So the British site OffGuardian asserts: “the lockdown will kill more people than the virus … we’re choosing between a mild to moderate disease and a devastating lockdown”. The article repeats, for emphasis: “The. Lockdown. Is. Killing. People.” (Knightly 2020). This is mostly a rhetorical onslaught. The British tabloid media made a greater effort to present evidence. So an early April media report in the Spectator and Daily Mail claimed that “150,000 Brits will die an ‘avoidable death’ during coronavirus pandemic through depression, domestic violence and suicides”. At that time about 9,000 were listed as having died in Britain from the virus. However no source or detailed rationale for the “150,000” predicted deaths was given for the claim (Chalmers 2020). Media references to what appeared to be the same report resurfaced in July, this time referring to “200,000 deaths” in Britain from the lockdown. However at paragraph 20 this Telegraph story cited the report as acknowledging there could be 500,000 COVID19 deaths “if the virus had been allowed to run through the population unchecked” (Knapton 2020). That meant more deaths from the virus.

A more serious criticism of quarantine regimes came in late July, with the heads of four U.N. agencies warning of the impact on child malnutrition. Children were suffering more from the ‘lockdown’ than from the disease, they said. The heads of UNICEF, the W.H.O., the F.A.O. and the World Food Programme issued a statement saying that “the COVID19 pandemic is undermining nutrition across the world … physical distancing, school closures, trade restrictions and country lockdowns are impacting food systems … [and] without timely action … 47 million children younger than 5 years [will be] affected by wasting”, most of them in Africa and South Asia (Fore, Dongyu, Beasley and Ghebreyesus 2020). Without discounting the need for sanitary measures against the pandemic they called for action to prevent child malnutrition, during the crisis, in particular to ensure:

- “Nutritious, safe and affordable diets” for all children

- “Investments … to improve maternal and child nutrition”

- “services for the early detection and treatment of child wasting”

- “Maintain the provision of nutritious and safe school meals”

- “Social protection to safeguard access to nutritious diets and essential services”

(Fore, Dongyu, Beasley and Ghebreyesus 2020).

Again, the British tabloid media misrepresented this report with one headline claiming ‘Coronavirus restrictions killing 10,000 children per month’ (Miler 2020). In fact the Lancet article said that might happen “without timely action” (Fore, Dongyu, Beasley and Ghebreyesus 2020). Of course, the W.H.O., a co-author of this report, had argued protective measures from the beginning.

Nevertheless, the UN statement draws attention to the importance of managing quarantine regimes, including the school and economic re-openings, rather than sterile debates over the virus versus the lockdown. It was known from early days that most vulnerable to this virus were older people and those with chronic illness, and that children would carry the virus into homes. The much censored Lebanese resistance leader Hassan Nasrallah decried the inhumanity of western individualists who argued against social protection, and for a type of ‘herd immunity’ through natural selection:

[Paraphrasing:] ‘Yeah, let these old people die, no problem, let’s leave them alone without care or support, so that the youth, who are the country’s future, workforce and economy, may survive.’ This is a descent in humanity. On the contrary, when humans get older, our human and ethical responsibility towards them becomes much bigger, even when it comes to your choice of words … So how could we abandon the elderly? Why? (Nasrallah 2020).

There have been a series of media reports on lockdown costs. In late May a CNN report (John 2020) posed the same question “is the damage caused by the lockdown worse than the virus itself?” that its political adversary President Trump had put two months earlier: “we can’t let the cure be worse than the problem itself” (Samuels and Klar 2020). The CNN report then addressed the question, with some recognition of the costs in unemployment and recession, and noting that Trump had claimed “You’re going to lose more people by putting a country into a massive recession or depression”. However CNN concluded this was a “false choice” and that economists had found the ‘more harm than good’ arguments to be “unconvincing” (John 2020).

The conservative UK Telegraph gave greater weight to the argument. Without minimising the devastation of the pandemic, the paper cited several substantial costs of the ‘lockdowns’, mostly to do with delayed healthcare: the risks of children dying of malaria, pneumonia or diarrhoea; many millions of babies at risk of diseases die to cancelled vaccination services; a “tsunami of mental health cases” and 1.6 billion children forced out of school (Rigby 2020). Substantial challenges, but no actual cost benefit accounting was attempted.

In July 2020 the same claim resurfaced: ‘lockdown may cost 200,000 lives, government report shows’. This story was said to be based on a government report from April and to have emerged in a more recent briefing by the UK Government’s Chief Scientific Advisor Patrick Vallance. Once again, the original report was neither linked nor published. Nevertheless, the UK Telegraph reported that more than 90% of the predicted 200,000 deaths were to come from “delayed healthcare” during the lockdown, and the rest from recession, suicide, domestic violence and accidents at home (Knapton 2020). The paper did provide some supporting detail: a forecast of 20 more domestic violence deaths in 2020; 500 more suicides; a deferral or cancelation of 75% of “elective care” over six months; a big fall in urgent referrals “in the early weeks of lockdown”; reports of delays in cancer diagnosis and treatment by the Institute of Cancer Research, which could lead to “4,700 extra deaths per year in England”; and “5,000 fewer heart attacks patients had attended hospital from March to May” (Knapton 2020).

There should be no doubt that delayed healthcare, particularly in urgent cases, is a real cost of severe quarantine measures, a critical issue which must be addressed by health systems. Yet quantifying such risks requires systematic analysis and (at the time of writing) we do not have the actual report. On the other side the Telegraph acknowledged that the official report had suggested 200-500 fewer deaths from “road traffic and air pollution”, 67 fewer murders and an estimate of 500,000 COVID19 deaths “if the virus had been allowed to run through the population unchecked” (Knapton 2020). On balance, then, this unpublished report was said to suggest more than double the deaths with ‘lockdown’ than without, contradicting the ‘more harm than good’ headline.

So what about the published, systematic studies on the important question of the costs of quarantine? These seem to fall into two broad groups: comparative mortality, mostly through delayed healthcare and economic cost-benefit analyses.

On the question of delayed healthcare due to COVID19 restrictions, Dr Renata Thronson prepared a report for the Journal of the American Medical Association in which she recognised that (in highly privatised health systems like that of the USA) the pandemic and the restrictions caused many to lose their work-linked health insurance, while many also avoided treatment out of fear of exposing themselves to infection at the healthcare site. Emergency visits were said to have declined 42% in the USA and a majority (60%) of doctors believe that patients will experience “avoidable illness” due to delayed or avoided care (Thronson 2020; Definitive Healthcare 2020). Problems are identified but no final accounting ledger of predicted deaths is presented.

A Swiss study of the “psychosocial consequences of COVID19 mitigation strategies” used measures of ‘years of lost life’ (YLL) and tried to account for a range of factors: suicide, depression, alcohol use disorder, marriage stress and breakdown, childhood trauma and social isolation. They calculated that Switzerland “the average person would suffer 0.205 YLL due to psychosocial consequence of COVID-19 mitigation measures”, yet this burden would fall “entirely” on the shoulders of 2.1%, who would suffer an average 9.79 YLL (Moser, Glaus; Frangou and Schechter 2020). They are speaking of vulnerable groups, the elderly and those with chronic illness.

The economic analyses begin with estimates of comparative death and move into dollar values. In early May economists Neil Bailey and Daniel West tried to estimate the cost in lives of the COVID19 ‘lockdown’ in Australia (less severe ‘lockdowns’ than those of Wuhan and Hubei), calculating the likely extra suicides plus deaths “associated with loneliness from a lock down of six months” and some other lockdown caused deaths e.g. from alcohol abuse. They used three different regimes (1) normal plus targeted quarantine, (2) an easing to allow for ‘herd immunity’ through mass infection, and (3) the maintenance of restrictions until the virus is contained, followed by extensive tracking and tracing aimed at eliminating the virus”. They came down in favour of (3), saying that “when it comes to human lives, far fewer will be lost by continuing restrictions than would be lost by ending them now” (Bailey 2020). Similarly, a study on the economic costs of lockdown in the US and EU concluded that the likely hospitalization costs of mass infection were massive. So while “the economic costs of the great lockdown, while very high, might still be lower than the medical costs that an unchecked spread of the virus would have caused” (Gros 2020: 7).

Putting a financial value on human life (US$10 million in the USA, A$4.9 million in Australia), economists Richard Holden and Bruce Preston calculated an unprotected loss of life in Australia (at IFR=1%) of 225,000 deaths and therefore a loss of A$1.1 trillion, compared to an estimated A$180 billion cost (-10% GDP) of the Australian lockdown. On that basis they concluded that the costs of the ‘shutdown’ were “outweighed by its benefits” (Holden and Preston 2020).

On the other side of that economic debate, economist Gigi Foster, working with ‘value of a statistical life’ (VSL) measures, suggested that “Australia’s lockdown was a mistake” (Foster 2020). In the UK economist David Miles, using ‘quality adjusted life years’ (QALYs) and looking at the “future damage of huge disruption to education”, suggested that “extending the UK lockdown beyond three-months was not likely to be optimal (Miles 2020). Similarly, a British banking group warned of the mounting costs of the lockdown (Lea 2020) while a conservative economist suggested that the costs of lockdown “could far outweigh the benefits” (Ormerod 2020).

In a similar vein, in what was said to be the first peer-reviewed study to comprehensively assess potential global supply chain effects of COVID19 lockdowns, a group of economists modelled the impact of lockdowns on 140 countries, including those not directly affected by COVID19. This paper looked at productivity losses, used three types of lockdown (strict, moderate and lighter) and drew attention to the greater damage in extended lockdowns. It concluded that “losses are more sensitive to the duration of a lockdown than its strictness. However, a longer containment that can eradicate the disease imposes a smaller loss than shorter ones. Earlier, stricter and shorter lockdowns can minimize overall losses” (Guan et al 2020). That is, the equation was likely to change with longer lockdowns.

The cost of delays in imposing the US lockdown have also been modelled, at Columbia University. The estimate of that study in infectious disease modelling, published in mid-May, was that if quarantine measures had been imposed two weeks earlier, about 54,000 fewer deaths would have occurred (Glanz and Robinson 2020). Those delays can be likened to the failure to contain a forest fire in its early stages, a failure which leads to a much wider blaze, far more difficult to control.

As it happened, many of the quarantine regimes did relax, after two to four months duration. Not that this mattered much to many populists, who maintained that even after easing “we are very much still under lockdown” (Knightly 2020). Nevertheless, after three and a half months the British Office of National Statistics carried out a mid-July survey which showed that a great majority (93%) of British adults were leaving their homes, more than half (61%) were wearing face masks in public, about half (55%) said they were maintaining some form of “social distancing” and half (50%) of those over seventy years old were having visitors at their homes (ONS 2020). How that relaxation fares in a possible ‘second wave’ of infections remains to be seen.

While there are many conservative and populist assertions and some economic and media assessments which argue that the costs have been great, or too great, overall the systematic studies favour the quarantine measures, so long as they (a) are as targeted as possible and (b) observe some proportionate and finite limits.

1.4 Myth: the lockdown is a ‘conspiracy’ to lock us all up

This argument comes from both right libertarian and populist liberals. They say the restricted measures are not only unjustified but that have been put in place to benefit either an inexorably repressive state or a cabal of private companies, such as a Bill Gates-led vaccine industry. Conservatives have claimed that “the primary purpose of enforced muzzle wearing … [is to promote] unquestioning obedience to authority” (Hichens 2020); while populists point to shadowy links between “philanthro-capitalism, Big Pharma and government agencies, all effectively working in lock-step to promote the global immunisation agenda, with massive projected profit for the Big Pharma complex and in particular for the members closely associated with Gates, the WHO, UNICEF, and world governments” (Beeley 2020). The populist conspiracy theory, despite its rhetoric against Big Pharma, is not a left argument. The method is individualistic and it centres on a rejection of preventive health. In substance such populists misread the behaviour of oligarchies, mistaking symptoms of the crisis for its causes.

Now while it is certainly true that the big drug companies will try to exploit any crisis to make money, and that the US system is geared up to subsidise that process (Lerner 2020), the US Government was clearly wrong footed by this pandemic and has not (to its frustration) been driving the pandemic agenda. Those alleging a lockdown conspiracy fail to see that the leaders of the US and UK delayed quarantine measures for weeks and, as a result, ended up being forced to act in the face of mass infection and death. Most economies incurred massive economic losses and the US is a long way from the lead in vaccine development. Table 1 below provides an overview of the reasons against a globalist lockdown conspiracy. Further explanation follows.

| Table 1: How we know the ‘lockdown’ is NOT a globalist conspiracy | |

| 1. | Key neoliberals leaders (e.g. Trump) resisted quarantine for many weeks, before technocrats pressured them into it; only after that they applied repressive measures. |

| 2. | Big Pharma revenue is about 1% of total revenue lost by the global lockdown; the corporate world did not want a shutdown in production. |

| 3. | Vaccines are about 3.5% of Big Pharma medicine revenue; those companies make far more money from treatments than from vaccines. |

| 4. | The four leading COVID19 vaccine candidates (at July 2020) were three from China and one from Britain, all are backed by promises of non-profit production. |

| 5. | Notions of a US-based globalist conspiracy to impose ‘lockdowns’ ignores the public health measures of independent countries e.g. north Korea, Cuba, Syria. |

The absurdity of the conspiracy claim should have been obvious. First of all, corporate capitalism needs a free moving and complaint workforce, to generate profits. Most corporations did not want any sort of lockdown and, after it was imposed, they want to be rid of it as soon as possible, to restore production. The corporate media, particularly the financial media, is full of this argument.

The epidemics in each country caught neoliberal leaders like Donald Trump and Boris Johnson by surprise. They did not act out any repressive plan in the early months, and only resorted to ‘lockdown’ measures when the logic of events overtook them. They flip-flopped from talking down the problem and doing nothing, then reverting to heavy handed police measures.

The logic behind the shift from ‘do nothing’ to repressive measures came from the neoliberal instinct to leave health issues to ‘market forces’, that is, at the mercy of giant corporations. Then individual ‘consumer choice’, based on user pays systems, would regulate health care. The western populist ‘anti lockdown’ crowd seemed to not recognise how close their rhetoric was to that of Donald Trump.

After the ‘do nothing’ phase, the epidemic took off in neoliberal countries, with infection and death tolls mounting. That was noted by technocrats, who pressured the neoliberal leaders to impose protective measures, in particular quarantine and other sanitary requirements.

Using the USA as an example we can see this tension within the neoliberal state. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is one of the few elements of a US public health system. It collates information from states and territories and can advise on prevention campaigns. Through its National Center for Health Statistics the CDC publishes extensive information on how data is revised, not least on how COVID19 deaths are reported and collated (NCHS 2020). The populist deniers saw its compromised public-private links and naively decided that it was part of the corporate conspiracy. They missed some important tensions.

From the first weeks of the epidemic in the USA there were ‘mixed messages’ from the CDC and the Trump administration, in particular over the need for protective measures (Lutz 2020; Shear 2020). Then in April the CDC Director distanced himself from Trump’s criticism of the W.H.O. (Joseph 2020). In May Trump was said to have ‘sidelined’ the CDC in his urge to reopen the US economy (W. Roberts 2020). By July Trump had pushed the CDC out of its role to collate and publish data on the epidemic (Stolberg 2020) and was attacking CDC scientists on how to safely reopen schools (Murphy and Stein 2020). In the meantime Trump withdrew US funding from the W.H.O., enraged at its public health advice and apparently pro-China position (Chappell 2020). Both the W.H.O. and the CDC had important differences with Washington’s economic managers.

Second, there was negligible economic incentive for any lockdown which would shut down entire economies. The pandemic deniers suggested that, because there are government-corporate links between health systems and drug companies, especially in neoliberal states like the US and the UK, the ‘lockdown’ was therefore driven by a plan to frighten and medicate us all (e.g. Beeley 2020 Alba 2020). That claim bears little relation to the realities of the privatised health industry, let alone the wider economy.

The pandemic and protective responses catalysed a huge crisis, in reality multiple crises in health, social security, finance and economy. In June 2020 the IMF conservatively estimated negative global growth of minus 4.9% for 2020 (IMF 2020), and worse in the wealthy countries, meaning at least a 5% fall in the global output of 86 trillion dollars (World Bank 2020: using 2018 data). A preliminary gross economic loss estimate of the pandemic (without counting more than half million lives lost) was at least 4.3 trillion dollars. That was far more than the few billion thought to be gained in profit from the sale of vaccines. Not even the most predatory capitalist state represents just one fraction of the corporate world.

Third, while there can be no doubt that Big Pharma seeks to exploit the crisis, vaccines represent a small fraction of their revenue stream and profits. Vaccine revenue of around 35 billion is likely less than 3.5% of the total pharmaceutical revenue of around US$1 trillion (Evaluate Pharma 2017), highlighting the fact that curative drugs are far more lucrative than immunity inducing vaccines. There are only two vaccines in Big Pharma’s top 50 revenue earning medications, the vaccines for pneumonia and HPV (Evaluate Pharma 2017: 36-37).

Drawing on the estimated (and high) median profit margins in Big Pharma – and there is no reason to believe that vaccine profit margins are higher than those of other pharmaceuticals – of 13.8% (Ledley, McCoy and Vaughan 2020; see also Slovak 2018), the total annual Big Pharma profits on vaccines might amount to as much as US$4.87 billion in 2022. That is not much more than one thousandth part of the general economic losses during this crisis.

| Table 2: Vaccine revenue is a small part of Big Pharma Revenue | ||

| 2017 | 2022 | |

| Total drug revenue | 774 USD bn | 1060 USD bn |

| Total vaccine revenue | 27.5 USD bn | 35.3 USD bn |

| Vaccine revenue as % total drug sales | 3.55% | 3.3% |

| Profit on vaccine sales (@13.8%) * | 3.80 USD bn | 4.87 USD bn |

| Sources: Evaluate Pharma 2017: 8, 31, 36-37; and * Ledley, McCoy and Vaughan 2020 | ||

One analyst reasonably concludes that Big Pharma could reap far more revenue and profit from the ongoing treatment of diseases than through vaccine sales (Skeptical Raptor 2019). And that is assuming there will be any bonanza at all in vaccine sales.

This brings us to lockdown conspiracy myth-busting reason number four: notwithstanding the ambitions of big American and European drug companies, there has always been considerable uncertainty over whether there will be any ‘pot of gold’ at the end of the pandemic ‘rainbow’. Contrary to the globalist assumption that the USA runs the world, the leading US COVID19 vaccine candidate, that produced by Moderna (NIH 2020), is running behind four other candidates, three from China (Sinovac, the Wuhan Institute/Sinopharm and the Beijing Institute/Sinopharm) and one from Britain (the Oxford/AstraZeneca partnership), all of which had entered their final phase three trials by July 2020 (Butantan 2020; Chen 2020; O’Reilly 2020; W.H.O. 2020).

All four leading vaccine candidates are subject to political promises that they will be provided, during the pandemic, on a not for profit basis. The strongest promise comes from Chinese President Xi Jinping, who in May said: “COVID-19 vaccine development and deployment in China, when available, will be made a global public good. This will be China’s contribution to ensuring vaccine accessibility and affordability in developing countries” (Wheaton 2020). A similar commitment was linked to the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine project, even though it is a public-private partnership, with reports that: “The Company is seeking to expand manufacturing capacity further and is open to collaborating with other companies in order to meet its commitment to support access to the vaccine at no profit during the pandemic” (University of Oxford 2020). The odds therefore seem against the pandemic leading to a vaccine bonanza for US drug companies. However that still leaves open the field of drugs for COVID19 treatment.

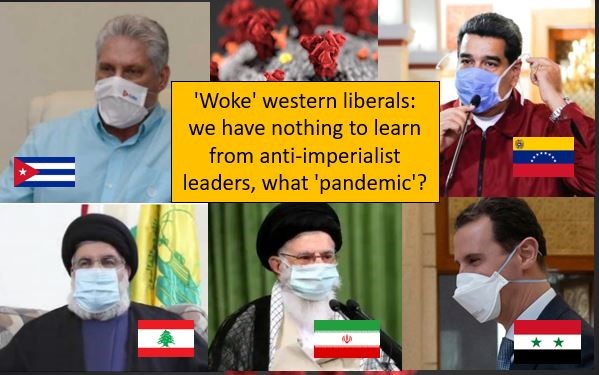

The fifth and final reason against a ‘lockdown conspiracy’ is that a number of independent countries – without the remotest link to the alleged Gates-Fauci-W.H.O. cabal – adopted quarantine measures even more rapidly than those of the US and UK. Once again, globalist assumptions mislead the pandemic deniers. Even a brief review of the responses of countries specifically cut off from the US-EU oligarchy, such as north Korea, Cuba, Syria, Iran and Venezuela, would have detected strong quarantine measures in all countries. Reading the experience of other countries always helps us understand international phenomena.

1.5 Myth: Vaccines are a ‘toxic’ part of the lockdown conspiracy

A second leg of the ‘lockdown conspiracy’ myth has been that this conspiracy includes a plan to forcibly medicate us all with toxic vaccines (Alba 2020). In this respect the pandemic deniers mostly adopt the stories of a pre-existing anti-vaccine campaign, which has gained some ground amongst western liberals in recent decades (Cassella 2019). The argument here is that all or most vaccines are dangerous and have, amongst other things, caused autism in children. In the COVID19 pandemic the argument is that the severe reaction to the epidemic gives either the state or Big Pharma a chance to make vaccination mandatory.

In the previous section the argument that vaccines provided a commercial rationale for the lockdown was discounted. Big pharmaceutical companies make far more money from drugs which treat disease than by vaccines, which stimulate immune systems to create anti-bodies. This section will address the claim that vaccines are dangerous, then present evidence on the benefits of vaccines and address the concern about mandatory vaccines.

The western populist liberal campaign against vaccines sometimes speaks of particular vaccines or particular vaccine owners, but it mostly fuels a general fear and rejection of all vaccines, reverting to liberal ‘individual choice’ arguments above considerations of public health. One commentator says, of what he calls an anti-vaccine “religion”, that they maintain “beliefs that vaccines cause autism, that HPV vaccines are dangerous, or that vaccines contain a dangerous amount of aluminium. These faith-based myths have been shown to be demonstrably false, again and again” (Skeptical Raptor 2018). Nevertheless, the anti-vaccine campaign seemed to gain a boost in 1998 when the former British doctor Andrew Wakefield published a paper in The Lancet alleging a proven link between the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine and autism in children. Very quickly MMR vaccination rates “began to drop because parents were concerned about the risk of autism after vaccination” (Sathyanarayana Rao, and Andrade 2011).

However Wakefield’s data was found to have been fabricated. The General Medical Council of Britain struck him off the register of doctors in 2010, after this fraud was exposed. The former doctor, who portrays himself a victim of Britain’s medical establishment, was found guilty of “offences relating to dishonesty and failing to act in the best interests of vulnerable child patients” (Boseley 2010). In a rare act the Lancet editors retracted the paper (Offitt 2010). Many subsequent studies have found no link between the MMR vaccine and autism. Citing several subsequent studies (e.g. DeStefano, Price and Weintraub 2013), the US CDC has repeatedly stated that ‘there is no link between vaccines and autism’ (CDC 2020b). The finding of “no increased risk for autism after MMR vaccination” has been replicated in other countries, such as Denmark (Hviid, Hansen; Frisch and Melbye 2019).

Linked claims from the anti-vaccine campaigners include allegations that toxic substances (mercury, aluminium, offal, viruses) are placed in vaccines, for unexplained reasons. Regarding mercury there is a ‘true but meaningless’ link with the preservative thimerosal. This substance (containing ethyl mercury) was used until about 2001 as a preservative in some vaccines. However several studies have demonstrated, first, no harm from the quantities of thimerosal which were used (less ethyl mercury than the more toxic methyl mercury which can be found in a small can of tuna); and second, after 2001, on precautionary grounds and following public concern, “thimerosal was removed or reduced to trace amounts in all childhood vaccines except for some flu vaccines” (CDC 2013; CDC 2020b). More than a decade back there were “twenty epidemiologic studies have shown that neither thimerosal nor MMR vaccine causes autism” (Gerber and Offit 2009). The basis for the mercury scare was like saying multivitamin pills contain cyanide, which indeed they do but in insignificant amounts, via the compound for Vitamin B12. Many other countries assume responsibility for checking that their medicines, including vaccines, are safe.

Vaccines, unlike curative drugs, form part of preventive health. They are more economical and their occasional use poses fewer risks than ongoing medication. It is well established that the persistent use of curative drugs (many powerful treatment drugs are prescribed to be taken over many years) increases the risk of many positively identified ‘side effects’. That is far less the case with one off or occasional vaccines. Vaccines do have side effects, but serious effects, like allergic reactions, are estimated to be very low, perhaps one or two per million (HHS 2020).

Vaccines have brought about dramatic improvements in human health and so are adopted by virtually all public health authorities. Smallpox, caused by the variola virus, killed literally hundreds of millions. It is the only human disease to have been completely eradicated and this happened by a one-time vaccine (Bradford 2019; Henderson and Klepac 2013). Polio is a paralytic disease which can have severe effects on children, It is caused by three types of virus, but they have been controlled by two types of vaccine, one using an active (OPV) and the other an inactive (IPV) vaccine. There were some risks of resurgence with the active vaccine (OPV), but these are being removed by a general reversion to the inactive version (Baicus 2012). In the year 2000 there were 30 million to 40 million cases of measles, which caused 777,000 deaths, or “nearly half of the 1.7 million annual deaths due to childhood vaccine-preventable diseases”. The measles vaccine, typically combined with that for Mumps and Rubella (the MMR vaccine combination) has drastically reduced death and illness from this disease. The WHO and UNICEF say that “failure to deliver at least one dose of measles vaccine to all infants remains the primary reason for high measles morbidity and mortality” (WHO-UNICEF 2002).

Vaccines have been and remain as great life savers, to help prevent rather than treat many illnesses. Britain’s NHS says that “vaccination is the most important thing we can do to protect ourselves and our children against ill health. They prevent up to 3 million deaths worldwide every year” (NHS 2020). The World Health Organization says that: “vaccines prevented at least 10 million deaths between 2010 and 2015, and many millions more lives were protected from illness.” They are referring to success stories in preventing pneumonia, diarrhoea, whooping cough, measles, and polio, mostly in children (WHO 2017).

Yet undermining public confidence in vaccines, with false scare stories like the false MMR-autism claims, has put children’s lives at risk. Typically vaccination has not been mandatory for adults (except for international travellers) but has relied on a very high voluntary uptake. In 2018, 140,000 died from measles, “overwhelmingly children under 5 years of age” (WHO 2019) Unfortunately scares around vaccines have undermined public confidence in some countries. For example in Samoa, after a dramatic fall in the levels of child MMR vaccination (following two deaths which followed medical malpractice), there was an outbreak of measles in which 72 people died, mostly children. That led to an introduction of mandatory MMR vaccination in Samoa, in late 2019 (Gibney 2019; Isaacs 2020). More recently, vaccination campaigns have been stopped in countries like the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) due disruptions caused by the COVID19 crisis (L. Roberts 2020).

Yet when it comes to COVID19 there is reason to believe that immunity from the emerging vaccines may not last long (McMillan 2020), and that might mean repeated treatments, like the influenza vaccines, perhaps once a year. Even in this circumstance, it has been shown that it is more economical (and drug companies gain less revenue) from once per year vaccinations than they would from drugs used to treat sick patients. Régnier and Huels (2013) concluded that “manufacturers may see higher incentives to invest in curative treatments rather than in routine vaccines”. This reinforces the point that big drug companies, and highly privatised health systems, have less to gain from vaccines than from curative medicines.

The anti-vaccine campaigners have tried to turn the public health argument into an individual liberties argument (‘my body, my choice’), to argue that vaccines should not be mandatory. Like the face mask debate, this seeks to turn the concerns of social responsibility and preventive health into simple matters of individual choice. Naturally that acts to undermine public health systems, founded as they are on health education and preventive measures. In fact (except for public health workers and international travellers) vaccines have generally not been compulsory for adults. Nevertheless, many countries have already introduced mandatory testing (and the requirement of a negative test) for COVID19, as a condition for the entry of international travellers. This is distinct from the responsibility to receive and look after their own citizens, regardless of illness. In the 1960s and 1970s there were requirements for mandatory smallpox vaccination, for most international travellers. There can be no doubt that states are entitled to use such measures, to protect their own populations from the risk of imported infection.

- In conclusion

The three mostly western groups described here – neoliberals, right libertarians and populist liberals – share much in their efforts to create myths which confuse the public over universal public health measures. These have been adopted in most countries, including many quite independent from the US corporate world. These myths distract from many necessary and practical debates during the pandemic crisis: how to actually manage the protective measures, how to improve social security, how to reopen and restructure economies and how to strengthen public health systems.

The naïve arrogance of the myth builders projects a certainty not shared by scientific study of the new virus. Substituting select anecdotal evidence for systematic evidence, many pandemic deniers berate people to ‘wake up’ to the ‘truth’ they discovered long ago, unburdened by recourse to any emerging evidence on the virus or on human morbidity and mortality.

Their myths can be characterised in five main themes. First, there is a naïve certainty in beliefs which have little scientific foundation. They reject systematic evidence on the disease. Because contemporary official data carries uncertainties, that is considered good enough reason to reject it all, putting in its place selected anecdotes and opinions.

Second, the COVID19 virus is repeatedly said to be ‘no worse than a common flu’, when most epidemiologists place it as about ten times more dangerous, and with new features beyond a simple respiratory disease. ‘Death from other causes’ is chanted as a means of denying death counts across multiple countries, without recognising that co-morbidity applies to virtually all serious disease, including influenza.

Third, sections of the corporate media, right libertarians and western populists alike claim that ‘the lockdown cause more deaths than the disease’, without ever presenting substantial evidence to back up this claim. The damage caused by quarantine measures is real enough – notably delayed health care (including delayed vaccination programs and treatment of chronic illness) and child nutrition – but these problems must be assessed in a rational way.

The ‘lockdown is the problem’ idea masks the failures of highly privatised, neoliberal health systems to protect their own populations (Anderson 2020). A ‘lockdown’ was neither planned nor wanted by western oligarchies, led by giant corporations. To the contrary, it hurt their capacity to exploit labour and the environment and so generate profits. Key neoliberal representatives such as Donald Trump and Boris Johnson maintained the liberal line as long as they could. Their delay in imposing protective measures led to deeper and longer lasting epidemics than in many other countries. Their delayed, clumsy reactions led to repression and so generated further resentment. Pandemic deniers missed this, confusing symptoms of the crisis for its causes.

Fourth, many libertarians and populists claimed a conspiracy to lock us all up as part of a totalitarian plan, sometimes said to be for the commercial advantage of a corporate drug industry. This theory ignored the opposition to economic shutdowns by much of the corporate sector, the minimal and fragile expectations of profit from any new vaccines and the adoption of similar quarantine measures across a range of quite independent countries. Further, the populist claim effectively supports a corporate driven neoliberalism which rejects public health systems in favour of individual choice in private health treatment. The social character of public health values and public health systems, including preventive measures which barely exist in privatised health systems, was lost in the liberal obsession with individual choice.

Finally, the pandemic denial myths often adopt the pseudo-science of anti-vaccine campaigns, which have a longer history. Even though there is not yet any proven COVID19 vaccine (though dozens are in development), the very possibility of a vaccine is said to be part of a conspiracy against public health. That claim draws on comprehensively disproven claims made against several life-saving vaccines, including those for measles and polio. For some peculiar reason, harmless vaccines have attracted more fear and suspicion than the far more profitable treatment drugs, many of which must be taken continuously, raising the likely incidence of harmful side-effects.

The character of pandemic denial is rooted in an anti-social western individualism, which rejects preventive health measures and effectively undermines public health systems, in favour of the privatised models. Yet these are the very systems which failed so badly in the current crisis. Through their absolutism the libertarian and populist pandemic deniers effectively disqualified themselves from engagement in the important debates over management of quarantine measures, social security and economic restructuring. The myths of this crisis acted to negate the demand for stronger public health systems. Those myths should be more fully discussed if there are to be advances in public health.

https://ahtribune.com/world/covid-19/4331-pandemic-deniers.html

—————-

References

ACEP (2020) ‘ACEP-AAEM Joint Statement on Physician Misinformation’, American College of Emergency Physicians, 27 April, online: https://www.acep.org/corona/covid-19-alert/covid-19-articles/acep-aaem-joint-statement-on-physician-misinformation/

Adrian, Tobias and Fabio Natalucci (2020) ‘Financial Conditions Have Eased, but Insolvencies Loom Large’, 25 June, online: https://blogs.imf.org/2020/06/25/financial-conditions-have-eased-but-insolvencies-loom-large/

AJ (2020) ‘A timeline of the Trump administration’s coronavirus actions’, Al Jazeera, 24 April, online: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/04/timeline-trump-administration-coronavirus-actions-200414131306831.html

Alba, Davey (2020) ‘Virus Conspiracists Elevate a New Champion’, New York Times, 9 May, online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/09/technology/plandemic-judy-mikovitz-coronavirus-disinformation.html

Albrechtsen, Janet (2020) ‘Coronavirus: It’s time for us to decide if the cure is worse than the disease’, The Australian, 27 March, online: https://www.theaustralian.com.au/inquirer/coronavirus-its-time-for-us-to-decide-if-the-cure-is-worse-than-the-disease/

Anderson, Tim (2020) ‘How the Pandemic Defrocked Hegemonic Neoliberalism’, American Herald Tribune, 22 May, online: https://ahtribune.com/world/covid-19/4181-pandemic-defrocked-hegemonic-neoliberalism.html

Baicus, Anda (2012) ‘History of polio vaccination’, NCBI, World J Virol. 12 Aug; 1(4): 108–114, online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3782271/

Bailey, Neil (2020) ‘The calculus of death shows the COVID-19 lockdown is clearly worth the cost’, MedicalXPress, 8 May, online: https://medicalxpress.com/news/2020-05-calculus-death-covid-lockdown-worth.html

Basu, Anirban (2020) ‘Estimating The Infection Fatality Rate Among Symptomatic COVID19 Cases In The United States’, Health Affairs, 7 May, online: https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00455

Bauder, David (2020) ‘Sinclair pulls show where Fauci conspiracy theory is aired’, PBS, 10 May, online: https://www.pbs.org/newshour/science/sinclair-pulls-show-where-fauci-conspiracy-theory-is-aired

BBC (2020) ‘Coronavirus: Trump stands by China lab origin theory for virus’, 1 May, online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-52496098

Bedo, Stephanie and Natalie Brown (2020) ‘’We don’t consent’: Dramatic scenes at anti-lockdown protest’, Daily Mercury, 10 May, online: https://www.dailymercury.com.au/news/we-dont-consent-dramatic-scenes-anti-lockdown-prot/4012592/

Beeley, Vanessa (2020) ‘COVID-19: the Big Pharma players behind UK Government lockdown’, UK Column, 6 May, online: https://www.ukcolumn.org/article/covid–19-big-pharma-players-behind-uk-government-lockdown

Bleicher, Ariel and Katherine Conrad (2020) ‘We Thought It Was Just a Respiratory Virus’, UCSF, Summer, online: https://www.ucsf.edu/magazine/covid-body

Boseley, Sarah (2010) ‘Andrew Wakefield struck off register by General Medical Council’, The Guardian, 25 May, online: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2010/may/24/andrew-wakefield-struck-off-gmc

Bradford, Alina (2019) ‘Smallpox: The World’s First Eradicated Disease’, Live Science, 23 April 23, online: https://www.livescience.com/65304-smallpox.html

Brainard, Julii; Natalia Jones, Iain Lake, Lee Hooper, Paul R Hunter (2020) ‘Facemasks and similar barriers to prevent respiratory illness such as COVID-19: A rapid systematic review’, MEDRXIV, 6 April, online: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.01.20049528v1.full.pdf

Brewster, Jack (2020) ‘Fauci Says It’s ‘False’ To Say The Coronavirus Outbreak Is Under Control; Here Are All The Times Trump Said It Was’, Forbes, 5 April, online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/jackbrewster/2020/04/05/fauci-says-its-false-to-say-the-coronavirus-outbreak-is-under-control-here-are-all-the-times-trump-said-it-was/

Brosseau, Lisa M and Margaret Sietsema (2020) ‘COMMENTARY: Masks-for-all for COVID-19 not based on sound data’, CIDRAP, 1 April, online: https://www.cidrap.umn.edu/news-perspective/2020/04/commentary-masks-all-covid-19-not-based-sound-data

Butantan (2020) ‘Clinical Trial of Efficacy and Safety of Sinovac’s Adsorbed COVID-19 (Inactivated) Vaccine in Healthcare Professionals (PROFISCOV)’, Clinical Trials, 2 July, online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04456595?term=vaccine&cond=covid-19&draw=2&rank=1

Cassella (2019) ‘Robert F Kennedy Invents a New Vaccine Conspiracy Theory, And It Could Kill Someone’, Science Daily, 27 March, online: https://www.sciencealert.com/robert-f-kennedy-tweets-a-ridiculous-conspiracy-theory-about-vaccinations

CDC (2013) ‘Understanding Thimerosal, Mercury, and Vaccine Safety’, February, online: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/patient-ed/conversations/downloads/vacsafe-thimerosal-color-office.pdf

CDC (2020a) ‘COVID-19 Pandemic Planning Scenarios’, US Centre for Disease Control and Prevention, 20 May, online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/planning-scenarios.html

CDC (2020b) ‘There is no link between vaccines and autism & Vaccine ingredients do not cause autism’, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, online: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/concerns/autism.html

Chalmers, Vanessa (2020) ‘150,000 Brits will die an ‘avoidable death’ during coronavirus pandemic through depression, domestic violence and suicides’, Daily Mail, 10 April, online https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-8207783/150-000-Brits-die-coronavirus-pandemic-domestic-violence-suicides.html

Chappell, Bill (2020) ‘Trump Says Funding Cuts Will Be Permanent If WHO Doesn’t Commit To ‘Major’ Changes’, NPR, 19 May, online: https://www.npr.org/sections/coronavirus-live-updates/2020/05/19/858579903/trump-says-cuts-to-who-funding-will-be-final-if-it-doesnt-commit-to-major-change

Chen, Wei (2020) ‘A Phase III clinical trial for inactivated novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) vaccine (Vero cells)’, Wuhan Institute of Biological Products, Chinese Clinical Trials Registry, 19 July, online: http://www.chictr.org.cn/showprojen.aspx?proj=56651

Cheng, Kar Keung; Tai Hing Lam and Chi Chiu Leung (2020) ‘Wearing face masks in the community during the COVID-19 pandemic: altruism and solidarity’, The Lancet, 16 April, online: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)30918-1/fulltext

Cohen, Jon (2020) ‘Chinese researchers reveal draft genome of virus implicated in Wuhan pneumonia outbreak’, Science Mag, 11 January, online: https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/01/chinese-researchers-reveal-draft-genome-virus-implicated-wuhan-pneumonia-outbreak

Criado, Miguel Ángel (2020) ‘Over half of coronavirus patients in Spain have developed neurological problems, studies show, El Pais, 17 July, online: https://english.elpais.com/science_tech/2020-07-17/over-half-of-coronavirus-hospital-patients-in-spain-have-developed-neurological-problems-studies-show.html

Dabo Guan, Daoping Wang, Stephane Hallegatte, Steven J. Davis, Jingwen Huo, Shuping Li, Yangchun Bai, Tianyang Lei, Qianyu Xue, D’Maris Coffman, Danyang Cheng, Peipei Chen, Xi Liang, Bing Xu, Xiaosheng Lu, Shouyang Wang, Klaus Hubacek, Peng Gong (2020) ‘Global supply-chain effects of COVID-19 control measures’, Nature Human Behaviour, DOI: 10.1038/s41562-020-0896-8

Damania, Zubin (2020) ‘Why Don’t We Know Exactly How Fatal COVID Is? A Doctor Explains’, ZDoggMD, YouTube, 7 July, online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5QjDOeaAZyw

Davis, Iain (2020) ‘Face Masks Have Put Us In A State’, OffGuardian, 22 June, online: https://off-guardian.org/2020/06/22/face-masks-have-put-us-in-a-state/

Definitive Healthcare (2020) ‘Effects of Postponing Essential Care Due to COVID-19, 24 June, online: https://blog.definitivehc.com/effects-of-postponing-essential-care-due-to-covid-19

DeStefano, Frank; Cristofer S. Price and Eric S. Weintraub (2013) ‘Increasing Exposure to Antibody-Stimulating Proteins and Polysaccharides in Vaccines Is Not Associated with Risk of Autism’, Journal of Paediatrics, pp. 561-567, online: https://www.jpeds.com/article/S0022-3476(13)00144-3/pdf?ext=.pdf

Donaldson, Liam J; Paul D Rutter, Benjamin M Ellis, Felix E C Greaves, Oliver T Mytton, Richard G Pebody, Iain E Yardley (2009) ‘Mortality from pandemic A/H1N1 2009 influenza in England: public health surveillance study’, BMJ; 339, 10 December, online: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b5213

Elaheh, Abdollah; David Champredon, Joanne M. Langley, Alison P. Galvani and Seyed M. Moghadas (2020) ‘Temporal estimates of case-fatality rate for COVID-19 outbreaks in Canada and the United States’, CMAJ Canada, 22 June, online: https://www.cmaj.ca/content/192/25/E666

EvaluatePharma (2017) ‘World Preview 2017, Outlook to 2022’, 10th edition, online: https://info.evaluategroup.com/WP2017-ENDP-FT.html

Also available here: https://www.skepticalraptor.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/EvaluatePharma-Pharma-Preview-2017.pdf

Finnegan, Conor and Josh Margolin (2020) ‘Pompeo changes tune on Chinese lab’s role in virus outbreak, as intel officials cast doubt: After telling ABC News there was “enormous evidence,” he now says maybe not’, ABC News, 8 May, online: https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/pompeo-tune-chinese-labs-role-virus-outbreak-intel/story?id=70559769

Fore, Henrietta H; Qu Dongyu; David M Beasley and Tedros A Ghebreyesus (2020) ‘Child malnutrition and COVID-19: the time to act is now’, The Lancet, 27 July, online: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)31648-2/fulltext

Foster, Gigi (2020) ‘Correctly counting the cost shows Australia’s lockdown was a mistake’, Financial Review, 25 May, online: https://www.afr.com/policy/economy/correctly-counting-the-cost-shows-australia-s-lockdown-was-a-mistake-20200525-p54w1o

Frost, W. H. (2020) ‘Statistics of Influenza Morbidity: With Special Reference to Certain Factors in Case Incidence and Case Fatality’, Public Health Reports (1896-1970), Vol. 35, No. 11 (Mar. 12, 1920), pp. 584-597, online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4575511

Gerber, Jeffrey S. and Paul A. Offit (2009) ‘Vaccines and Autism: A Tale of Shifting Hypotheses’, online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2908388/

Gibney, Katherine (2019) ‘Measles in Samoa: how a small island nation found itself in the grips of an outbreak disaster’, The Conversation, 12 December, online: https://theconversation.com/measles-in-samoa-how-a-small-island-nation-found-itself-in-the-grips-of-an-outbreak-disaster-128467

Glanz, James and Campbell Robinson (2020) ‘Lockdown delays cost at least 36,000 lives, data show’, New York Times, 22 May, online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/20/us/coronavirus-distancing-deaths.html

Gros, Daniel (2020) ‘The great lockdown: was it worth it?’, CEPS Policy Insights, May, online: https://www.ceps.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/PI2020-11_DG_The-great-lockdown.pdf

Hadler JL, Konty K, McVeigh KH, Fine A, Eisenhower D, Kerker B, et al. (2010) Case Fatality Rates Based on Population Estimates of Influenza-Like Illness Due to Novel H1N1 Influenza: New York City, May–June 2009. PLoS ONE 5(7), online: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0011677

Henderson, D.A. and Patra Klepac (2013) ‘Lessons from the eradication of smallpox: an interview with D. A. Henderson’, NCBI, Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci, Aug 5; 368(1623), online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3720050/

Hendrie, Doug (2020) ‘Why does the coronavirus fatality rate differ so much around the world?’, RACGP, 30 April, online: https://www1.racgp.org.au/newsgp/clinical/why-does-the-coronavirus-fatality-rate-differ-so-m

HHS (2020) ‘Vaccine Side Effects’, US Department of Health and Human Services, online: https://www.vaccines.gov/basics/safety/side_effects

Hitchens, Peter (2020) ‘Quite right @fraiseadam…’, Twitter, 23 June, online: https://twitter.com/ClarkeMicah/status/1275342496848121856

Holden, Emily (2020) ‘Climate science deniers at forefront of downplaying coronavirus pandemic’, The Guardian, 25 April, online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/25/climate-science-deniers-downplaying-coronavirus-pandemic

Holden, Richard and Bruce Preston (2020) ‘The costs of the shutdown are overestimated – they’re outweighed by its $1 trillion benefit’, The Conversation, 16 May, online: https://theconversation.com/the-costs-of-the-shutdown-are-overestimated-theyre-outweighed-by-its-1-trillion-benefit-138303

Howard, J.; Huang, A.; Li, Z.; Tufekci, Z.; Zdimal, V.; van der Westhuizen, H.; von Delft, A.; Price, A.; Fridman, L.; Tang, L.; Tang, V.; Watson, G.L.; Bax, C.E.; Shaikh, R.; Questier, F.; Hernandez, D.; Chu, L.F.; Ramirez, C.M.; Rimoin, A.W. (2020) ‘Face Masks Against COVID-19: An Evidence Review’, Preprints 2020, 2020040203 doi: 10.20944/preprints202004.0203.v1, online: https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202004.0203/v1

HRC (1999) ‘Human Rights Committee, General Comment 27, Freedom of Movement (Art.12), U.N. Doc CCPR/C/21/Rev.1/Add.9, online: http://hrlibrary.umn.edu/gencomm/hrcom27.htm

Hviid, Anders; Jørgen Vinsløv Hansen; Morten Frisch and Mads Melbye (2019) ‘Measles, Mumps, Rubella Vaccination and Autism: A Nationwide Cohort Study’, Ann Intern Med, Apr 16;170(8):513-520. doi: 10.7326/M18-2101, online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30831578/

IMF (2020) ‘The IMF’s Response to COVID-19’, 25 June, online: https://www.imf.org/en/About/FAQ/imf-response-to-covid-19#Q4

Isaacs, David (2020) ‘Lessons from the tragic measles outbreak in Samoa’, Journal of Paediatrics and Child health, Volume56, Issue1, January, pp. 175, online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/jpc.14752

John, Tara (2020) ‘Critics say lockdowns will be more damaging than the virus. Experts say it’s a false choice’, CNN, 29 May 29, online: https://edition.cnn.com/2020/05/29/europe/lockdown-skeptics-coronavirus-intl/index.html