Ethiopia’s Plan For Resolving The Amhara-Tigray Dispute Is Imperfect But Pragmatic

Ethiopia’s national interests are served by standardizing the resolution of interregional disputes through the means being employed in this case.

Ethiopia shared its plan for resolving the Amhara-Tigray dispute on the one-year anniversary of the Cessation Of Hostilities Agreement (COHA) with the TPLF. It envisages holding a referendum in the contested localities sometime after the return of all Internally Displaced People (IDP) and resumption of their farming activities, the establishment of local administrations selected from local residents, and the transfer of all security and law enforcement duties to federal forces.

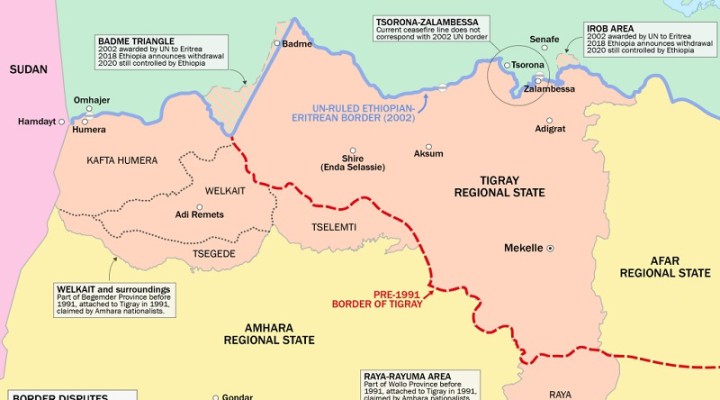

The disputed territory is considered by many Amhara to be part of their historical lands but to have been given by the TPLF to their Tigrayan co-ethnics as part of their divide-and-rule strategy after the civil war. That second-mentioned group, meanwhile, regards that part of the country as Western and Southern Tigray. The Northern Conflict that raged from 2020-2022 saw Amhara militias dislodge the TPLF from those areas as part of the federal government’s offensive, which inadvertently resulted in plenty of IDPs.

Over the past year since the COHA, Addis sought to reorganize regional special forces with a view to consolidating the federal government’s authority and thus preventing the outbreak of similar conflicts as the one that just ended. This was met with fierce resistance from many of these same Amhara with whom they’d earlier allied because some of them feared that the federal government would unilaterally resolve their territorial dispute with Tigray in the latter’s favor. Here are some background briefings:

* 9 April: “Ethiopia’s Military Reorganization Is Aimed At Preemptively Averting Another Tragedy”

* 11 April: “Extremely Sensitive Differences Of Perception Are Responsible For Ethiopia’s Amhara Protests”

* 24 April: “Ethiopia’s Negotiations With The OLA Align With PM Abiy’s Vision For His Country”

The last of these three pieces foresaw that Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed would eventually try resolve Ethiopia’s myriad interregional disputes such as the Amhara-Tigray one. It was predicted that “There’s no telling at this point whether that would involve unilateral actions at the federal level, grassroots democratically driven ones in each relevant area, or a combination thereof, but it’ll inevitably have to be done.” As it turns out, a combination of both unilateral and democratic approaches will be employed.

The first is evidenced through the planned return of all IDPs to the contested region, which aligns with the COHA’s clause stipulating that “Students must go to school, farmers, and pastoralists to their fields, and public servants to their offices” and conforms with international standards of conflict resolution. It’ll be unpopular with many Amhara militias and their local supporters, but therein lies one of the reasons why those groups were reorganized per this spring’s operation, namely to avert violence in this scenario.

This unilateral approach is required to facilitate the second democratic one wherein the pre-2020 population of this disputed region will then vote on whether to remain part of Tigray or join Amhara. Seeing as how the overwhelming majority are Tigrayans, the outcome is likely predetermined, thus suggesting that this dimension of the TPLF’s post-Civil War regional reorganization will remain in place. The standard being set for resolving this dispute through these means might then be applied to others.

This is an imperfect but pragmatic plan. It’s impossible to please all stakeholders in every interregional dispute, but these disputes have to be resolved one way or another for the greater good of the national interest as it objectively exists. The federal government is signaling that the pre-conflict demographic status quo in any given TPLF-inherited dispute will form the basis upon which they’ll be democratically resolved after all IDPs are returned to these areas and federal forces assume control of their security.

Ethiopia’s national interests are served by standardizing the resolution of such disputes through these means. Approving referendums in those areas according to their post-conflict demographic realities could encourage and even “reward” what can be described as the ethnic cleansing of some of their residents. Not only is that unacceptable for reasons of morality, but it could also lead to the country losing control of its many centrifugal processes, thus culminating in its full-fledged “Balkanization”.

The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia’s collapse into a collection of statelets formed around its dozens of ethno-linguistic groups would be to everyone’s detriment due to the inevitability of this scenario being driven by conflict, ethnic cleansing, and even genocide. The humanitarian consequences of such a development are unimaginable and that’s why no responsible policymaker would dare to risk this catastrophe, ergo the imperfect but pragmatic means employed by the government to avert it.

There’s no denying that the TPLF divided-and-ruled Ethiopia for self-interested political reasons during the over two decades that it controlled the country, but the case can be made that some aspects of this legacy will nevertheless remain no matter how unfair they are since it’s too dangerous to fix them. Those ethno-linguistic groups that were incentivized to move to contested territories and the ones that were forcibly removed from there can’t respectively be removed and returned without destabilizing the state.

This would require an unprecedented level of demographic (re-)engineering not seen since World War II and its immediate aftermath, which could stretch the military to the breaking point and prompt strong condemnation from the international community due to its innately anti-democratic methods. There’s no realistic way that this could be attempted without provoking another Civil War that would risk the earlier warned full-fledged “Balkanization” scenario and its catastrophic humanitarian consequences.

The national interests are objectively served in this case by sincerely trying to ensure the greatest amount of justice for the greatest amount of people while tacitly acknowledging that there’s no perfect solution and that some level of injustice (whether perceived or actual) will occur as a result. Considering this, for as unjust as some Amhara might regard the federal government’s plan for resolving their region’s dispute with Tigray, it’s arguably the so-called “lesser evil” considering the alternative.

All stakeholders have the right to express their opinion on this issue, though so long as they do so peacefully and in accordance with relevant laws prohibiting hate speech, disinformation, incitement to violence, etc. It’s understandable that the federal government’s imperfect but pragmatic approach will upset some folks, but everyone should keep objectively existing national interests in mind before publicly reacting to it in order to not unwittingly endanger their shared Ethiopian homeland with all that entails.

https://korybko.substack.com/p/ethiopias-plan-for-resolving-the

TheAltWorld

TheAltWorld

0 thoughts on “Ethiopia’s Plan For Resolving The Amhara-Tigray Dispute Is Imperfect But Pragmatic”