The Iran-Azerbaijan standoff is a contest for the region’s transportation corridors

Sides are forming around the Iran vs Azerbaijan squabble. But this fight is not about ethnicity, religion or tribe – it is mainly about who gets to forge the region’s new transportation routes.

The last thing the complex, work-in-progress drive towards Eurasian integration needs at this stage is this messy affair between Iran and Azerbaijan in the South Caucasus.

Let’s start with the Conquerors of Khaybar – the largest Iranian military exercise in two decades held on its northwestern border with Azerbaijan.

Among the deployed Iranian military and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) units there are some serious players, such as the 21st Tabriz Infantry Division, the IRGC Ashura 31 battalion, the 65th Airborne Special Forces Brigade and an array of missile systems, including the Fateh-313 and Zulfiqar ballistic missiles with ranges of up to 700 kilometers.

The official explanation is that the drills are a warning to enemies plotting anything against the Islamic Republic.

Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei pointedly tweeted that “those who are under the illusion of relying on others, think that they can provide their own security, should know that they will soon take a slap, they will regret this.”

The message was unmistakable: this was about Azerbaijan relying on Turkey and especially Israel for its security, and about Tel Aviv instrumentalizing Baku for an intel drive leading to interference in northern Iran.

Further elaboration by Iranian experts went as far as Israel eventually using military bases in Azerbaijan to strike at Iranian nuclear installations.

The reaction to the Iranian military exercise so far is a predictable Turkey–Azerbaijani response: they are conducting a joint drill in Nakhchivan throughout this week.

But were Iran’s concerns off the mark? A close security collaboration between Baku and Tel Aviv has been developing for years now. Azerbaijan today possesses Israeli drones and is cozy with both the CIA and the Turkish military. Throw in the recent trilateral military drills involving Azerbaijan, Turkey and Pakistan – these are developments bound to raise alarm bells in Tehran.

Baku, of course, spins it in a different manner: Our partnerships are not aimed at third countries.

So, essentially, while Tehran accuses Azerbaijan’s President Ilham Aliyev of making life easy for Takfiri terrorists and Zionists, Baku accuses Tehran of blindly supporting Armenia. Yes, the ghosts of the recent Karabakh war are all over the place.

As a matter of national security, Tehran simply cannot tolerate Israeli companies involved in the reconstruction of regions won in the war near the Iranian border: Fuzuli, Jabrayil, and Zangilan.

Iranian Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdullahian has tried to play it diplomatically: “Geopolitical issues around our borders are important for us. Azerbaijan is a dear neighbor to Iran and that’s why we don’t want it to be trapped between foreign terrorists who are turning their soil into a hotbed.”

As if this was not complicated enough, the heart of the matter – as with all things in Eurasia – actually revolves around economic connectivity.

An interconnected mess

Baku’s geoeconomic dreams are hefty: the capital city aims to position itself at the key crossroads of two of the most important Eurasian corridors: North-South and East-West.

And that’s where the Zangezur Corridor comes in – arguably essential for Baku to predominate over Iran’s East-West connectivity routes.

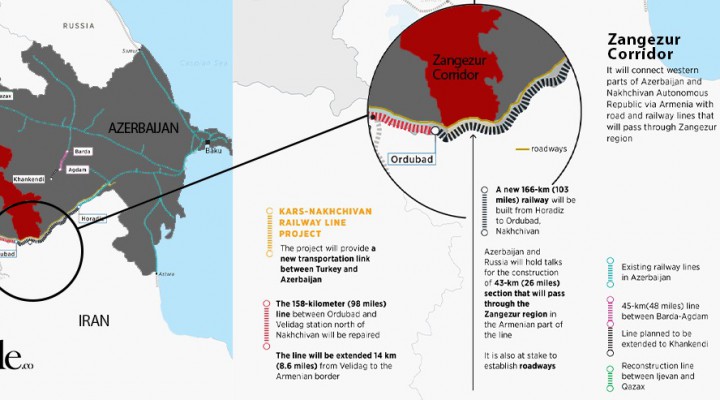

The corridor is intended to connect western Azerbaijan to the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic via Armenia, with roads and railways passing though the Zangezur region.

Zangezur is also essential for Iran to connect itself with Armenia, Russia, and further on down the road, to Europe.

China and India will also rely on Zangezur for trade, as the corridor provides a significant shortcut in distance. Considering large Asian cargo ships cannot sail the Caspian Sea, they usually waste precious weeks just to reach Russia.

An extra problem is that Baku has recently started harassing Iranian truckers in transit through these new annexed regions on their way to Armenia.

It didn’t have to be this way. This detailed essay shows how Azerbaijan and Iran are linked by “deep historical, cultural, religious, and ethno-linguistic ties,” and how the four northwestern Iranian provinces – Gilan, Ardabil, East Azerbaijan and West Azerbaijan – have “common geographical borders with both the main part of Azerbaijan and its exclave, the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic; they also have deep and close commonalities based on Islam and Shiism, as well as sharing the Azerbaijani culture and language. All this has provided the ground for closeness between the citizens of the regions on both sides of the border.”

During the Rouhani years, relations with Aliyev were actually quite good, including the Iran‑Azerbaijan‑Russia and Iran‑Azerbaijan‑Turkey trilateral cooperation.

A key connectivity at play ahead is the project of linking the Qazvin‑Rasht‑Astara railway in Iran to Azerbaijan: that’s part of the all-important International North‑South Transport Corridor (INSTC).

Geoeconomically, Azerbaijan is essential for the main railway that will eventually run from India to Russia. No only that; the Iran‑Azerbaijan‑Russia trilateral cooperation opens a direct road for Iran to fully connect with the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU).

In an optimal scenario, Baku can even help Iranian ports in the Persian Gulf and the Sea of Oman to connect to Georgian ports in the Black Sea.

The West is oblivious to the fact that virtually all sections of the INSTC are already working. Take, for instance, the exquisitely named Astara‑Astara railway connecting Iranian and Azerbaijani cities that share the same name. Or the Rasht‑Qazvin railway.

But then one important 130km stretch from Astara to Rasht, which is on the southern shore of the Caspian and is close to the Iranian–Azeri border, has not been built. The reason? Trump-era sanctions. That’s a graphic example of how much, in real-life practical terms, rides on a successful conclusion of the JCPOA talks in Vienna.

Who owns Zangezur?

Iran is positioned in a somewhat tricky patch along the southern periphery of the South Caucasus. The three major players in that hood are of course Iran, Russia, and Turkey. Iran borders the former Armenian – now Azeri – regions adjacent to Karabakh, including Zangilan, Jabrayil and Fuzuli.

It was clear that Iran’s flexibility on its northern border would be tied to the outcome of the Second Karabakh War. The northwestern border was a source of major concern, affecting the provinces of Ardabil and eastern Azerbaijan – which makes Tehran’s official position of supporting Azerbaijani over Armenian claims all the more confusing.

It is essential to remember that even in the Karabakh crisis in the early 1990s, Tehran recognized Nagorno‑Karabakh and the regions surrounding it as integral parts of Azerbaijan.

While both the CIA and Mossad appear oblivious to this recent regional history, it will never deter them from jumping into the fray to play Baku and Tehran against each other.

An extra complicating factor is that Zangezur is also mouth-watering from Ankara’s vantage point.

Arguably, Turkey’s neo-Ottoman President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who never shies away from an opportunity to expands his Turkic-Muslim strategic depth, is looking to use the Azeri connection in Zangezur to reach the Caspian, then Turkmenistan, all the way to Xinjiang, the Uyghur Muslim populated western territory of China. This, in theory, could become a sort of Turkish Silk Road bypassing Iran – with the ominous possibility of also being used as a rat line to export Takfiris from Idlib all the way to Afghanistan.

Tehran, meanwhile, is totally INSTC-driven, focusing on two railway lines to be rehabilitated and upgraded from the Soviet era. One is South-North, from Jolfa connecting to Nakhchivan and then onwards to Yerevan and Tblisi. The other is West-East, again from Jolfa to Nakhchivan, crossing southern Armenia, mainland Azerbaijan, all the way to Baku and then onward to Russia.

And there’s the rub. The Azeris interpret the tripartite document resolving the Karabakh war as giving them the right to establish the Zangezur corridor. The Armenians for their part dispute exactly which ‘corridor’ applies to each particular region. Before they clear up these ambiguities, all those elaborate Iranian and Tukish connectivity plans are effectively suspended.

The fact, though, remains that Azerbaijan is geoeconomically bound to become a key crossroads of trans-regional connectivity as soon as Armenia unblocks the construction of these transport corridors.

So which ‘win-win’ is it?

Will diplomacy win in the South Caucasus? It must. The problem is both Baku and Tehran frame it in terms of exercising their sovereignty – and don’t seem particularly predisposed to offer concessions.

Meanwhile, the usual suspects are having a ball exploiting those differences. War, though, is out of the question, either between Azerbaijan and Armenia or between Azerbaijan and Iran. Tehran is more than aware that in this case both Ankara and Tel Aviv would support Baku. It is easy to see who would profit from it.

As recently as April, in a conference in Baku, Aliyev stressed that “Azerbaijan, Turkey, Russia and Iran share the same approach to regional cooperation. The main area of concentration now is transportation, because it’s a situation which is called ‘win‑win.’ Everybody wins from that.”

And that brings us to the fact that if the current stalemate persists, the top victim will be the INSTC. In fact, everyone loses in terms of Eurasian integration, including India and Russia.

The Pakistan angle, floated by a few in hush-hush mode, is completely far-fetched. There’s no evidence Tehran would be supporting an anti-Taliban drive in Afghanistan just to undermine Pakistan’s ties with Azerbaijan and Turkey.

The Russia–China strategic partnership looks at the current South Caucasus juncture as unnecessary trouble, especially after the recent Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) summit. This badly hurts their complementary Eurasian integration strategies – the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the Greater Eurasian Partnership.

INSTC could, of course, go the trans-Caspian way and cut off Azerbaijan altogether. This is not likely though. China’s reaction, once again, will be the deciding factor. There could be more emphasis on the Persian corridor – from Xinjiang, via Pakistan and Afghanistan, to Iran. Or Beijing could equally bet on both East-West corridors, that is, bet on both Azerbaijan and Iran.

The bottom line is that neither Moscow nor Beijing wants this to fester. There will be serious diplomatic moves ahead, as they both know the only ones to profit will be the usual NATO-centric suspects, and the losers will be all the players who are seriously invested in Eurasian integration.

TheAltWorld

TheAltWorld

0 thoughts on “The Iran-Azerbaijan standoff is a contest for the region’s transportation corridors”