Saudi-Iran pact: China’s diplomatic coup puts US on notice in Middle East

One year ago, I wondered whether the war in Ukraine would accelerate the US withdrawal from the Middle East. While there is not yet a clear answer, I correctly assessed that some regional actors, “anticipating an American disengagement”, would act accordingly.

China has acted quickly to fill the perceived political void. President Xi Jinping visited Saudi Arabia last December and met all Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) members. In February, Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi visited Beijing.

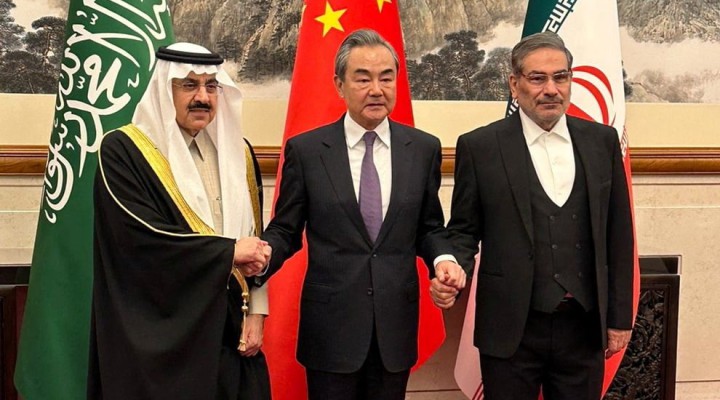

Then, on 10 March, a trilateral statement from Saudi Arabia, Iran and China announced an agreement between Riyadh and Tehran to resume diplomatic relations. Both countries reaffirmed their respect for state sovereignty and non-interference in other countries’ internal affairs.

While the Ukraine war continues to monopolise the primary attention of Washington and its allies, dynamics in the Middle East are once again accelerating. As the old motto goes, you can ignore the Middle East – but rest assured the Middle East will not ignore you.

The China-brokered agreement restores a minimum of normality after seven years of severed ties between Riyadh and Tehran. Ideally, it should mark a “turning point in a tumultuous relationship” dating back to Iran’s 1979 Islamic revolution.

Facilitated by Iraq and Oman, Saudi Arabia and Iran had been engaging in bilateral talks since early 2021. Large parts of their deal were already agreed upon, but China cleverly jumped at the opportunity to finalise it.

This is a clear success for Beijing – its first in the troubled Middle East region – and it could be followed by others. China is even planning an unprecedented high-level meeting between Arab monarchs and Iranian officials in Beijing later this year. It would be difficult to imagine a bigger slap in the face to US Middle Eastern diplomacy.

‘Unipolarity no longer exists’

The Chinese Communist Party’s unofficial English-language mouthpiece, the Global Times, hyped the agreement as “another proof that unipolarity no longer exists and that we are already in a de facto multipolar world order”, adding: “The Middle East and the world are not only in a post-America order, but also in a post-West order.”

The 1980 Carter Doctrine, which considered the Gulf to be exclusively a US sphere of influence, is over.

The deal increases China’s global standing, but it is also important to its energy security. The Gulf is a key supplier of oil to China, so its leadership has an understandable vested interest in stabilising the area. Essentially, China has replaced the soft power that the EU – to no avail – attempted to display in the area for decades, further confirming Europe’s ongoing global marginalisation.

The US official reaction made the best of a bad situation, with National Security Council spokesman John Kirby welcoming China’s efforts to de-escalate regional tensions. To a certain extent, such de-escalation coincides with US interests. In principle, the last thing Washington should want now is further trouble in the Middle East, while it is mobilising against Russia in Ukraine and escalating tensions with China over Taiwan.

The Iran-Saudi agreement shows to the GCC states, and by extension the “Global Rest”, that there is another world out there with different options. China has shown itself to be a great power that behaves differently from the US and offers alternatives in geopolitics. This is not a trivial issue in a world that is supposed to be managed according to rules conceived and enforced by the US.

The Global Rest would do well to take note of China’s new model of diplomacy: no ideological blinders, no Manichean characterisation of the “Other”, no economic sanctions, no currency weaponisation, no military threats – just patient, fairly brokered dialogue built upon realities on the ground and cognitive empathy.

Beijing has also cleverly exploited Washington’s missteps. US passivity after the strike on Saudi oil facilities in 2019, and tensions about oil output levels last autumn, provided an interesting signal on Saudi Arabia’s shifting priorities – an opportunity that China leveraged immediately by offering the Shangai Petroleum and Natural Gas Exchange as a platform for yuan settlement of oil and gas trade.

If reports that Saudi Arabia will cut production and stop selling oil to any country that imposes a price cap on its supplies are confirmed, this could have significant political implications on its relations with the US and on energy markets.

Not only could Pax Sinica replace Pax Americana in the region, but the petroyuan may replace the petrodollar.

Abraham Accords

Inevitably, the China-brokered Saudi-Iran deal also triggers a comparison with the 2020 US-brokered Abraham Accords. Here, again, the two great powers’ different modi operandi should not go unnoticed by the Global Rest.

Contrary to usual US diplomacy in the region, with Saudi Arabia and Iran, China was an honest broker. Too often, instead, Washington acts as Israel’s lawyer. The Trump administration paved the way for the normalisation of relations between Israel on one side and Bahrain, Morocco, the UAE and Sudan on the other – but it accomplished this by throwing Palestinians under the bus.

The Biden administration has had opportunities to adjust its policies, but it has refrained from doing so. It acted illogically on its commitment to restore the nuclear deal with Iran, and it maintained Trump’s provocative position on Jerusalem, as well as a deafening silence amid relentless Israeli settlement activity.

Only when the latest far-right Israeli government began to tolerate pogroms and hinted at ethnic cleansing, did the current US administration feel compelled to convey its uneasiness. Too little, too late, probably; after all, when you have been outsourcing the intellectual crafting of a large part of your Middle Eastern policy to Israel for decades, sooner or later, blowback should be expected.

An important test of the Saudi-Iran deal will be whether, and how, it affects the tense relationship between the US and Israel on one side, and Iran on the other, due to the nuclear file. In recent weeks, Iran has appeared closer to weapons-grade nuclear enrichment.

While Israel is increasingly nervous about this prospect, Washington and Tel Aviv are not always on the same page on this topic. Still, in light of the deal, is it realistic to expect Saudi Arabia to facilitate an Israeli strike on Iran’s nuclear facilities?

The real cherry atop the Abraham Accords would be Saudi Arabia joining, but it is unlikely to do so while Israel’s extremist government is deliberately killing the two-state solution and engaging in a creeping annexation of the West Bank. Even the UAE is having second thoughts on the accords, while it is also embroiled in tensions with the US over Russia sanctions.

The Saudi-Iran rapprochement could bolster expectations for a wider regional de-escalation, including an end to the Yemen war, a proxy conflict that has caused one of the biggest – and least mainstream-media-covered – humanitarian catastrophes of the 21stcentury. It could also hopefully have a positive impact on the Syrian war and Lebanon’s political deadlock and economic collapse.

The shifting world order is symbolised by the fact that the Middle East is becoming another litmus test of the respective foreign policies and political narratives of the US and China. Meanwhile, Xi is expected in Moscow next week. Is another Chinese diplomatic surprise in the making?

https://www.middleeasteye.net/opinion/china-saudi-iran-reconciliation-middle-east-diplomatic-coup

TheAltWorld

TheAltWorld

0 thoughts on “Saudi-Iran pact: China’s diplomatic coup puts US on notice in Middle East”