The Rise of Jamie Dimon

As JPMorgan’s ties to Jeffrey Epstein are being scrutinized in court, Whitney Webb reveals how the same powerful players who brought Epstein to prominence were largely responsible for the rise of JPMorgan CEO, Jamie Dimon.

Earlier this month, a judge ruled that two different lawsuits against JPMorgan Chase over the bank’s ties to deceased “financier” and pedophile, Jeffrey Epstein, would be allowed to advance in U.S. Courts. One of these cases, brought against the bank by the U.S. Virgin Islands (USVI), has been a particular focus of independent media since the new year began, in part because the Attorney General of the USVI, Denise George, was fired from her post just days after she filed that case.

In a hearing in the USVI case against JPMorgan earlier this month, a USVI lawyer argued that the CEO of JPMorgan – Jamie Dimon – “knew in 2008 that his billionaire client [Jeffrey Epstein] was a sex trafficker.” The lawyer, Mimi Liu, also stated that former JPMorgan Jes Staley also knew this about Epstein at the time, but noted: “This case was not just Jes Staley … there will be numerous documents that go far beyond his office to the executive suite.” Liu also asserted that “Staley knew, Dimon knew, JPMorgan Chase knew” about Epstein’s criminal activities against minors.

While the bank has disputed that Dimon knew anything about Epstein’s accounts at the bank or what he was really up to at the time, this Unlimited Hangout investigation – a multi-part series – will reveal that Dimon’s rise to the top post at JPMorgan was intimately linked to the very same group of people who enabled Jeffrey Epstein’s sex trafficking activities as well as his extensive financial crimes.

In this article, we will examine how Dimon’s rise to become one of the most powerful men on Wall Street was largely reliant on top executives and directors of Bank One, which boasts incredibly close ties to The Limited’s Leslie Wexner and his right-hand man for many decades, Columbus-area real estate developer John W. Kessler. Kessler and other individuals tied to Wexner were the dominant forces that saw Dimon installed as Bank One’s CEO in 2000. Bank One was acquired by JPMorgan in 2003 and, shortly thereafter, Dimon became CEO of the combined entity. That acquisition, as well as the role of the Crown family in Chicago in Dimon’s selection as Bank One’s CEO, will be discussed in the second part of this series.

Yet, Dimon’s ties to the same networks as Wexner, particularly those characterized by their connections to organized crime and intelligence, preceded his time as Bank One’s CEO by many years. As this article will show, Dimon’s construction of what is now Citigroup, alongside his mentor Sandy Weill, began with their takeover of a company called Commercial Credit Corporation. That company, as well as its parent company, Control Data Corporation, had a troubling history of ties to intelligence networks that were extensively involved in criminal activity – including the so-called “private CIA” formed by CIA veteran Ted Shackley in the 1970s as well as individuals crucial to the Epstein story like Robert Maxwell.

Given these connections, JPMorgan’s claims that Dimon never knew what Jeffrey Epstein was up to during his time with the bank becomes much harder to believe. Furthermore, as future installments of this series will show, the players discussed here – Dimon and Epstein among them – were instrumental in the creation of what would manifest as the 2008 economic crisis. Not unlike some of the events that sparked today’s banking crisis, figures like Jeffrey Epstein, Dimon’s mentor Sandy Weill and the former Treasury Secretaries with close associations with both men, Robert Rubin and Larry Summers, appeared to have engaged in actions that would intentionally provoke the collapse of certain banks to further consolidate the banking sector for their benefit. The goal, both then and now, seems to have been a move towards the logical conclusion of the “too big to fail” banking model — the eventual creation of a centralized cartel of mega-banks that dominate, not only commercial banking, but also central banking.

A Brief History of Control Data Corporation

Created by a group of Naval engineers in 1956, at the dawn of the American military-industrial complex, Engineering Research Associates (ERA) was a military contractor with a focus on cryptography and code-breaking. Shortly after its creation, part of the core ERA team split off and formed Control Data Corporation (CDC) a year later in 1957.

CDC quickly became a defense contractor in its own right and became a major purveyor of super-computers to sensitive U.S. research facilities. These included Sandia National Laboratories and Oak Ridge Laboratories, both of which worked on the U.S. nuclear program. At the same time, CDC also had an odd relationship with the Soviet Union’s own sensitive nuclear facilities, which eventually led to congressional scrutiny. Congressional hearings from the mid-1970s revealed that:

In 1968, a second-generation Control Data Corporation 1604 system was installed at the Dubna Soviet Nuclear Facility near Moscow. In 1972 [CDC] sold the Soviet Union a third-generation CDC 6200 system computer. For these systems, [CDC’s] operating statement had improved by about $3 million dollars in the past three years. And the Soviet Union has gained 15 years in computer technology

The hearings also noted that CDC planned to sell Soviet-controlled Poland computer systems so sensitive that they were only used domestically at the National Security Agency (NSA) and the Atomic Energy Commission. CDC claimed that Poland planned to use the equipment at a Polish “high school.” At the time, no American high school or educational institution of any type possessed this particular system, and there were only 10 in the entire country. As reflected by these and other examples in the hearings’ transcripts, Congress’ concerns were based around the perception that CDC’s business in the USSR involved technology transfers that undermined U.S. national security during the height of the Cold War. Those concerns would only grow with time.

After these hearings in 1974, CDC made an apparent move at increasing its role in technology transfers, despite political concerns. By the late 1970s, they had established a new subsidiary called Worldtech, described in the press as “a division of Control Data Corp that does research and consulting on, and brokering of, technology transfers.”

Once Worldtech was established by CDC, it entered into a joint venture in 1979 with Greek publisher George Bobolas that was called Worldtech Hellas Ltd. 70% was owned by Bobolas and 20% was owned by CDC. The owner of the remaining 10% was not disclosed in reports at the time.

A 1979 letter from one of Bobolas’ companies to A. Afonin, identified as a “representative of the State Committee for Foreign Economic Relations of the USSR Council of Ministers,” proposed the creation of a “joint development company using Worldtech for ‘world-wide technology transfer’” and stressed that “Worldtech Hellas Ltd. will give a lot of help’ to ‘technology transfer on an international base.’” After journalist Paul Anastasi published information about Bobolas and called him a “KGB agent of influence,” one of his companies, Bobtrade, asserted that “no improper transfer of high technology was involved.” CDC moved to dissolve their partnership, likely due to bad publicity.

Around the time that Worldtech was created, CDC’s then-executive vice president, Robert D. Schmidt, was part of the American Committee on U.S.-Soviet Relations (ACUSR, previously the American Committee on East-West Accord). Other members at the time, specifically in 1977, included Robert Maxwell’s lawyer and confidant, Samuel Pisar (stepfather to current U.S. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken), as well as Thomas Watson Jr. of IBM, who would become the U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union in 1979. Another member was Paul Ziffren, a major figure in the organized crime networks that ran through Chicago and Hollywood described in Gus Russo’s acclaimed work Supermob. Another key figure in the “Supermob” network was Henry Crown. Crown, along with his son and grandson – Lester and James, will be discussed in greater detail later in this series due to their pivotal role in the rise of Jamie Dimon.

Notably, in the early 1970s, Samuel Pisar told Congress that the world was moving “toward a single, unified world economy, in disregard of national frontiers, and even ideological boundaries.” He stated that “all conventional tools of national policy, it seems to me, are rapidly becoming anachronistic [as] the State itself, even a strong one, [..] is no longer a defendable economic entity.” Pisar also claimed that the main drivers of this shift included “the multinational corporation” and “the dissemination of technology.” He later frames technology transfers by major multinational corporations as giving rise to the “trans-ideological corporation” where “capital private enterprises” and “Communist state enterprises” freely intermingled and formed joint ventures. When asked if these “trans-ideological corporations” were forces for good or for evil, Pisar responded that “I believe that on balance, they are a force for good,” but qualified that as depending on how governments and corporate management act “to make certain that they become forces for good.”

By the mid-1980s, Occidental Petroleum executives Armand Hammer and William McSweeney had also joined the ACUSR. Samuel Pisar also represented Hammer’s business interests. Hammer notably served as a back channel between the Americans and the Soviets and had once sought to acquire the American bank First General Bancshares (FGB) for the purpose of “financially blackmailing” US politicians, specifically members of Congress who had open accounts at the bank. It is also worth mentioning that Hammer’s father, Julius Hammer, had once served as a Soviet spy.

Another member of the ACUSR was Joseph Filner, president of Noblemet International (later renamed the Newmet Corporation). Filner was extensively involved in USSR-U.S. tech transfers. Filner’s Noblemet created a joint venture for the purpose of tech transfers, which was called Multi-Arc. By 1984, CDC’s Worldtech had become “a worldwide marketing representative for Multi-Arc.”

CDC would later recruit Minnesota governor Rudy Perpich after Perpich lost his re-election campaign in 1979. Perpich, a dentist by training, would specifically work for CDC overseas as “vice president and executive consultant to Control Data Worldtech Inc.”The New York Times, reporting on his hire by CDC in January 1979, stated that Perpich was expected to be based in Yugoslavia, but he said he could find himself in Hungary, Bulgaria or Rumania [sic].” Robert Maxwell was also intimately involved with tech transfers in Eastern Europe, specifically in Bulgaria, through the Bulgarian intelligence-linked Neva program that specifically targeted and pirated Western-developed technologies. Perpich, after working for Worldtech, went on to win another term as Minnesota’s governor in 1983.

CDC, by that time, had also recruited another influential politician, Walter Mondale. Mondale was hired by CDC right after he left office as Jimmy Carter’s vice president. CDC hired Mondale as a legal consultant and retained his services for $2,000 per month (about $6,537 in 2023 dollars).

Simultaneously, Mondale was also a consultant to Allen & Co, the company of the organized crime-linked brothers Charles and Herbert Allen. Mondale was not only a consultant to, but also a close friend of the Allen brothers. The Allen brothers also worked closely with organized crime interests as well as Leslie Wexner’s “mentors” Max Fisher and Alfred Taubman and he also had “a close business association with Earl Brian and had financed one of his attempts to buy out Bill Hamilton’s Inslaw.” Brian, along with Israeli spymaster Rafi Eitan, was the architect of the theft of the PROMIS software originally created by Hamilton’s company, Inslaw Inc. Brian’s lawyer, Allan Tessler, also served on the board of Les Wexner’s company The Limited and had a close business relationship with another organized crime-linked family, the Gouletas. The Gouletas family notably shared office space with Jeffrey Epstein while Epstein was working as Wexner’s financial advisor in the late 1980s.

CDC was itself tied up with the PROMIS theft and the resulting scandal. The PROMIS software, after its theft, was bugged by both Israel intelligence and a separate group that involved the CIA, the “Supermob”-linked company MCA, and Latin American drug cartels. This latter group’s version was used to spy mostly on financial institutions. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, investigative journalist Danny Casolaro was writing a book that covered, among other things, this group’s repurposing of PROMIS for financial espionage and money laundering. Shortly before his untimely death in 1991, those close to the journalist had seen documents obtained by Casolaro that detailed money transfers from the World Bank to Earl Brian as well as Saudi arms dealer and Iran-Contra figure Adnan Khashoggi. Notably, throughout the 1980s, Khashoggi had retained the financial services of Jeffrey Epstein.

It appears that this version of PROMIS and its use at the World Bank involved CDC in some capacity. By 1983, CDC was providing its services to the World Bank’s computer center and, that same year, the PROMIS software was found to be in use at that specific facility to keep track of wire transfers of money. This comes from a sworn statement that Inslaw Inc. obtained from David McCallum in 1995. In 1983, McCallum was working for CDC at the World Bank.

In my correspondence with Inslaw’s Bill Hamilton, he stated the following:

According to an article in the International Banking Regulator dated January 17, 1994, U.S. Justice Department officials delivered the VAX version of PROMIS to the World Bank in 1983. The World Bank, as an international institution, is outside the reach of discovery of the U.S. courts. For its part, the World Bank declares that it has been unable to find any evidence that it ever possessed the VAX version of PROMIS.

Hamilton also relayed that he had once been informed of a connection between CDC and PROMIS that involved the Deputy Attorney General under Ed Meese, D. Lowell Jensen. However, he could no longer remember the specifics of that connection.

Also significant is the role CDC played during the 1990 visit of Mikhail Gorbachev, the then-leader of the Soviet Union, to the United States. During that trip, Gorbachev visited CDC headquarters alongside Rudy Perpich, as well as Robert Maxwell. The Gorbachevs arrived in Minnesota immediately after a summit meeting in Washington with then-President George H.W. Bush.

According to a report from the Minnesota Historical Society:

Gorbachev most likely agreed to the visit [Minnesota] because several Minnesota-based corporations – especially the computer firm, Control Data Corporation – had long done business in the Soviet Union. When the corporation’s officials learned that Gorbachev was interested in a post-summit tour, they passed the word to Perpich, who had worked for Control Data between his two terms as governor. Albert Eisele, who had been a consultant for Control Data and, earlier, was Vice President Walter Mondale’s press secretary, drafted the governor’s letter inviting the Gorbachevs. Former Control Data CEO Robert Price personally delivered the letter to the Soviet embassy on February 26, 1990.

During the visit, Gorbachev attended a lunch at the governor’s mansion, where Robert Maxwell and Rudy Perpich joined groups of Soviet and American officials. One of the American officials present was Condoleezza Rice, the future Secretary of State who was then a National Security Council staff member. Afterwards, there was a press conference where Robert Maxwell, in characteristic bombastic fashion, “announced that he would donate $50 million to help create a private research institution to be called the Gorbachev-Maxwell Institute of Technology.” Maxwell said that the donation was “contingent on Perpich raising matching funds.” However, the institute was never launched.

After visiting Minnesota, Gorbachev next visited Silicon Valley, where he spent the week “trying to perfect the art of winning acceptance and investment from the captains of capitalism.” A Washington Post article on his visit quoted John Sculley, then-head of Apple Computers as saying, “I think Gorbachev got to us… We’ll all be thinking about business with the Soviet Union in a way we wouldn’t have if he hadn’t come.”

Notably, Apple’s Steve Jobs was advised by Samuel Pisar. Jobs later stated that his 1985 trip the USSR has been “facilitated by an international lawyer based in Paris” and that Jobs had a “feeling” that this attorney “worked for the CIA or the KGB.” That lawyer was almost certainly Pisar.

Commercial Credit Corporation and the “private CIA”

In 1968, CDC acquired the Commercial Credit Corporation (CCC) to “help its computer customers finance leases of company hardware and stabilize erratic earnings” that then characterized much of the early computer industry. A few years after the acquisition, both CDC and CCC would find themselves intertwined with the “private CIA” network developed mainly by Ted Shackley, the Agency’s infamous “Blond Ghost,” in the late 1970s and which later allied itself with George H.W. Bush. This is highly significant as this particular network was intimately involved with the illicit transfers of both weapons and technology, including during the Iran-Contra scandal, the related PROMIS scandal, and the subsequent “Chinagate” scandal of the mid-1990s.

For example, around 1976, CDC hired the “rogue” CIA agent Edwin Wilson as a consultant. Wilson, who later was sent to prison when he was caught illegally selling weapons to Libya, has been described as “part spy, part tycoon” and used a web of corporations he controlled to benefit his benefactors in the CIA and the Office of Naval Intelligence. Wilson had long worked closely with Ted Shackley. He was also allegedly involved in sexual blackmail operations involving both the American CIA and the South Korean CIA at Washington DC’s Georgetown Club. CDC purportedly hired Wilson so he could help the company “unload some outdated computers on Third World countries.”

Yet, CDC leveraged Wilson’s extensive contacts and abilities for much more, going so far as to have Wilson bug the U.S. Army’s Materiel Command on behalf of the company. The company was apparently seeking “inside information … on bidding and procurement plans” of the military. Given CDC’s role in illicit technology transfer, its ties to organized crime and intelligence-linked networks and its explicit espionage activity targeting the U.S. military, it seems fair to say that CDC was much more than just a technology company.

CCC, for its part, also had odd connections to the networks around Shackley. For instance, one of the key components of this “private CIA” was a company created by Shackley and another CIA operative and long-time associate of Shackley’s named Thomas Clines. That company was known as the Egyptian-American Air Transport and Services Corporation, or EATSCO. It seems that EATSCO functioned as a middleman in arms sales made by the Pentagon to Egypt and, later, other countries.

EATSCO’s primary support apparatus in this regard was an airline called Global International Airways, which was based in Kansas and founded in the late 1970s by Farhad Azima. Azima was reportedly tied to Iran’s pre-revolutionary intelligence apparatus, SAVAK, and – according to author Joseph Trento – was a frontman for the “private CIA.” Trento further alleges in his book Prelude to Terror that Global International had actually been designed by James Cunningham, who had previously worked under Shackley as the manager of the CIA’s Air America. Air America, later renamed Southern Air Transport, would relocate to Columbus, Ohio in the mid-1990s as part of a deal negotiated by Leslie Wexner’s The Limited and, according to local reporters in the Columbus area, his then-money manager, Jeffrey Epstein.

What is particularly notable for the purposes of this article is how Global International was initially financed. It turns out that Azima was only able to launch the airline after he was given, for reasons that remain unclear, a “multi-million dollar loan from the Commercial Credit Corporation.”

A few years after it was acquired CDC, both Commercial Credit Corporation and its parent company were floundering. In 1985, two men would arrive, take over CCC, and turn the troubled, intelligence-linked financial services company into what is now the massive megabank Citigroup. Those men were Sanford “Sandy” Weill and his young apprentice, Jamie Dimon.

The Beginning of “Too Big to Fail”

Sandy Weill began his Wall Street career at Bear Stearns in 1955. There, he was a colleague of Alan “Ace” Greenberg, who would later head Bear Stearns and hire controversial figures such as Jimmy Cayne and Jeffrey Epstein. Greenberg would later say of Weill that, during his brief time at Bear Stearns, “it was easy to see he was a winner.”

By 1960, Weill had left Bear Stearns and teamed up with four friends to create their own brokerage firm, which was first named Carter, Berlind, Potoma & Weill. After the departure of Arthur Carter and Peter Potoma, the firm later became known as CBWL when Marshall Cogan, who previously had worked at CBS and the investment firm Orvis & Co., and Arthur Levitt, the future chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) during the Clinton administration and later adviser to the intelligence-linked Carlyle Group, joined the firm.

A decade later, in 1970, Weill organized what would be the first of many takeovers. His target was Hayden Stone and his company then became CBWL-Hayden Stone. In 1974, Weill again went on the offensive and acquired Shearson Hammill, creating Shearson Hayden Stone. After several more acquisitions, Loeb, Rhoades was also acquired and the combined firm became Shearson Loeb Rhoades. It is during this period that Weill would first encounter a young Jamie Dimon.

Jamie Dimon’s father and grandfather had both been top stockbrokers at Shearson and a young Dimon briefly worked for the firm one summer while on break from Tufts University. Dimon’s parents had befriended Sandy Weill and, one day, gave Weill an economics term paper Jamie had written about CBWL-Hayden Stone’s acquisition of Shearson. Weill was impressed with the paper and Dimon asked Weill for a summer job.

Dimon, after graduating from Tufts, attended Harvard Business School and worked over the summer, not at Shearson but at Goldman Sachs. Around this time, Weill sold Shearson Loeb Rhoades to American Express in 1981 for $1 billion. As part of the deal, Weill became American Express’ president. In 1982, as Dimon was about to graduate, Weill approached Dimon and asked him to work for him at American Express as his executive assistant. For nearly two decades, Dimon would continue to serve as Weill’s apprentice.

About three years later, in 1985, Weill was forced out of American Express. Weill urged Dimon to stay at the company, but Dimon chose the somewhat riskier option of continuing to work for Weill despite the uncertainty of the path ahead. They went on the hunt for a financial services company in need of a drastic turnaround and eventually settled on Commercial Credit Corporation in 1986. According to an academic study of Dimon’s early career from Harvard Business School, it was Weill and Dimon who identified CCC and then convinced Control Data Corporation to spin off their troubled consumer-lending subsidiary. However, a different account in Fortune magazine claims that Weill were approached by two financial officers at CCC who, “without a breathing a word to their CEO,” came to Weill “to urge that he buy the company from its owner, Control Data.” Regardless of which account is more accurate, the company tied to illicit tech transfers to the USSR and the “private CIA” would, within a decade or so, grow into a Wall Street titan.

Weill took control of the company in September 1986, becoming its President and CEO and taking the company public. Dimon served as the company’s Chief Financial Officer and an Executive Vice President, later becoming its President. An old bio of Dimon’s describes him as “a key member of the team that launched and defined the strategy for Commercial Credit Company in October 1986.” About a year after the acquisition, Weill’s CCC bought back Control Data’s remaining stake in the company.

In August 1988, CCC acquired Primerica Corporation, the parent company of brokerage firm Smith Barney. Despite being the buying company, Weill and Dimon decided to shed the CCC name. A year later, the new Primerica acquired 16 Drexel, Burnham & Co. branches and also acquired the branch offices and loan portfolio of Barclays American Financial, an American subsidiary of Barclays Bank PLC. In 1992, Primerica bought a 27% stake in the insurance giant Travelers and went on to buy the remainder of Travelers later the following year. In this same period, Weill and Dimon purchased Shearson back from American Express, which – per Weill – “changed everything.” At the end of 1993, Weill was CEO of the new entity, Travelers Group, and Dimon was President and its Chief Operating Officer. A few years later, Travelers Group would acquire Salomon Brothers, merging it with Smith Barney. Dimon became the CEO and Chairman of the new Salomon Smith Barney.

1993 was also an important year for a friend of Weill’s, former Goldman Sach’s head Robert Rubin. Rubin had just become the director of President Clinton’s National Economic Council and was the person who signed off on Jeffrey Epstein’s first visit to the Clinton White House in February 1993. Epstein would make 17 visits to the White House in total between February 1993 and January 1995, many of them tied to Clinton-era fundraising scandals. During this time, Epstein’s name was mysteriously dropped from the case regarding the Towers Financial Ponzi Scheme, despite him being labeled the “mastermind” of the scheme in grand jury testimony. Shortly after Clinton left office, Epstein would play a pivotal role in creating the Clinton Foundation, which critics have derided as a Clinton family “slush fund.”

Robert Rubin became Treasury Secretary in 1995 and, in that capacity, would later work with Weill to consecrate the marriage between Weill’s Travelers Group and Citicorp in the late 1990s, creating Citigroup and one of the biggest “too big to fail” banks of today. This merger necessitated, among other things, the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act. Rubin would later be rewarded by Weill with a lucrative position at Citigroup. The role of Weill, Rubin and Rubin’s deputy, Larry Summers, in the repeal of Glass-Steagall and the 2008 economic crisis will be discussed in another installment of this series. Notably, Larry Summers, whose close relationship with Epstein is a matter of record, began his friendship with the deceased pedophile while he was Rubin’s deputy (if not earlier).

The partnership between Weill and Dimon would fall apart shortly after the creation of Citigroup. According to some who were close to Weill and Dimon around this time, the tensions between the two were palpable in 1998. At the time, a Citigroup spokesperson told the New York Times that a restructuring of the bank’s leadership hierarchy, which “would have offered Mr. Dimon less authority at Citigroup than he wanted and that ultimately led to his departure.” Several years later, in 2010, Weill told the New York Times that Dimon had pushed to be Citi’s CEO at a time when Weill wasn’t ready to retire. In the years that followed, Weill softened his account of their parting even more, lamenting in 2014 that the two hadn’t “been able to work out [their] issues” and continue their partnership.

Like Weill had been after his ouster from American Express in 1985, Dimon’s future after Citigroup was uncertain. He was offered jobs from a variety of companies, including Amazon, but turned them all down as he waited for the right “financial services” opportunity to come along. That opportunity would come in the year 2000, as Bank One hunted for a new CEO.

Bank One – The bank behind Leslie Wexner and The Limited]

Bank One was founded in Columbus, Ohio in 1870 as City National Bank (CNB) and – for much of the 20th century – was run by the McCoy family. John G. McCoy took over the firm from his father, John H. McCoy, in 1958 and, very early on, sought to identify ways that technology could improve convenience for customers. As a result, CNB was an early adopter of the credit card and the forerunner of the automated teller machine (ATM) in the late 1960s. Over the next several decades, CNB ballooned in size, acquiring 22 small Ohio banks within a holding company that would later become Banc One. Banc One (perhaps confusingly) later became Bank One after a merger in the mid-90s and up until its acquisition by JPMorgan. To avoid confusion, the remainder of this article will refer to the bank as Bank One.

Sometime before his retirement in 1984, John G. McCoy was a banker for many Columbus area businesses, including Leslie Wexner’s The Limited. Little information is available regarding the specifics of the relationship between Wexner’s business interests and Bank One prior to the mid-1980s.

However, Wexner’s right hand man throughout the 1980s, 1990s and beyond – John “Jack” Kessler – was very close to John G. McCoy. Kessler, who became friends with Wexner when they both attended Ohio State University, later claimed that John G. McCoy had been his “biggest mentor” and “like a second father.” He also went on to note that he had been put on Bank One’s board by John G. McCoy when Kessler “was a very young man.” When Kessler was asked about what “lasting lessons” he learned from John G. McCoy, he responded:

How you conduct yourself in business. Ethics and your reputation. He always gave us talks – he did the same with Les [Wexner], who was also very close to him – making sure you give back to your community.

Records of Bank One reported on by Harvard Business School faculty list Kessler’s Date of Hire (DOH) to the bank’s board as 1986, when Kessler was 50 years old and when John G. McCoy’s son – John B. McCoy – had already taken the reigns at the bank. Regardless of whether Kessler’s connection to the bank preceded 1986 or not, both Kessler and Wexner were close to John G. McCoy and Kessler would continue to have a very close connection with the bank well after it was acquired by JPMorgan in the early 2000s.

Wexner for his part, was also on Bank One’s board of directors during the 1990s (and potentially earlier) and, as will be noted again later, Wexner’s The Limited even held “unclaimed funds” belonging to the bank, suggesting very close ties between Wexner’s businesses and the bank. In 1996, Wexner stated of McCoy that “John has been a mentor, both to me and The Limited, for many years.” As we will see, it is very possible that Wexner’s less than legal financial activities, which would later include his patronage of and association with Jeffrey Epstein, may have been learnt from John G. McCoy, as Bank One under his tenure reportedly became involved in – among other things – money laundering on behalf of Israel intelligence.

John G. McCoy retired as the head of the bank in 1984, with his son – John B. McCoy – taking over. Around this same time, state banking laws were altered to allow bank holding companies to acquire banks in different states. This led Bank One to begin rapidly acquiring banks throughout the country, including in Indiana, Kentucky, Texas, Arizona, Wisconsin and Louisiana. The dramatic growth of Bank One via numerous acquisitions eventually earned John B. McCoy a spot on Forbes’ list of the six bankers who built up the main “too big to fail banks” of today. One of the other six, unsurprisingly, is Sandy Weill.

The mid-1980s were a time of great change for Bank One and it was also a time of great change for Leslie Wexner, his businesses and his business associates. Some of the changes for Wexner during this period, which would see Jeffrey Epstein enter his inner circle, were spurred by a grisly murder. In 1985, the tax attorney for The Limited, Arthur Shapiro, was shot in the face in a murder that, still today, remains unsolved. Shapiro was murdered just a day before he was due to testify to the IRS in a case related to his filing of fraudulent tax returns.

As Unlimited Hangout previously reported on the case:

As an unindicted co-conspirator, Shapiro would not have been indicted himself, but he could have provided damaging information regarding those who had been indicted, giving considerable motive to [Berry] Kessler and the other co-conspirators—unnamed in the [Columbus] Dispatch or other media reports at the time—to see that Shapiro did not testify. What is odd about this court case, beyond the significant fact that a key witness had been shot in what police referred to as a “mob style murder” or “mafia hit,” is that Kessler and his co-conspirators were only sentenced to probation and did not serve prison time for the crime of helping Shapiro file false tax returns in 1971 and 1976.

This raises several questions: Why was Shapiro an unindicted co-conspirator if he was the one who filed the fraudulent tax returns, while those charged were convicted of aiding Shapiro file the false returns? Does that mean Shapiro had planned to testify about other individuals involved in a bigger scheme, who were not part of this particular case, in exchange for avoiding tax-fraud charges against himself? Also, why were those convicted given such lenient sentences despite Shapiro’s planned testimony being the most likely motive for his high-profile murder?

It is fair to say that none of these questions have ever been answered properly by Ohio authorities. However, a few years after Shapiro was killed, Elizabeth Leupp – an analyst with Columbus Police’s Organized Crime Bureau, sent a report to her superior Curtis Marcum. It soon made its way to the then-Columbus Police Chief James Jackson, who quickly suppressed the document and ordered it destroyed. It was accidentally released to local Ohio journalist Bob Fitrakis in response to a Freedom of Information Act request he had filed about a different matter. The censored document discusses in detail how Shapiro’s murder was seen by police as a mob-style murder and it extensively detailed the organized crime connections of two of Ohio’s wealthiest men – Leslie Wexner and a business partner of Wexner’s, Edward DeBartolo Sr.

The document also extensively mentioned John Kessler. It states that the investigation into Shapiro’s death became “more complex” after “unusual interactive relationship between the following business organizations” were revealed. These organizations are listed in order as: The Major Chord Jazz Club, tied to former Columbus City Council President Jeremy Hammond; Wexner’s The Limited and its investment interests; Walsh Trucking Company, operated by Frank Walsh who had known connections to the Genovese crime family; Arthur Shapiro’s law firm, which dropped Shapiro’s name from the firm hours after his death; The Edward DeBartolo Corporation, which also had documented organized crime connections detailed in the report; and John W. Kessler, who is referred to in the report as a “local developer.”

Regarding Walsh Trucking, it is worth noting that – when New York law enforcement attempted to subpoena Walsh’s bank records in investigating his organized crime ties, his address was listed as The Limited’s corporate headquarters. In addition, the DeBartolo family’s ties to organized crime are actually much more extensive than Leupp noted in her report and those details can be found in a previous Unlimited Hangout investigation on the topic as well as the book One Nation Under Blackmail, Vol. 2.

Regarding Kessler, one of the suspect businesses detailed in the report is referred to as the W & K Partnership, which Leupp believed to be the Wexner & Kessler partnership and a forerunner to the New Albany project that the two men eventually co-founded. The partnership, Leupp notes, had invested a significant amount of money in Hammond’s Jazz Club. As the report later states, the financial tie of this partnership to Hammond was apparently used to essentially bribe Hammond so he would support controversial legal changes in Franklin County to benefit the Wexner-Kessler New Albany project, which had lobbied extensively for those changes despite public opposition.

Notably, Kessler, as well as Hammond, were later investigated by Columbus police in connection with some of the activity detailed in Leupp’s report as well as corruption involving public contracts. Yet, by the time of the grand jury in 1995, Leupp’s report had already been taken out of circulation by the Columbus Police Chief. Kessler and Hammond were ultimately not charged due to “insufficient evidence.” Oddly, the prosecutors involved in the case declined to call either Kessler or Hammond to testify when both had agreed to do so, suggesting that the prosecutors pursued the claims against both men half-heartedly.

In Leupp’s report, Kessler’s firm – the John W. Kessler company – is also listed as sharing office space with the New Albany Company and firm called PFI Leasing, where Wexner’s money manager before Jeffrey Epstein, Harold Levin, was listed as Vice President. Epstein, after he rose to the top of Wexner’s inner circle, had taken over that position at PFI Leasing from Levin by 1990. It is noted in the report that a lawyer from Arthur Shapiro’s firm had been caught speeding in a vehicle registered to PFI Leasing, suggesting that this company was used to offer “perks”, such as lent vehicles, to people operating within Wexner’s network.

Another company in this same location was originally named Lewex, but was later renamed Parkview Financial. Levin was listed as Vice President of Parkview until 1990, when that position also became Epstein’s. Parkview Financial then became a major vehicle for both Wexner’s and Epstein’s activities in the New York City real estate market, several of which tie into properties linked to his sex trafficking activities and Ossa Properties, the real estate company run by Epstein’s brother – Mark Epstein – and former employees of Epstein’s J. Epstein & Co.

In the report – and elsewhere – Kessler is portrayed as one of Wexner’s closest associates and, as previously mentioned, co-founded the New Albany project with Wexner. An article in the Cleveland Plain Dealer, cited by Fitrakis, said the following of the genesis of the project: “Wexner and Kessler formed the New Albany Co. and spun off a bunch of paper corporations to cover their footprints. Then their minions knocked on doors and made the proverbial offers you couldn’t refuse.”

Jeffrey Epstein got involved in the New Albany project around 1988, shortly after becoming a financial advisor to Wexner. He was eventually a general partner in the real-estate holding company, New Albany Property. This, of course, means that Epstein would have known Kessler quite well. Bob Fitrakis, quoted in Vicky Ward’s 2003 piece on Epstein in Vanity Fair, stated of the relationship that “Before Epstein came along in 1988, the financial preparations and groundwork for the New Albany development were a total mess […] Epstein cleaned everything up.” Ward notes the oddity of Epstein having a general partnership in New Albany Property “despite putting only a few million dollars of capital into the project.” Epstein was also given a luxury home in the development by Wexner, which he later sold.

At the same time Epstein was advising Wexner and becoming a partner in New Albany alongside Kessler, he was also helping to orchestrate one of the largest Ponzi schemes in U.S. history with Steven Hoffenberg via Hoffenberg’s company Towers Financial. Epstein had previously described his work after he left Bear Stearns in 1981 as that of a “financial bounty hunter” and that he had helped “hide and find looted money” for powerful people, including Iran-Contra figures like Adnan Khashoggi. Given that New Albany and its apparent predecessor, the W & K partnership, were intimately involved in the web of companies tied to Arthur Shapiro’s murder and considering Epstein’s prior work history, it seems possible that what Epstein helped to “clean up” at New Albany may have involved activities that were less than legal.

Wexner, Kessler and Epstein were not the only noteworthy residents of New Albany as far as this article is concerned. One of the first wealthy elites of Columbus that bought property in the luxury development was none other than John G. McCoy, Bank One’s head from 1958 to 1984 and “mentor” to both Kessler and Wexner. Today, the New Albany Community Foundation has an award named in honor John G. McCoy and both Kessler and Wexner are past recipients.

The Bank One Laundromat

Bank One, in the early 1990s, had an apparent relationship with a controversial data processing and bank software firm tied to the aforementioned PROMIS scandal and financial espionage. That company, Systematics, was controlled by the intelligence-linked Arkansas businessman and political kingmaker Jackson Stephens. Stephens, who played a major role in the rise of the Clinton family, tapped Little Rock’s Rose law firm, where Hillary Clinton worked, to represent Systematics. Systematics has long been of interest to researchers of the PROMIS scandal, with the late journalist Michael Ruppert referring to the company as “a primary developer of PROMIS for financial intelligence use.”

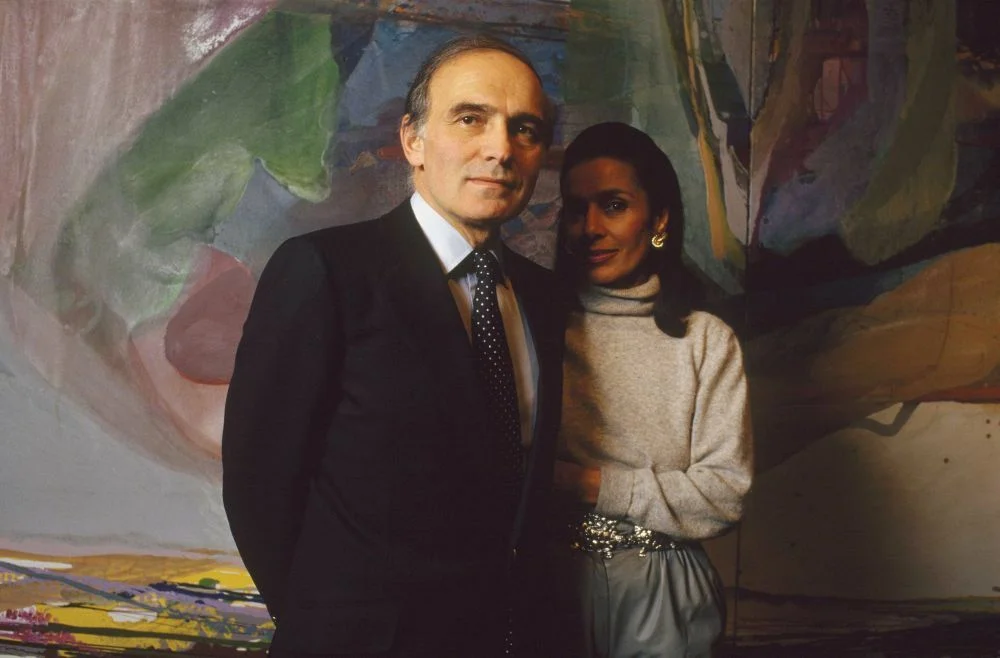

Arkansas businessman Jackson Stephens; Source

Systematics had very close ties to American intelligence, including the NSA and CIA, and was alleged to be a “money-shuffler for covert operations.” Systematics also had a relationship with the Bank of Credit and Commerce International (BCCI) and was a contractor to BCCI’s American subsidiary First American. BCCI, as noted in One Nation Under Blackmail, was essentially a private intelligence apparatus masquerading as a bank and – in addition to money laundering for intelligence agencies and organized crimes – was directly involved in the sex trafficking of minors in order to curry favor with bank “VIPs” and the ruling elite of countries like the United Arab Emirates.

Systematics also had connections to Israeli intelligence. It had a subsidiary in Boston as well as Israel that employed undercover Mossad agents and focused on the sale of software to banks. Systematics also entered into a joint venture with Israel intelligence operative and media mogul Robert Maxwell. Maxwell, who was also Israel’s most successful salesman of the bugged PROMIS software, teamed up with Systematics to sell PROMIS to five banks, most of which were Swiss.

Bank One’s ties to Systematics came through its acquisition of Team Bancshares Inc., which had already entered into a multi-year data processing contract with Systematics at the time of the merger. Bank One eventually cancelled that contract in favor of a competitor. At the time of these events, Systematics had recently become a subsidiary of Alltel, where Jackson Stephens also had a major stake. In fact, Jackson Stephens, after the merger, became Alltel’s single largest shareholder and Stephens’ son Warren Stephens was placed on the Alltel board.

An unspecified “major” stake in Alltel was notably held by Lester Crown, the son of “Supermob” associate Henry Crown. Lester Crown was a founding member of the Leslie Wexner-created “Mega Group” and his son, James S. Crown, would play a major role in the activities of Bank One after 1995, including the hire of Jamie Dimon to lead the bank. The Crowns are discussed in-depth in the next installment of this series.

Per reports, the time that Bank One had a contract with Systematics after it merged with Team Bancshares was relatively brief. However, Bank One – for many years prior – had also been involved with much of the covert activity that Systematics had helped enable, particularly money laundering for intelligence agencies.

Former Israeli spy Ari Ben Menashe mentions Bank One’s role in laundering funds for Israeli intelligence-brokered arms deals, deals in which Ben Menashe had been personally involved. In his book, Profits of War, he states the following about how Israeli intelligence received money from its arms sales to Iran with the involvement of banks like Bank One as well as U.S. intelligence:

A letter of credit from the Iranian government would be issued to an Israeli “front” company by a European-based Iranian company through the London or Paris branch of Iran’s Bank Melli. It would be endorsed by the National Westminster Bank in England, and we would then ask for it to be transferred to an American Bank. Favorites were the Chicago-Tokyo Bank in Chicago, the Chemical Bank in New York, Bank One in Ohio, and the Valley National Bank of Arizona. Then the banks would have to explain these letters of credit, in U.S. dollars, to the U.S. Treasury if they were to accept them. According to U.S. Treasury regulations, letters of credit for sums in excess of $10,000 had to be approved by the Treasury.

Since the sales were a U.S.-sanctioned operation, the CIA would have to ensure that Treasury issued an acceptance. Once the letter of credit was approved, it was moved back again to Europe. Except for the John Street operations in 1981-1982, this was to be the way almost all American-supplied arms sales to Iran were handled from late 1981 until late 1987.

In other words, from 1981-1987, Bank One was a “favorite” bank of Israel intelligence for the laundering of arms dealing profits. Notably, all but the first of these four “favorite” banks are now part of JPMorgan.

What’s particularly interesting about this passage from Profits of War is that one of the other banks mentioned, Valley National Bank, was later acquired by Bank One in 1992, shortly after Bank One acquired Team Bancshares. This is notable for a few reasons as Valley National Bank appears in a separate part of Ben Menashe’s book, where Ben Menashe states that he deposited $4 million on behalf of Israeli intelligence into a Valley National Bank account owned by PROMIS scandal architect Earl Brian. That money, per Menashe, was likely to have originated from Latin American drug sales. Valley National Bank was also known to provide multi-million dollar loans to Charles Keating’s American Continental Corporation (ACC). In addition, Cindy McCain, wife of late Senator John McCain, wrote checks to Keating’s ACC from her personal Valley National account. John McCain was one of the “Keating Five” and was accused of corrupt dealings involving Keating, a white collar criminal who played a major role in the S & L crisis of the 1980s and who was also a figure in the banking circles surrounding BCCI.

It’s also worth mentioning that the head of Valley National, Richard Lehmann, remained in charge of the bank after its acquisition by Bank One, at which point it became Bank One Arizona. Just three years after the acquisition, in 1995, Lehmann became president and chief operating officer of the entire Bank One Corporation, where he worked directly with John B. McCoy.

In addition, another of Bank One’s acquisitions, which took place a few years before it acquired Valley National, saw them absorb another bank with unsettling connections. In 1989, 20 banks owned by Mcorp failed and were taken over by the FDIC in what was, at the time, the second most expensive bank rescue in U.S. history. The FDIC awarded all those banks to Bank One. Mcorp had been the result of a merger between the Mercantile Texas Corporation and Bank of the Southwest, which took place in 1984. The latter bank had a close relationship with a Houston-based foundation that moved CIA money called the San Jacinto fund. The person who ran that fund, Ernest Cockrell Jr., was also a board member of Bank of the Southwest. In addition, the Bank of the Southwest had a close relationship with the M.D. Foundation, which had funnelled CIA money to an international lawyer group at the Agency’s request.

Bank One’s connections to these networks brings up an obvious question: Did such networks also intersect with Leslie Wexner and his businesses? As I noted in One Nation Under Blackmail, former investment banker and government official Catherine Austin Fitts, who has extensively investigated the intersection of organized crime, Wall Street and the government in the U.S. economy, was told by an ex-CIA official that Wexner was one of five key managers of organized crime cash flows in the U.S. As previously mentioned, Wexner had organized crime connections, including through his business partner, Edward DeBartolo Sr., and the man who was managed much of The Limited’s logistical business domestically, Frank Walsh.

In addition, from 1992 to 1995, Wexner’s The Limited played a major role in courting two different CIA-connected airlines to relocate to Rickenbacker airfield in Columbus, Ohio to ostensibly run “cargo” for The Limited. They ultimately settled on Southern Air Transport, formerly the CIA’s Air America and one of the main airlines implicated in illicit activities in the Iran-Contra scandal. The relocation of Southern Air to Ohio was also notably secured with the help of Alan Fiers Jr., the former chief of the CIA Central American Task Force, and Richard Secord, the former head of Air America’s covert action in Laos in the late 1960s. Secord was also the air logistics coordinator for Oliver North during Iran-Contra, while Fiers had also been intimately involved in the scandal.

Bob Fitrakis has claimed that Epstein, who was involved in logistics planning for The Limited at the time, was also part of this deal. Epstein had his own connections to Iran-Contra era arms deals through his former client Adnan Khashoggi and one of his mentors, British arms dealer Douglas Leese. The relocation of Southern Air Transport to Ohio and the beginning of the airline’s partnership with The Limited notably occurred in 1995, when Wexner was also on the board of Bank One.

If Bank One’s leadership, during the 1980s, participated in money laundering for Iran-Contra era arms deals and the bank’s leadership – John G. McCoy and his son – were so close to Wexner, the possibility of such a connection is high. There is also the following to consider – The Limited was apparently holding onto “unclaimed funds” belonging to Bank One in the 1990s, when Wexner and Kessler were both on the bank’s board. Yet, reports quizzically claimed that neither state officials nor The Limited could “find” the bank to return the money.

As the Columbus Dispatch reported in 1995:

Banc One has branch offices all over Ohio and its headquarters are across the street from the Statehouse, but apparently state officials can’t find the multibillion-dollar banking operation. The name of the nation’s eighth-largest bank holding company shows up on the state’s list of owners of unclaimed funds.

But Ohio is not alone. The Limited, which is holding the funds, couldn’t find the banking company either, even though Leslie H. Wexner, the specialty retailer’s chairman, sits on Banc One’s board of directors.

The claim that state officials and the business of a bank’s board member “couldn’t find” Bank One to return their “unclaimed funds” to them is odd on its own. Even crazier is the idea that Bank One’s “unclaimed funds” would be held by The Limited, nominally a retail business, and not another bank or a state institution.

Dimon Rising

Though Wexner was no longer on Bank One’s board at the time Jamie Dimon was hired, John Kessler was. Kessler, who has acknowledged his role in selecting Dimon as the bank’s CEO, has sung Dimon’s praises for many years. Yet, also crucial to Dimon’s hire as well as John B. McCoy’s abrupt departure from the bank was James S. Crown and a top executive at the Sara Lee Corporation, a Crown-controlled company. Both men were directors of the First Chicago NBD bank, which merged with Bank One in 1995.

James Crown’s father, Lester Crown, was close to Wexner, having been a member of the “Mega Group”, which Wexner co-founded with Charles Bronfman in 1991. His grandfather, Henry Crown, was a major figure in the aforementioned “Supermob” network as well as a major figure in the American defense industry through his control of defense contractor General Dynamics. The next installment of this series will examine the Crown family in detail as well as their dominant role at First Chicago NBD and how they spurred McCoy’s ouster from Bank One and the hunt for a new CEO. Dimon’s arrival to Bank One and his time there up until he became CEO of JPMorgan will also be discussed.

https://unlimitedhangout.com/2023/03/investigative-series/the-rise-of-jamie-dimon/

Acknowledgements: Ed Berger contributed research to this report.

This investigative series is sponsored by the Solari Report.

TheAltWorld

TheAltWorld

Guy

Stay safe Whitney .You are the best .

fc koln specialudgave trøje

Denne her kategori finder du et bredt udvalg af FC Köln fodboldtrøjer på tværs af forskellige sæsoner, inklusive hjemmebanetrøjer, bortetrøjer, alternative trøjer og specielle specialudgaver for 2024-2025 og 2025-2026.[web:8] Køberen kan filtrere og sortere trøjerne efter popularitet, nyeste modeller eller beløb og derefter bestemme størrelsesvariant, spillers navn, nummer og patches for at gøre trøjen skræddersyet.[web:8] Butikken tilbyder gratis fragt over et givent beløb, hurtig kundeservice og sikker betaling med almindelige kreditkort, hvilket gør det problemfrit for FC Köln-fans at købe deres næste Bundesliga-trøje via nettet.[web:8]