Tanzania’s Late President Magufuli: ‘Science Denier’ or Threat to Empire?

While his COVID-19 policies have dominated media coverage regarding his disappearance and suspicious death, Tanzania’s John Magufuli was hated by the Western elites for much more than his rebuke of lockdowns and mask mandates. In particular, his efforts towards nationalizing the country’s mineral wealth threatened to deprive the West of control over resources deemed essential to the new green economy.

Jeremy Loffredo & Whitney Webb– Less than 2 weeks ago, Tanzanian Vice President Samia Suluhu Hassan delivered the news that her country’s president, John Pombe Magufuli, had died of heart failure. President Magufuli had been described as missing since the end of February, with several anti-government parties circulating stories that he had fallen ill with COVID-19. During his presidency, Magufuli had consistently challenged neocolonialism in Tanzania, whether it manifested through the exploitation of his country’s natural resources by predatory multinationals or the West’s influence over his country’s food supply.

In the months leading up to his death, Magufuli had become better known and particularly demonized in the West for opposing the authority of international organizations like the World Health Organization (WHO) in determining his government’s response to the COVID-19 crisis. However, Magufuli had spurned many of the same interests and organizations angered by his response to COVID for years, having kicked out Bill Gates-funded trials of genetically-modified crops and more recently angering some of the most powerful mining companies in the West, companies with ties to the World Economic Forum and the Forum’s efforts to guide the course of the 4th industrial revolution.

Indeed, more threatening than his recent COVID controversies was the threat Magufuli posed to foreign control over the world’s largest, ready-to-develop nickel deposit, a metal essential to electric car batteries and thus the current effort to usher in an electric, autonomous vehicle revolution. For instance, just a month before he disappeared, Magufuli had signed an agreement to begin developing that nickel deposit, a deposit that had been previously co-owned by Barrick Gold and Glencore, the commodity giant deeply tied to Israel’s Mossad, until Magufuli revoked their licenses for the project in 2018.

Running afoul of the most powerful corporate and banking cartels followed then by the mysterious onset of sudden regime change would normally garner considerable coverage from anti-imperialist independent media outlets, which recently covered similar events in Bolivia that led to the removal of Evo Morales from power. However, the very outlets that have extensively covered Western-backed regime change efforts for years have been entirely silent on the very convenient death of Magufuli. Presumably, their silence is related to Magufuli’s flouting of COVID-19 narrative orthodoxy, as these same outlets have largely promoted the official narrative of the pandemic.

Yet, regardless of whether one agrees with Magufuli’s response to COVID, his sudden departure and Tanzania’s new leadership is a defeat for a widely popular domestic movement that sought to mitigate and reverse the centuries-long exploitation of Tanzania by the West. Now, with Magufuli’s lengthy disappearance followed by his apparent sudden death from heart failure, the country’s future is now set to be determined by Tanzanian politicians with deep ties to the oligarch-beholden United Nations and the World Economic Forum.

In contrast to Magufuli, who routinely stood up to predatory corporations and imperialist designs on his country, Samia Suhulhu and Tanzanian opposition politician Tundu Lissu are poised to offer up their country’s resources, and their population, on the altar of the Western elite-driven 4th industrial revolution.

Magufuli’s celebrated rise and his clashes with the West

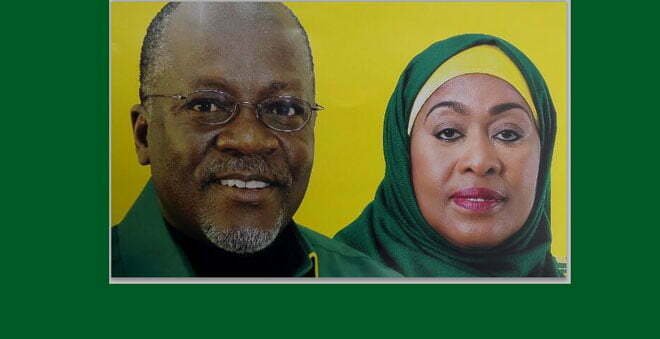

Magufuli was first elected with his running mate and now president of Tanzania, Samia Suhulu, back in 2015 with 58% of the vote. At first, the president was met with lavish praise from the same Western media outlets that would later seek to demonize him. For instance, a BBC report from 2016 reflected on Magufuli’s first year in office and noted his 96% approval rating. The report also quoted political analyst Kitila Mumbo, who remarked, “there is no doubt that President Magufuli is very popular among many ordinary Tanzanians” and added that “the president’s main promise of extending free education to secondary school, which came into effect in January, has been well received.”

Also in 2016, CNN had reported that “the Tanzanian public has gone wild for its new President John Magufuli” and that “after sweeping to victory in October 2015, Magufuli has embarked on a remorseless purge of corruption.” The article reported that Magufuli had inspired a new term, as seen in Tanzanians’ social media posts:

“ … ‘Magufulify’ – defined as: ‘To render or declare an action faster or cheaper; 2. to deprive [public officials] of their capacity to enjoy life at taxpayers’ expense; 3. to terrorize lazy and corrupt individuals in society.’”

Indeed, Magufuli’s term was characterized by making decisions that benefited the majority of Tanzanians, largely at the expense of foreign corporations but also by overhauling a government known for its entrenched corruption and absenteeism prior to Magufuli’s rise. His administration cut the salaries of the executives at state-owned companies, as well as his own salary, from $15,000 to $4,000 USD. Some State parades and celebrations were reduced or cancelled to cover the expenses of public hospitals.

Healthcare had long been one of Magufuli’s priorities, and the life expectancy of the country significantly increased every year he was in office. In addition, in the previous 50 years of Tanzanian independence, only 77 district hospitals were constructed, whereas during the past 4 years alone, 101 such hospitals were constructed and equipped with local funds. By July 2020, the country had grown from a so-called lower income country to a middle income country, per the World Bank.

A recent report by the hawkish, US establishment think tank, the Center for Strategic International Studies (CSIS), was highly critical of Magufuli, but noted the following about his political philosophy:

“Magufuli, who subscribes to his own homegrown “Tanzania first” philosophy, believes that Tanzania has been cheated out of profit and wealth by exploitative mabeberu (“imperialists”) since independence. To secure populist support, Magufuli has fashioned his agenda as a continuation of the socialist vision of Tanzania’s first president, Mwalimu Julius Nyerere, who advocated self-reliance, an intolerance to corruption, and a strong nationalist character.”

Magufuli’s various conflicts with the mabeberu transpired throughout his presidency, targeting various projects and business ventures of corporations and oligarchs that have worked to exploit much of the Global South for decades. For example, in late 2018, Tanzania’s government ordered a stop to all ongoing field trials on genetically modified (GM) crops and the destruction of all plants grown as part of those trials. Those trials were being conducted by a partnership called the Water Efficient Maize for Africa (WEMA) project, which was a collaboration between Monsanto and the African Agricultural Technology Foundation, a non-profit funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the Rockefeller Foundation, GM seed/agrochemical giant Syngenta, PepsiCo and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), long known to be a cut-out for the CIA. Then, in January of 2021, a month before Magufuli’s disappearance, Tanzania’s agriculture ministry not only announced a cancellation of all “research trials involving genetically modified organisms (GMOs) in the country” for the second time, it also announced plans to institute new biosafety regulations aimed at protecting Tanzania’s food sovereignty by scrutinizing western GM seed imports.

Historically, the US has been particularly harsh to countries that resist the integration of GM biotech into their food systems. According to a State Department cable from 2007 published by Wikileaks, Craig Stapleton, then-US Ambassador to France, advised the US to prepare for economic war with countries unwilling to introduce Monsanto’s GM corn seeds into their agricultural sectors. He recommended the US “calibrate a target retaliation list that causes some pain across the E.U.” for the bloc’s resistance to approving some GM products. In another cable from 2009, a US diplomat stationed in Germany relayed intelligence on Bavarian political parties to several US federal agencies and the US Secretary of Defense, telling them which parties opposed Monsanto’s M810 corn seed and spoke of “tactics that the US could impose to resolve the opposition.”

The US government’s use of food as a weapon for imperialist agendas became de facto policy when Henry Kissinger was Secretary of State during the Nixon administration. During that period, a classified report was produced by the State Department that argued that the population of the developing world threatened US national security and posited that food aid be used as an “instrument of national power” to advance US empire.

A roadblock for the Ruling Class’ “green” future

Magufuli’s role in robbing Big Ag of a foothold in Tanzania a month before his disappearance and death certainly casts suspicion on the circumstances surrounding his demise. Yet, if that weren’t enough, Magufuli, during the exact same time frame, greatly angered the most powerful commodity corporations in the world across the sectors of mining, oil and natural gas.

Particularly damaging to foreign corporate interests and agendas was Magufuli’s targeting of the foreign-dominated mining sector in Tanzania, which contains some of the world’s largest deposits of minerals essential to 4th industrial revolution-related technologies. With 500,000 tonnes of nickel, 75,000 tonnes of copper, and 45,000 tonnes of cobalt, Tanzania sits on a mountain of mineral wealth and, more specifically, minerals needed for next-generation batteries and hardware that are themselves essential to the effort to rapidly implement “smart” infrastructure and automation globally. Within Africa, Tanzania has the continent’s second largest mining sector, second only to South Africa.

In the years prior to Magufuli’s rise, Tanzania had offered relatively low tax rates and little regulatory oversight for mining companies. Yet, in 2017, Magufuli declared “economic warfare” on foreign mining companies and his administration followed through on the declaration, passing two laws that provided the government with a much greater share of the revenue from the exploitation of Tanzania’s natural resources. This, of course, came at the expense of foreign mining conglomerates. The new legislation also gave the government the right to renegotiate and/or revoke existing mining licenses that had been awarded prior to Magufuli’s presidency.

Soon after, Tanzania’s government took aim at Acacia Mining, which is now owned by Canadian mining giant Barrick Gold, and slapped them with $190 billion in fines for unpaid taxes and penalties. “It shouldn’t happen that we have all this wealth, sit on it, while others come and benefit from it by cheating us,” Magufuli said of the decision. “We need investors, but not this kind of exploitation. We are supposed to share profits.” In 2018, the administration went after Acacia again, fining them $2.4 million for contaminating local water supplies in residential areas.

2018 was also the year that Magufuli’s biggest rift with powerful mining corporations took place, one that potentially influenced his disappearance and subsequent death. The Kabanga nickel project, the largest, development-ready nickel deposit in the world, had been owned jointly by Canada’s Barrick Gold and commodities giant Glencore. In May 2018, Magufuli’s administration revoked the Barrick-Glencore license for the project, along with several others that included other nickel, gold, silver, copper and rare earth mining projects.

Angering Glencore in particular is a risky business. The commodities giant was originally founded by Marc Rich, an infamous asset for Israel’s Mossad who allowed Glencore profits to be used to finance covert intelligence activities. Rich and Glencore’s intelligence ties are discussed in greater detail in Part IV of Whitney Webb’s series on the Jeffrey Epstein scandal. Today, Glencore is closely linked with Nat Rothschild, the son and heir of the scion of the British-based branch of the elite banking family, who purchased a $40 million stake in the company and was largely responsible for orchestrating Simon Murray’s appointment as Glencore’s chairman as well as his close relationship with Glencore CEO Ivan Glasenberg.

Then, in January 2021, a month before Magufuli disappeared, the Kabanga Nickel project went forward without Glencore and Barrick Gold, with Tanzania successfully negotiating joint ownership of the mine with a company set up by Norwegian millionaire Peter Smedvig and two of his associates. Unlike the Barrick-Glencore project, in which Tanzania’s government had no financial stake, the new project gave Tanzania a 16% ownership stake in the mine, which is now required by law following Magufuli’s reform of the country’s mining sector.

The loss of Kabanga was clearly a grave one for Barrick Gold and Glencore given the central role nickel and this specific deposit in Tanzania are set to play in the production and implementation of “smart” technologies. Nickel, among other uses, is a key component of the next-generation batteries used in “smart” technologies, specifically in electric vehicles. As a result, the demand for nickel is projected to rise dramatically in the next few years, in part due to the current effort to phase out most motor vehicles and replace them with ones that are both electric and self-driving. The importance of nickel to the so-called 4th Industrial Revolution has been underscored by the World Economic Forum, which estimates that demand for high-purity nickel for EV battery production “will increase by a factor of 24 in 2030 compared to 2018 levels.” In addition, last month, Tesla CEO Elon Musk said that “nickel is the biggest concern for electric car batteries.”

In addition to Tanzania’s valuable nickel reserves, it can be argued that Tanzania’s other most significant mineral wealth lies in its graphite reserves, which rank as the 5th largest in the world. In 2018, Oxford Business Group estimated that Tanzania would become one of the top three graphite producers on the planet. With the World Bank estimating that graphite demand will increase 500% in the next 30 years, Tanzania now holds a strong bargaining position in the global market. The global lithium-ion battery market is “expected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 13.0% from 2020 to 2027,” and these batteries usually require both nickel and graphite, both of which are plentiful under Tanzania. As Elon Musk has put it, “lithium-ion batteries should be called nickel graphite batteries.”

Last year, Musk had tweeted that “We will coup whoever we want! Deal with it,” in response to accusations that the US government had backed the 2019 coup in Bolivia so that Musk’s Tesla could acquire rights to the world’s largest lithium reserves, another mineral critical to electric vehicle battery production. A few months before Musk’s infamous tweet, the foreign minister of Bolivia’s coup government had written a letter to Musk that stated that “any corporation that you or your company can provide to our country will be gratefully welcomed” in relation to the country’s mining sector. These incidents underscore US empire’s current willingness to engage in regime change to ensure control of mineral deposits considered essential to emerging technologies and the 4th Industrial Revolution.

In the case of Tanzania, it is worth noting that Glencore, which had its ownership of the Kabanga nickel deposit revoked by Magufuli, is closely tied to the World Economic Forum and is part of the Forum’s Global Battery Alliance as well as its Mining and Metals Blockchain Initiative, both of which focus on supply chains for minerals deemed essential to the 4th Industrial Revolution. Also of interest is the fact that Tundu Lissu, the Magufuli government’s most vocal critic and a main source for all mainstream media Tanzania reporting, was formerly employed by the World Resources Institute (WRI), a US-based non-profit and “strategic partner” of the World Economic Forum. The WRI aims to build “clean energy markets” and “value supply chains,” supply chains which will inevitably depend on cheaply sourced raw materials like nickel, graphite, and cobalt.

The World Resource Institute has received no less than $7.1 million from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and, according to the WRI donor page, they’ve received no less than $750,000 from the West’s most powerful corporate actors including Shell, Citibank, The Rockefeller Foundation, Google, Microsoft, The Open Society Foundation, USAID, and the World Bank. Lissu praised news of Magufuli’s sudden death as a “relief” and an “opportunity for a new beginning” in Tanzania. Tellingly, he also spoke very positively of the country’s future under Magufuli’s Vice President and current President Samia Suhulu, suggesting that she will take the country in a direction very different than that of her predecessor.

Thabit Jacob, a Tanzanian academic at Denmark’s Roskilde University was quoted in UpStream as saying that Rostam Aziz — one of Tanzania’s wealthiest businessmen and ex-parliament member who had a major falling out with Magufuli over tax policy— could soon become a key player in the new government, “meaning big business will play a bigger role” in the country’s future. Rostam owns Caspian Mining, the single largest Tanzanian mining firm and a frequent contractor for Barrick Gold.

COVID-19 response met with foreign hostility

Under the Magufuli administration, Tanzania’s COVID-19 response policies ran counter to the international consensus, with the country declining to implement any major lockdowns or mask mandates. It should be noted that even the CFR relayed that these decisions had the democratic support of the masses, writing that “on-the-street sentiment suggests many Tanzanians agree with the government’s light-touch approach.”

Magufuli was also skeptical of adopting COVID-19 vaccines before they could be investigated and certified by Tanzania’s own experts, warning that they could pose safety concerns due to their rushed development. “The Ministry of Health should be careful, they should not hurry to try these vaccines without doing research … We should not be used as ‘guinea pigs’”, Magufuli had stated in January. “We are not yet satisfied that those vaccines have been clinically proven safe,” Tanzanian Health Minister Dr. Dorothy Gwajima later remarked at a news conference.

Magufuli refused to immediately agree to receive COVID-19 vaccines from COVAX, a public-private partnership between Gates’ GAVI and the World Health Organization which aims to deliver 270 million COVID vaccines – with 269 million of them being the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine – to the world “as soon as they’re available.” In recent weeks, major safety issues with the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine have been identified by national regulatory bodies across Europe and Asia and numerous countries have suspended its use.

However, such nuance regarding the safety of “vaccine aid” was absent from the now ubiquitous mainstream narrative of Magufuli being “anti-science.” That narrative was first established as early as May 2020, when Magufuli exposed the inaccuracy of imported PCR testing kits after a goat, a piece of fruit, and motor oil all received ‘positive’ test results from the supplied kits. “There is something happening … we should not accept that every aid is meant to be good for this nation,” he proclaimed in a national address.

After this address, Bloomberg called Magufuli the “COVID-denying president.” Foreign Policy went as far as to dub the President as “Denialist in Chief” and asked if he was even “more dangerous than COVID-19.” Magufuli became the Western press’s poster boy for “COVID denial” while Tanzania became “the country that’s rejecting the vaccine.”

However, in the months that followed May 2020, the accuracy of PCR testing kits have been called into question, not only by mainstream media, but also “authoritative” global health bodies like the World Health Organization, thereby validating Magufuli’s initial critique. In a story titled “Your Coronavirus Test Is Positive. Maybe It Shouldn’t Be”, the New York Times reported that the “standard [PCR] tests are diagnosing huge numbers of people who may be carrying relatively insignificant amounts of the virus. . . and are not likely contagious.”

In November 2020, a landmark court case in Portugal ruled that the PCR test used to diagnose COVID-19 was not fit for that purpose, ruling that “a single positive PCR test cannot be used as an effective diagnosis of infection.” In their ruling, judges Margarida Ramos de Almeida and Ana Paramés referred to a study by Jaafar et al., which found that the accuracy of some PCR tests was only about 3%, meaning up to 97% of positive results could be false positives.

By December 2020, the World Health Organization had confirmed that the PCR test was ripe for false positives, warning that they could easily lead to COVID-free individuals receiving positive test results. The position that PCR testing kits are unreliable is not new science, as a 2007 New York Times article titled “Faith in Quick Test Leads to Epidemic that Wasn’t” wrote that the sensitivity of PCR testing kits “makes false positives likely, and when hundreds or thousands of people are tested, false positives can make it seem like there is an epidemic.” In addition, large batches of PCR test kits in the early phase of the COVID-19 crisis were contaminated with COVID-19 prior to their use, which was later found to have significantly skewed the number of cases reported in the early phases of the pandemic in the US and beyond.

Numerous examples of vaccines with severe adverse effects being pushed onto the Tanzanian people, combined with the widely reported safety issues surrounding the AstraZeneca/ Oxford vaccine that Tanzania would receive through COVAX, make the Western media’s “anti-science” characterization of Magufuli particularly inappropriate. For example, as far back as 1977, studies published in The Lancet established that the risks of the diphtheria tetanus pertussis (DTP) vaccine are greater than the risks associated with contracting wild pertussis. After mounting evidence linking the drug to brain damage, seizures, and even death, the U.S. phased it out in the 1990s and replaced it with a safer version called DTaP. A 2017 study funded by the Danish government concluded that more African children were dying at the hands of the deadly DTP vaccine than by the diseases it prevented. Researchers examined data from Guinea Bissau and concluded that boys were dying at 3.9 times the rate of those who had not received the shot, while girls suffered almost 10 times (9.98) the death rate. GAVI, subsidized by USAID and the Gates Foundation, has dumped over $27 million worth of the dangerously outdated DTP vaccine onto the Tanzanian health system as of today.

Furthermore, as detailed by Unlimited Hangout in December, the developers of the Oxford vaccine (the vaccine Tanzania would receive under COVAX), are deeply entangled with the eugenics movement and engage in ethically questionable activities regarding the intersection of race and science to this day. In 2020, The Wellcome Trust, the research institute where both of the lead developers of the Oxford vaccine work, was accused by the University of Cape Town of illegally exploiting hundreds of Africans by stealing their DNA without consent.

Also concerning is the fact that more than 20 European countries have halted use of the Oxford/ AstraZeneca vaccine due to a possible link to blood clot disorders and strokes. Even the New York Times has questioned if the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine is a viable candidate, particularly for Africa. According to a Times article from February, South Africa halted use of the AstraZeneca-Oxford coronavirus vaccine after evidence emerged that the vaccine did not protect clinical trial volunteers from mild or moderate illness.”

A recent election victory “amid claims of fraud”

In October 2020, Magufuli was reelected to a second, five year term, this time gaining a resounding 84.39% of vote. At the time, the US government-funded outlet Voice of America (VOA) quoted one Tanzanian, Edward Mbise, who told the outlet that “[they] all expected [Magufuli] to win due to what he has done … he has accomplished so many things that you can’t even finish listing all of them.”

However, Tundu Lissu, the leader of Magufuli’s main opposition party, alleged that the election had been fraudulent, but provided no evidence. According to the same VOA article, Lissu called for “citizens [to] take action to ensure all election results are changed.”

Lissu’s accusations of fraud were widely reprinted by Western media despite the lack of evidence. A BBC article was titled “President Magufuli Wins Election Amid Fraud Claims.” The Guardian, funded heavily by the Gates Foundation, similarly claimed that “Tanzania’s President wins re-election Amid Claims of Fraud.” In the US, the New York Times published a story called, “As Tanzania’s President Wins a Second Term, Opposition Calls for Protests.”

Neither mention of Magufuli’s approval ratings nor quotes from actual Tanzanian people were anywhere to be found in these articles, details which had been plentiful in Western mainstream media coverage of his first election victory. Quotes that did appear were usually from Lissu, now exiled in Belgium, or other members of his party.

Not long after Lissu’s claims had been uncritically repeated by major Western media outlets, former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo announced sanctions on his last day in charge of the State Department that targeted Tanzanian officials who had allegedly been “responsible for or complicit in undermining the 2020 Tanzanian general election”. It is worth pointing out that the similarities between the election fraud accusations in Tanzania and those made in Bolivia just prior to the US-backed November 2019 coup are considerable.

Two weeks later, on February 5th, 2021, the Center for Strategic & International Studies suggested that the US might, as it often does, fund Magufuli’s political opposition, openly suggesting that the “the Biden administration has an opportunity to increase direct engagement with Tanzanian opposition politicians and civil society groups,” using Magufuli’s “dangerous” approach to COVID-19 as public justification.

That same week, the Guardian’s Global Development section (made possible through a partnership with The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation) published an article titled, “It’s time for Africa to rein in Tanzania’s anti-vaxxer president.” Predictably, this article, and others like it, sought to paint the African leader as a crazy conspiracy theorist, but left out the fact that Magufuli had earned his master’s and doctorate degrees in Chemistry before being elected president in 2015.

On March 9th, Tundu Lissu, the opposition leader formerly employed by the Washington-based and Wall Street-funded World Resource Institute, contended that Magufuli was critically ill with COVID-19. In a series of tweets, Lissu asserted that the then-president had been flown first to Kenya and then India to be treated for the virus. “We urge the government to come out publicly and say where is the president and what is his condition,” John Mnyika, another opposition leader, also publicly stated similar claims. The very first paper to run the story that Magufuli had COVID-19 was The Nation, a relatively new Kenyan newspaper that has received $4 million from the US-based Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Meanwhile, the Magufuli government repeatedly dismissed these claims as fake news. “He is fine and doing his responsibilities,” insisted Prime Minister Kassim Majaliwa on March 12. “A head of state is not a head of a jogging club who should always be around taking selfies,” Constitutional Affairs Minister Mwigulu Nchemba had said at the time.

On March 11, just days before the announcement of Magufuli’s death and Suhulu’s appointment to the post of President, the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), the influential think tank closely tied to the Rockefeller family and the US political elite, suggested that a “bold figure within the ruling party [i.e. Magufuli’s party] could capitalize on the current episode to gain popularity and begin to reverse course …”

While a swift leadership transition in Tanzania might seem like an unexpected surprise to western financial interests, groups in the US who specialize in foreign meddling and regime change operations had been at work in Tanzania ever since Magufuli’s initial election victory. The National Endowment for Democracy (NED), a US government think/do tank which aims to “support freedom around the world,” pumped $1.1 million into different Tanzanian opposition groups and causes over the last few years. One co-founder of NED, Allen Weinstein, once disclosed to the Washington Post that “A lot of what we do today was done covertly 25 years ago by the CIA.” Carl Gershman, NED’s other co-founder, once told the New York Times that “It would be terrible for democratic groups around the world to be seen as subsidized by the CIA . . .and that’s why the endowment was created.”

NED’s recent operations in Tanzania included projects to “organize young people to promote reform, and introduce them to new media tools that can assist in their efforts”, “recruit and train young artists to convey stories about governance”, financially support an opposition-friendly “satirical” news production that provides humorous commentary on current events to “encourage conversations”, as well as financially supporting the production of a “comprehensive televised civic education campaign” aimed at both COVID-related public awareness and “voter education.” The grantee for the funds, the Tanzania Bora Initiative, whose slogan is “transforming mindsets, influencing cultures” boasts of “empowering over 50 young Tanzanian political candidates.” The Tanzania Bora Initiative was also heavily supported by USAID while Magufuli was in office.

One wonders what effects these NED and USAID-funded efforts would have had on the country if Magufuli had not died in office. In January, the CIA-filled Jamestown Foundation began reporting on Tanzania’s “creeping radicalization issue” and eerily put forward the idea that “Tanzania could be primed to experience an increase in violence directed inward…” Though this thankfully never came to fruition, in other cases of Western-backed regime change, opposition groups funded by these same organizations have been known to stoke or create violence in order to justify Western intervention.

The Magufuli Administration wasn’t oblivious to the West’s regime change efforts. In the years following his election victory, Tanzanian police forces had raided meetings organized by the Open Society Foundations, a group infamous for their meddling initiatives in states targeted by the US’ foreign policy establishment.

Yet, despite his strong stands against the West, something about Magufuli’s approach had changed the day of his last public appearance on February 24th, 2021. That morning, the Tanzanian President had begun urging his countrymen to wear masks, something he had resisted doing for nearly a year after the WHO declared a pandemic, and urged them to begin taking health precautions.

A new President, to Western applause

Convenient for the powers that Magufuli had angered, his successor and VP, Samia Suluhu, hails from the United Nations’ World Food Programme and has a profile listed on the website of the World Economic Forum, suggesting a closeness with the circles her predecessor had rebuked. It still remains unclear if she has already reversed any of Magufuli’s policies, either economic or COVID-related, but some shifts seem likely given that her appointment has been met with pure celebration by the same institutional actors that actively worked to undermine President Magufuli.

Another potential indicator is the dubious discovery of a new COVID variant in Tanzania that reportedly has more mutations than any other variant. That variant’s discovery was announced just over a week following the announcement of Magufuli’s death and seems tailor-made to provide a public justification of a reversal of Tanzania’s government approach to COVID. Notably, the Tanzania variant was discovered by Krisp, “a scientific institute that carries out genetic testing for 10 African nations” that is funded by the Gates Foundation, the Wellcome Trust and the governments of the US, the UK and South Africa.

Regarding a potentially imminent reversal of Tanzania’s COVID policy, the reaction of the top official at the World Health Organization may offer a clue. WHO General Director Tedros Ghebreyesus had no time to comment after receiving word of Magufuli’s sudden death, but quickly took to Twitter minutes after Suluhu’s swearing-in ceremony to congratulate the country’s first female president, telling her that he’s “looking forward to working with her to keep people safe from COVID-19, and end the pandemic.” Ghebreyesus was previously on the board of two organizations that Bill Gates had founded, provided seed money for, and continues to fund to this day: GAVI and the Global Fund, where Tedros was chair of the board.

A few days before Ghebreyesus’ tweet, the State Department released a statement reaffirming the US’ commitment to supporting Tanzanians as they advocate for respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms and work to combat the COVID-19 pandemic, stating that “We hope that Tanzania can move forward on a democratic and prosperous path.” Vice President Kamala Harris had nothing to say in regards to the popular East African president suddenly dying, yet – like Ghebreyesus, she managed to send her best wishes to the newly sworn in Suluhu Samia on Twitter.

Billionaire-backed Human Rights Watch, whose revolving door with the US government is well documented, welcomed Magufuli’s death, publishing a piece entitled “Tanzania: President Magufuli’s Death Should Open New Chapter,” writing that the African leader’s sudden passing “provides an opportunity.” Notably, the same organization had supported the US-backed military coup in Bolivia as well as the Trump Administration’s regime change efforts in Nicaragua and had called for an increase of deadly U.S. sanctions on Venezeula’s Chavista government, even after the publication of a report by The Center for Economic and Policy Research which found that at least 40,000 Venezuelan civilians had already died due to the such sanctions.

Earlier this month, Judd Devermont, a former CIA senior political analyst on sub-Saharan Africa, in a CSIS piece titled “Will Magufuli’s Death Bring Real Change to Tanzania?,” wrote that, prior to Magufuli’s death, it was “believed that Suluhu was growing increasingly wary of Magufuli’s authoritarian policies. . .” Later in the article, the former CIA analyst accidentally disclosed his working definition of “authoritarianism” when he wrote: “Magufuli steered Tanzania toward authoritarianism by implementing a nationalist economic agenda characterized by stifled regional and international trade and a blow to foreign direct investment (FDI).”

However, the claim that Magufuli was against all foreign investment is misleading. Perhaps Devermont should have written that Magufuli’s policies were a blow to FDI from the West, as Magufuli, in the last months of his presidency and his life, was directly courting foreign investment from China.

In mid-December 2020, Tanzania Invests reported on a Magufuli meeting with Chinese leadership, after which Magufuli announced that Tanzania “welcomes traders and investors from China in various areas like manufacturing, tourism, construction, and trade for the benefit of both parties.” The report also noted that “Magufuli asked China to cooperate with Tanzania in investing in large projects by providing cheap loans” and that “Tanzania will further develop and enhance its long-standing relationship with China and will continue to support China on various international issues.” China is currently Tanzania’s top trading partner and Tanzania is the largest recipient of Chinese government aid in Africa. It is worth considering that this China pivot, particularly at a time when the US’ new Cold War with China is reaching new heights, played a role in Western-backed regime change efforts targeting Tanzania.

Looking beyond Tanzania

The fate suffered by President John Magufuli and Tanzania is similar to what happened in a neighboring country, Burundi, just six months ago. The president of Burundi, Pierre Nkurunziza, publicly refused to enact top-down mitigation measures in response to COVID-19, and was similarly vilified by US aligned press and think tanks. In May 2020, Nkurunziza expelled the World Health Organization from Burundi and, three weeks later, it was reported that he had died after suddenly going into cardiac arrest.

More recently, Zambia, which borders Tanzania and is set to hold elections this August, is currently angering some of the same actors that Magufuli had challenged in its government’s efforts to nationalize its copper mines and potentially other mining projects. In December, Zambian President Edgar Lungu announced that his government would acquire “a significant stake in some selected mine assets” in order to “create sufficient wealth for the nation.” Echoing Magufuli, Lungu had stated “We shall no longer tolerate mining investors who seek to [profit] from our God-given natural resources, leaving us with empty hands.”

In January, Lungu took a step towards nationalizing the copper mining sector after a protracted dispute with none other than Glencore. Copper, like nickel, graphite and lithium, is a metal critical to the success of the 4th Industrial Revolution. Western media reports on Lungu’s recent move quoted experts who urged Zambia’s government “to tread carefully” in its efforts to increase the role of the public sector in the nation’s mining industry.

Then, a week after Magufuli’s death was announced, Lungu’s main competitor in the upcoming election publicly accused Lungu of trying to have him murdered while some English language, pro-Western media outlets have already claimed that Lungu plans to rig the upcoming election in his favor and that the country “may burn” if the election has the “wrong” outcome.

Such examples reveal that the situation that has recently unfolded in Tanzania is hardly unique in today’s Africa. However, the domination of the media landscape with constant COVID coverage has made Western audiences largely unaware of the various regime change efforts that have taken place or are underway in the region. Unlike regime change efforts of the recent past, those targeting Africa, and also Bolivia, seem laser focused on mining assets deemed essential to establishing the supply chains needed to power the 4th Industrial Revolution.

With many of these countries having recently cozied up to China, it seems the regime change projects and proxy wars of the future are set to revolve, not around fossil fuels and pipelines, but over whether the East or the West will dominate the supplies of minerals needed to produce and maintain next-generation technology.

Not only has COVID kept reporting on these coups for minerals to a minimum, it has also lent a convenient cover for the demonization of leaders and the advancement of regime change in countries that are being targeted for other reasons that have everything to do with resources and little to do with a virus.

TheAltWorld

TheAltWorld

doug lowe

Denier only of FALSE science. Definitely a major threat to Empire.