Visionary, Creationism, and the Left Ideal

Following the publication of my article “Muhammad Iqbal, Eurasianity, and the Fourth Way”, one of my Pakistani friends drew my attention to the article “Iqbal’s Lenin” by Mahir Ali, published in Dawn on November 8th, 2017 and timed to commemorate both the 100th anniversary of the Revolution in Russia and the 140th birthday of this Pakistani philosopher. The latter article cites the thesis of Meem Sheen that Iqbal’s philosophy can be expressed with the words “Communism plus God”, citing as an example of such the poems “Lenin Khuda ke Huzoor Mein” (“Lenin in God’s Presence”) and “Farman-i-Khuda” (“God’s Command”). In addition, Mahir Ali drew attention to Iqbal’s interest in the Bolshevik experiment, which, indeed, has served as an inspiration for many authors, and remarked: “the recent excesses of globalised capitalism serve as an enduring reminder that Lenin’s ghost hasn’t lost its relevance.”

Upon reading this publication, the lines of the Russian poet Nikolai Klyuev, written in 1924, immediately came to my mind:

|

Есть в Ленине керженский дух, Игуменский окрик в декретах, Как будто истоки разрух Он ищет в «Поморских ответах»…

Борис, златоордный мурза, Трезвонит Иваном Великим, А Лениным – вихрь и гроза Причислены к ангельским ликам. |

There is in Lenin the Kerzhensky spirit, A hegumen’s shout in decrees, As if the origins of devastation He sought in the Pomeranian Replies…

Boris – Mirza of the Golden Horde Ringing through Ivan the Great And through Lenin – whirlwind and storm Numbered among angelic faces. |

It is difficult to explain why Nikolai Klyuev, and not other poets of the revolutionary era, such as Vladimir Mayakovsky, came to mind. Perhaps because, unlike the Silver Age authors, the modernists, and other groups and circles that existed during this critical period in 20th century Russia, Nikolai Klyuev’s works always bore a clearly pronounced religious (Orthodox Christian) character, albeit sometimes framed in terms of revolutionary pathos.

For example, in his poem “The Fourth Rome”, published in St. Petersburg in 1922, Klyuev celebrated the death of the Russian Empire:

|

Это я зловещей совою Влетел в Романовский дом, Чтоб связать возмездье с судьбою Неразрывным красным узлом… |

I am the sinister owl That flew into the Romanov’s house, To tie retribution with destiny With an unbreakable red knot… |

Considering the fact that in 1905-7 Klyuev was arrested on more than one occasion for agitating among peasants and refusing to serve in the army, the conclusion might be drawn that Klyuev was an agent of the Bolsheviks or sympathized with them. However, this is not the case. Nikolai Klyuev’s figure was contradictory and ambiguous. A vivid representative of peasant creativity and popular religious consciousness, a native of the Russian North, and a friend of Sergey Yesenin (some are even inclined to believe that Klyuev was his teacher), Klyuev was executed by firing squad in 1937 for “counter-revolutionary activity.” Officially, he was alleged to have participated in the “Union for the Salvation of Russia”, which never existed. In fact, Klyuev was shot because his works did not match the ideological guidelines of the ruling Communist Party. In the late 1920’s, Klyuev became disillusioned with Soviet power, and his works can be found to harbor criticism of the Bolshevik regime, especially of the collectivization of peasants, which would be the main reason for the repression of this poet.

In his poem “Pogorel’shchina” from 1928, Klyuev wrote:

|

Душа России, вся в огне, Летит по граду, чьи врата Под знаком чаши и креста. |

Russia’s soul, all on fire, Is flying through the castle, whose gates Bear the sign of the cup and the cross

|

In 1934, Klyuev published a cycle of poems entitled Devastation (Razrukha), one of whose verses reads:

|

То Беломорский смерть-канал, Его Акимушка копал, С Ветлуги Пров да тётка Фёкла. Великороссия промокла Под красным ливнем до костей И слёзы скрыла от людей, От глаз чужих в глухие топи… |

The White Sea death-canal, Dug by Akimushka, From Vetluga Prov and Auntie Tekla Great Russia was drenched To the bone by a red downpour She hid her tears from people, From the eyes of strangers in the thickets and bogs |

In 1932-1933, a significant swathe of the Soviet Union was hit by a drought which caused mass starvation (and this subject to this day remains the pretext of numerous political manipulations, often involving direct frauds, such as photos taken in other countries alleged to be images of famine victims in the USSR), and thus the appearance of the latter work was a quite provocative gesture on Klyuev’s part, one which could not go without consequences. The report of Klyuev’s interrogation over his attitude towards Soviet power records the following response:

“My views on Soviet reality and my attitude towards the policies of the Communist Party and Soviet power are determined by my reactionary religio-philosophical views. Hailing from a long line of an Old Believer family, tracing back on my mother’s side to Protopope Avvakum, I was raised in the Old Russian culture of Korsun, Kiev, and Novgorod, and I absorbed love for old, pre-Petrine Rus, of which I am a bard. The construction of socialism in the USSR under the dictatorship of the proletariat finally destroyed my dream of Ancient Rus. Hence my hostile attitude towards the Communist Party and Soviet power’s policies aimed at the socialist restructuring of the country. I consider the practical measures implemented to realize this policy to be violence by the state against the people, who are bleeding out in fiery pain.”

Nikolai Klyuev was rehabilitated in 1957.

This digression into the tragedy of the Russian Revolution and the Red Terror is necessary to clarify the relationship between power in its various metamorphoses and those people who belong to the ranks of visionaries, such as Nikolai Klyuev and Muhammad Iqbal. In Klyuev’s case, the elements raged in front of his very eyes, rendering him an eyewitness, whereas Iqbal assessed the situation from the outside, on the basis of scarce information and reports in the press, in which reality was silenced by propaganda and communist censorship or distorted by foreign media for political ends.

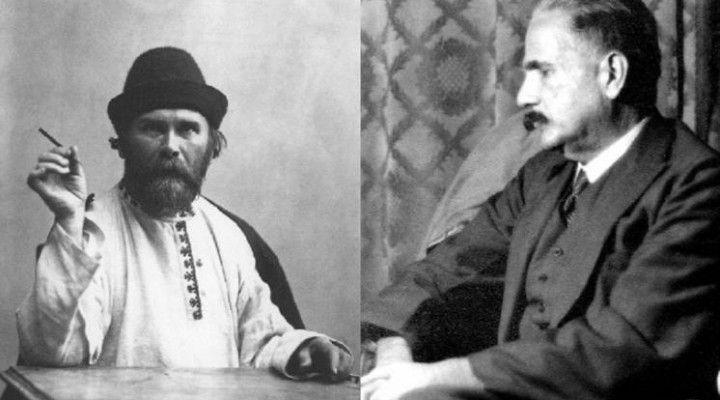

Yet both poets were united by two central themes in their work: a strict adherence to the creationist tradition (Christianity and Islam), and the celebration of oppressed social groups, such as the poor and toilers.

Muhammad Iqbal’s “Message of the East” was translated into Russian as early as 1923, in the year following its initial publication, and his “Allegories of Self-Denial” was published in Russia in the same year as it was in British India, in 1918. Translations of other works were later published in the USSR in the 1930s. It is unknown whether the top leadership of the Soviet Union was familiar with Muhammad Iqbal’s works, but the very fact of their publication almost immediately after the Revolution, and then again in the 1960s, suggests that Iqbal was seen in the USSR as a theoretician of national liberation struggle and revolutionary romanticism. Soviet commentators on Iqbal’s works considered him to be a progressive thinker who stood on anti-imperialist positions and for serving society and the people. Given the friendly relations between the USSR and India, however, pretexts for criticism were found as well. For example, the foreword to an anthology of Iqbal’s poetry published in 1964 reads: “Iqbal the politician, in his later period of activism, supported the reactionary separatist current in the Muslim communal movement, which was instrumentalized by the colonizers to divide India’s national forces…he stood against materialist ideology, instead advocating the adaptation of Islam to the needs of modern society.” Such an interpretation and deliberate concealment of historical facts was typical of Soviet censorship of the period, when the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the USSR was Nikita Khrushchev, known for his fierce anti-religious offensives. In the Soviet period, thus, Iqbal was popular as a poet and philosopher, but Iqbal the politician was considered to be of limited value.

Yet history has shown that it was not Iqbal, but Marxist-Communist ideology that was in fact limited.

If the Bolsheviks really had relied on the popular masses, they would not have destroyed churches and there would not have been the anti-religious persecution from which both Christian and Muslim believers suffered in Russia. The latter mistake, however, would not be understood until decades later. Moreover, Marxism does not wield a monopoly on the idea of justice, which is also addressed in both Christianity and Islam. Rather, Marxism has used the ideas of the creationist worldview, transforming them to suit the needs of certain political forces. The activism of these forces’ followers in the contemporary West shows their deep degradation. For instance, all Communist parties in Europe supported the NATO bombing of Libya in 2011, and so-called Cultural Marxism is not only limited in its understanding of the historical process, but has also in practice found expression in the institutionalization of promiscuity and connivance. This itself points towards the continued relevance of Muhammad Iqbal’s call for moral betterment.

https://www.geopolitica.ru/en/article/visionary-creationism-and-left-ideal

TheAltWorld

TheAltWorld

0 thoughts on “Visionary, Creationism, and the Left Ideal”