The US Military Around The World

It is the Pentagon’s mission to move from physical presence to sophisticated online operations in the near future. And, for America’s military and political communities, March proved rather fruitful when it came to various doctrines and strategies.

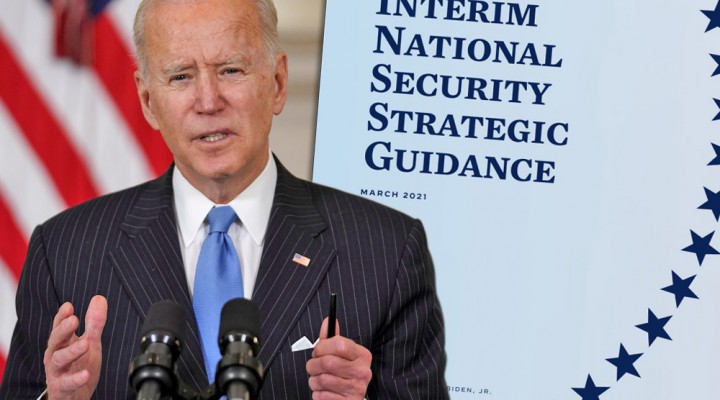

At the start of March, the Interim National Security Strategic Guidance was released on the initiative of the White House. The document has been prepared to guide all actions related to the strategic vision for US defence and security. That is, it directly concerns the military bloc and the intelligence community.

The weaknesses were noticed immediately. For example, retired Lieutenant General Thomas Spoehr, now director of the Heritage Foundation’s Center for National Security, noted that the guidance contains “some puzzling thoughts”. The document states that defence spending will be cut, especially the section on modernising America’s nuclear arsenal. In fact, it says that the US will reduce the role of nuclear weapons in its national security strategy. But during his confirmation hearing before Congress, Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin said that nuclear deterrence is the “DOD’s highest priority mission”.

Biden’s new strategy identifies the highest priority as investment in people, so training military personnel rather than replacing the nuclear arsenal and similar initiatives.

Another inconsistency is the statement that the US will avoid “forever wars” that cost trillions of dollars and thousands of lives. Biden has already shown himself to be a proponent of military adventurism by issuing orders to strike targets in Syria. It is unlikely he’ll be able to withstand the continued remonstrances of his advisers, who will be able to convince him to protect American interests, no matter where they may be.

It is telling that the main priorities are the same as in Trump’s strategies – Russia, China, North Korea and Iran are identified as representing the biggest threat. But while Trump said that the US would not interfere in the affairs of other countries, Biden has returned to the Democrats’ more traditional method – advancing democratic values around the world. This should probably be seen as a desire to carry out another series of colour revolutions adapted to the world today, as well as to exert pressure through pro-American alliances such as NATO.

When it comes to regions, emphasis has been placed on Europe, the Western Hemisphere, and the Asia-Pacific Region. The countries with whom the US intends to expand its partnerships are the UK, Canada, Mexico, India, Vietnam, Singapore, New Zealand, and the ASEAN member states.

As well as ideas for spreading democracy, a fairly significant proportion of the document covers new technologies, particularly cyberspace and 5G. It is possible to conclude from this that the new administration will intensify its use of cyber operations as a non-kinetic means of warfare. It is no coincidence that all the accusations of cyberattacks under Biden are directed at Russia, and it has even been publicly stated that the US will retaliate.

It will probably be around a year before a full national security strategy is released and a similar one covering US defence. For now, Biden is trying to establish his priorities in order to send a message to both the US authorities and other states.

On 16 March, the US Army issued a new strategy entitled “Army Multi-Domain Transformation. Ready to Win in Competition and Conflict”.

This document is also of considerable interest. It talks about expanding the presence of US ground troops around the globe and notes: “In the Indo-Pacific, 24 of 29 armed forces chiefs are army officers, and of the 30 NATO member states, 22 have armed forces chiefs from their respective armies. Through this professional kinship, the U.S. Army can play an outsized role in supporting U.S. inter-agency objectives in a whole-of-government approach.” This principle of “soft power” within “hard power” has long been used by the US military to draw partners from other countries into its zone of influence.

Commenting on the new strategy, the Chief of Staff of the US Army, General James McConville, noted that non-military warfare methods are in great demand these days. According to McConville, “Narrative competition is the constant worldwide struggle for the hearts and minds of a myriad of different audiences in different nations. It’s the fight o [sic] tell America’s story and burnish its reputation when adversaries are trying to smear and misinform. Everything the Army does that isn’t secret contributes to the national reputation for good or ill … Insensitive or unethical acts that accomplish the mission today might do lasting reputational damage that every other unit has to deal with down the road.”

He explains that direct and indirect competition are defined by whether the US is willing to switch to the use of armed force or not. Essentially, “direct” competition is any situation where policymakers are willing to see American troops kill foreign citizens. Indirect competition, on the other hand, means that the US does not intend to use lethal force, although open fighting by allies, partners and proxies is definitely a possibility here. Thus, providing Afghan rebels with Stinger missiles against the USSR was indirect conflict, even though people died, while deploying a combat brigade to the territory of a threatened ally is direct conflict because there is the potential for a clash between US and foreign forces.

There is a clear hint here at how the US will behave towards China (including support for Taiwan), as well as towards Russia and Iran.

The article also talks about how to win over countries that have good relations with potential enemies. It says: “The most common of these [situations] are the many instances where the United States and an adversary both have sustained relations or presence. This is one of the significant differences between current great power competition and the Cold War. Today, even some of the United States’ closest, most long-standing allies have significant relations with adversaries.

The article also talks about how to win over countries that have good relations with potential enemies. It says: “The most common of these [situations] are the many instances where the United States and an adversary both have sustained relations or presence. This is one of the significant differences between current great power competition and the Cold War. Today, even some of the United States’ closest, most long-standing allies have significant relations with adversaries.

“Debates within the governments of even some of our closest allies as to whether to privilege security and ties with the United States or economics and China in relation to information technology infrastructure are examples of how indirect competition occurs virtually everywhere….

“In any given country, both great powers will be conducting military-to-military exchanges, providing technical assistance, hosting students for military education and training, building security force capacity, selling equipment, or procuring goods and services from the local populace….. The partner is happy to send students to the war colleges of both great powers or to buy equipment from both.”

And, in order to win partners over for good, the US military suggests undermining the reputations of those countries identified as competitors. “A good reputation is a strategic asset: Narrative competition…is reflected in the rise and fall of a country’s reputation based on general perceptions of its strength, reliability, and resolve. Narrative competition is on-going, open-ended, and larger than any single event or issue. It is the connection linking multiple subordinate instances of competition over specific issues into the larger whole.

“Narrative competition is enduring and cumulative; the reputation of the United States accumulates over time….. Despite this power, narrative competition only goes so far. The United States could be preeminent in global reputation, yet still be unable to effectively compete for a specific issue because it has not built the relationships, lacks presence, or simply does not have capabilities relevant to the situation.”

There are also plans to carry out asymmetric actions with an emphasis on America’s prevailing image as the defender of democracy. “To the extent that open democratic systems and values put the United States at a disadvantage in what is sometimes called political warfare, those same characteristics make the United States a more attractive partner. If the adversary employs competition below armed conflict by means such as harassing fishermen in disputed zones or conducting disinformation campaigns, the best response for the Joint Force might not be to attempt to respond symmetrically with some similar form of aggression. An adversary’s aggressive actions create the possibility of an asymmetric response, in which the threatened ally or partner is eager for deeper cooperation with the United States.”

The focus of new documents like these is being verbally confirmed by other high-ranking military personnel at the official level.

At a US Senate hearing on 25 March 2021, Acting Assistant Secretary of Defense for Special Operations and Low-Intensity Conflict Christopher Maier stated that “the SOF community continues to make progress in adapting its capabilities to the challenge of great-power competition with Russia and China.”

General Richard Clarke, commander of the Pentagon’s Special Operations Forces (SOF), reported that there are 5,000 special operations forces in 62 countries. They carry out joint actions with partners from other countries, and inter-agency work is underway to uncover transregional networks, prevent acts of terrorism, track financial operations, and so on.

The SOF will play a central role in opposing China and Russia in the future. They will “coordinate MISO conducted via the internet and actively engage foreign audiences to expose, counter, and compete with hostile propaganda and disinformation online.

“In 2021, we will incorporate our first foreign partners and interagency liaisons… Finally, we are grateful for a range of authorities granted by Congress that allow SOF to have outsized impact across multiple mission sets. Operations conducted under 10 USC § 127e (CT) provide flexible options to apply CT pressure in otherwise inaccessible or contested areas, and operations under FY18 NDAA § 1202 (Irregular Warfare) are essential for applying SOF capabilities to illuminate and impose cost on malign actors. Additionally, authorities under 10 USC § 127f (Intelligence / Counter-Intelligence) and FY20 NDAA § 1057 (Clandestine Operational Preparation of the Environment) replaced the Emergency and Extraordinary Expense authorization allowing application of SOF capability with greater efficiency and transparency.”

This means that US lawmakers have given the go-ahead to expand the range of all kinds of covert operations aimed at violating the sovereignty of other countries, while competing with propaganda means a vast arsenal of information operations from tarnishing Russia’s image on the world stage to using bots and trolls in online activity.

Digital transformation and the introduction of artificial intelligence is on the agenda of US special forces, too.

Paul Nakasone, the commander of US Cyber Command, also spoke before the Senate on 25 March. He said: “Russia is a sophisticated cyber adversary. It has demonstrated its ability to conduct powerful influence campaigns utilizing the medium of social media. Moscow conducts effective cyber-espionage and other operations and has integrated cyber activities into its military and national strategy. Despite public exposure and indictments of Russian cyber actors, Russia remains focused on shaping the global narrative and exploiting American networks and cyber systems.”

Nakasone presented his agency’s formidable agenda for 2021.

Given the US military’s preparations for more decisive action and its biased attitude towards other countries, there is really little point in hoping for a normalisation of relations between the US and Russia.

https://orientalreview.org/2021/04/05/the-us-military-around-the-world/

TheAltWorld

TheAltWorld

0 thoughts on “The US Military Around The World”