How a Mass Bot Network is Pushing the Coup in Bolivia

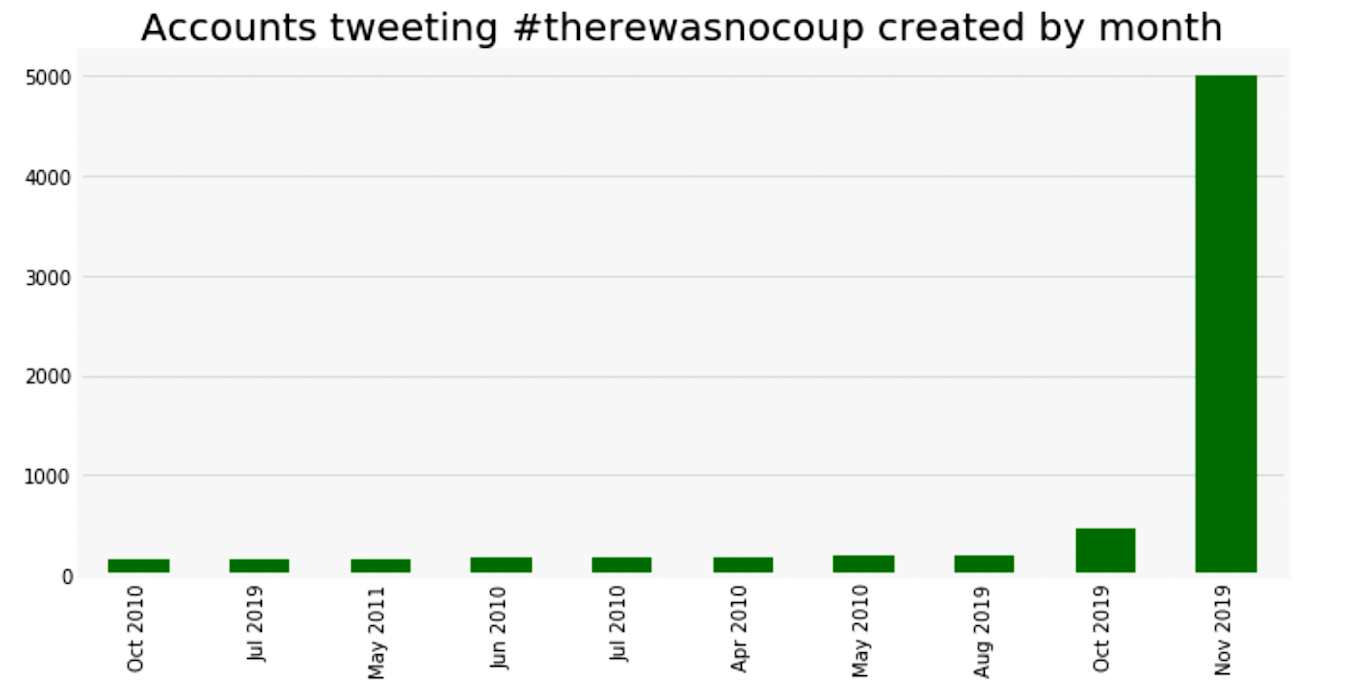

New research found that, of the 17,427 accounts studied using anti-Morales hashtag #BoliviaNoHayGolpe, almost a third were created on November 11, the day of the coup.

MPN– Bolivia. November 11. Generals appear on television demanding the immediate resignation of the elected head of state, Evo Morales. Ever since Morales won the October 20 election, the country had been in upheaval. The right-wing Bolivian opposition claimed that the socialist had won by foul means, an accusation repeated by the Organization of American States. All over Bolivia, the opposition attempted to intimidate or terrorize the government into submission. For example, the Mayor of Vinto, Patricia Arce, was kidnapped, tied up, had her hair shaved off, covered in paint and dragged through the streets as she was physically and verbally abused. It seemed like a classic Latin America-style coup in the U.S.’ backyard.

But on social media, it was a different story. Twitter was full of tweets in both English and Spanish using the #BoliviaNoHayGolpe hashtag, the English translation being “there is no coup in Bolivia.” New research from First Draft News, a non-profit outlet specializing in highlighting and fighting misinformation, found that, of the 17,427 accounts using the anti-Morales hashtag, almost a third were created on November 11, the day of the coup.

A graph by First Draft shows that a large number of the accounts tweeting about the situation in Bolivia were recently created

First Draft’s research did not go far as identifying whether individual users were indeed bots or not; claiming it was “certainly suspicious” but unproven. However, the irregular phenomenon was immediately recognized at the time by journalists covering the events.

https://twitter.com/redfishstream/status/1194261063115722752?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E1194261063115722752&ref_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.mintpressnews.com%2Fhow-mass-bot-network-coup-bolivia%2F263122%2F

Good morning to all the Bolivia coup-bots.

I personally think Alejandro5283 made some good points about letting Bolivia military seize power, but Benicio85964, who offers a coupon for discount Uber ride, is wrong that this coup is better than the one the US backed in 1989. pic.twitter.com/ETOrLUQZzw

— Kevin Gosztola (@kgosztola) November 11, 2019

https://twitter.com/camilateleSUR/status/1193337568521281536?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E1193337568521281536&ref_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.mintpressnews.com%2Fhow-mass-bot-network-coup-bolivia%2F263122%2F

“Hahaha yet another Bolivia coup bot account which only has 4 tweets, all attacking me. It was created 3 hours ago, and it follows 1 person: far-right Bolivian coup leader Camacho. This pro-coup bot disinformation campaign is so obvious,” remarked Ben Norton of The Grayzone. Many of the new users featured a first name followed by a string of numbers, a classic machine-generated template for bots. Norton went so far as to make a collage of suspicious users’ tweets, all of which followed the first name number string template.

There are thousands of what are obviously bot accounts trolling anyone who tweets about the right-wing coup in Bolivia

They are spreading propaganda in English, their account names are often @ namenumbers, and they were created in November

There's a big operation going on here pic.twitter.com/GLJ8Sw14pM

— Ben Norton (@BenjaminNorton) November 11, 2019

Controlling the message is crucial in shaping public understanding and opinion on any issue or event. People are far more likely to support a “revolution” or an “uprising” than a “coup.” And “advanced interrogation techniques” are much more palatable than “torture”.

Corporate media across the political spectrum refrained from using the word “coup” to describe the events in Bolivia. For example, Time presented it as a “resignation” amid “protests” and “fraud allegations,” implying that it was Morales’ supposed election misdealings that led to his downfall rather than an orchestrated plan from the military. The U.S. government also lent its full support to the coup, stating the events constituted the “preservation of democracy” and claiming that “We are now one step closer to a completely democratic, prosperous, and free Western Hemisphere.”

Washington knows the value of controlling the message online. For example, the U.S. government’s regime change organization, USAid, secretly created a Cuban social media app called ZunZuneo, often described as Cuba’s Twitter. At its peak, it had 40,000 Cuban users (a very large number for the famously Internet-sparse island) who were unaware that the app had been secretly designed and marketed to them by the U.S. government in order to overthrow their government. The point was to create a great service that would slowly start to feed Cubans regime propaganda and direct them to protests and “smart mobs” aimed at triggering a color-style revolution.

On November 11 the #BoliviaNoHayGolpe hashtag trended in Virginia, home of a large Bolivian ex-pat community, but also of the CIA and other U.S. government organizations, leading to suspicion among many that the viral moment was not completely organic.

Another group that uses Twitter bots to foment regime change is the Venezuelan opposition, who attempted another coup against the government of Nicolas Maduro last month. Bolivia’s new President Jeanine Añez immediately recognized opposition politician and coup leader Juan Guaidó as Venezuela’s legitimate leader. An academic paper published by Cornell University found that bot platforms generated almost 7% of the retweets of tweets coming from the account of Venezuelan opposition leader Leopoldo Lopez and that opposition figures were far more supported by bots than government representatives.

After three fractious weeks attempting to maintain control, it appears that Bolivia’s right-wing opposition has succeeded in its attempts to seize power for the first time since 2006. Morales has fled to Mexico and the new government has rounded up and imprisoned or killed much of the domestic opposition. Crucial to that is controlling the media, forcing critical outlets like RT and TeleSUR off the air while detaining and imprisoned independent media journalists. But dominating social media necessitates alternative strategies. Modern problems require modern solutions.

TheAltWorld

TheAltWorld

0 thoughts on “How a Mass Bot Network is Pushing the Coup in Bolivia”