The Russian SMO (1): was it an Imperial intervention?

In this article, Tim Anderson completely scrutinizes Russia’s Special Military Operation and analyzes it: what led to the Russian SMO? was it justified as a measure of self-defence? and, most importantly, was Russia’s SMO an imperial intervention?

“Many experts call [the SMO of Feb 24, 2022] a turning point in world history, and some saw it as Russia becoming the military spearhead of the ‘Global South’ in the fight against the fading world order based on the destructive hegemony of the West” (Sadygzade 2024).

A remarkable consequence of the Russian Special Military Operation (SMO) in South East Ukraine was that, while it initially attracted very little international approval (UN 2022), within quite a short time, most of the world – and virtually all the global south – rallied to Russia and to BRICS, marking the beginnings of a major turnaround in global relations.

How was this possible when it is precisely the global south which has been the strongest anti-intervention group, opposing breaches of state sovereignty after a long history of Western invasions, coups and other interventions? If the Russian SMO were just another imperial intervention, like the 2003 invasion of Iraq, would this not undermine the promise of any new supposedly counter-hegemonic world order which included Russia?

To address that question we need a background which examines some distinct though inter-related questions: what led to the Russian SMO? was it justified as a measure of self-defence? and, most importantly, was Russia’s SMO an imperial intervention?

After examining those three questions in this article I will return to the turnaround issue, in a second part. This article is structured in these sections:

- NATO expansion,

- the Kiev coup, Crimea and the Donbass,

- the Question of Self-Defence and

- An Imperial Intervention, as in Iraq?

1. NATO Expansion

To properly understand the Russian Special Military Operation (SMO) in SE Ukraine we should have regard to NATO expansion, the 2014 coup in Kiev, the subsequent war against the mostly Russian people of the Donbass region, the status of Crimea, attempts to resolve the conflict through the Minsk Peace Treaties, and then the character of the 2022 invasion.

Only the very naïve imagined that this war began in February 2022. Even parts of the pro-NATO media reflected on that group’s responsibility for the conflict. Galen Carpenter (2022) wrote in the British Guardian:

“NATO’s arrogant, tone deaf policy towards Russia had contributed heavily to the Ukraine war … Analysts committed to a US foreign policy of realism and restraint have warned for more than a quarter century that continuing to expand the most powerful military alliance in history toward another major power would not end well” (Galen Carpenter 2022).

Despite Washington’s repeated mantra that Russia’s intervention was an “unprovoked war of aggression” (VOA 2023) even mild-mannered Pope Francis observed, more than once, that NATO had “somehow provoked” Moscow’s intervention (Albanese 2022).

The Ukrainian government in Kiev turned seriously anti-Russian after the US-backed 2014 coup and, after several massacres, there was a serious alienation from Kiev of the Russian speaking people in Crimea and much of south and eastern Ukraine. The formerly autonomous republic of Crimea quickly voted for secession from Ukraine and union with the Russian Federation, while two of the Donbass provinces (Donetsk and Luhansk) declared their own independence. There followed eight years of assaults by Kiev forces on the breakaway peoples of the Donbass.

Washington trained and armed Ukrainian troops for an attempt to reincorporate the alienated Donbass region and perhaps even to retake Crimea. There were talks and agreements for Kiev to properly address the autonomy concerns of the Donbass region. However former German leader Angela Merkel would later admit that these Minsk Accords were merely a ploy to gain time to build up the Ukraine military (Novaya Gazeta Europe 2023), while several in Washington soon announced their broader aim of weakening and eventually dismantling the Russian Federation, affirming Russia’s worst fears.

As the Soviet Union collapsed, over 1989-1991, the last Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev – looking to dismantle the Warsaw Pact alliance – sought assurances from NATO leaders that the Western bloc would not expand eastwards. The most famous assurance was that of US Secretary of State James Baker: “not one inch eastward”, to Gorbachev on 9 February 1990; but that was “only part of a cascade of similar assurances”, from “Baker, Bush, Genscher, Kohl, Gates, Mitterrand, Thatcher, Hurd, Major and Woerner” (NATOWatch 2018; NSA 2017).

It was all deceit. There have even been denials (including under the guise of ‘fact checking’) that such assurances were ever made (Pifer 2014; McCarthy 2022), or that Russia was even the target of a NATO ‘missile shield’ placement, which was said to be “purely defensive” (Reuters 2007; CNN 2008). A pretence was made there was some threat other than Russia, perhaps Iran (Sankaran 2024), but Russia did not take this seriously.

Faced with a wall of obfuscation, Russia had to assess the threat from NATO by actions, not just words. Yet Moscow was cautious, and continued for many years to speak of cooperation with “our Western partners” (Wheatley 2015), even as BRICS was created and as Russia entered Syria to fight Western-backed terrorist groups (Anderson 2019; Ch 7); yet in Syria, Russia shared the same stated objectives as the USA of ‘fighting terrorism’. In practice the two were engaged in a phony war, with Washington relying mainly on those same terrorists as its proxy militia. However, with the collapse of the Soviet Union, the basis for an ideological war was gone.

In the 1990s, while recognising that it could “alienate” Russia, US official Richard Haas summed up the arguments for NATO expansion as to “lock in the dividends of the Cold War’s end and greatly diminish the odds that this region will again become a battlefield … provide a reassuring anchor to these newly independent democracies … [and] help eliminate a potentially destabilizing power vacuum in Europe” (Haas 1997). In practice, NATO expanded from 12 member states in 1948 to 31 by 2022. This was through what is described as an “open door policy”, where European states (in some supposedly liberal manner) could voluntarily “choose” to join the military bloc (NATO 2023).

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact, NATO “invited Czechia, Hungary and Poland to begin accession talks” in 1997. These three became “the first former members of the Warsaw Pact to join NATO in 1999.” (NATO 2023). After that “Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia were invited and actually joined NATO in 2004.” Albania and Croatia joined NATO in 2009; Montenegro in June 2017; and the Republic of North Macedonia in March 2020 (NATO 2023).

The problems from Russia’s point of view became more acute when it came to the border countries of Georgia and Ukraine. The last “friendly warning from Russia” that NATO “needed to back off” came in March 2007, when Putin addressed the Munich Security Conference. “NATO has put its frontline forces on our borders”, Putin complained, and that “represents a serious provocation that reduces the level of mutual trust … against whom is this expansion intended? and what happened to the assurances our Western partners made after the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact?” (Galen Carpenter 2022). As recently as 2021, Russia demanded that NATO retract its pledge to admit Ukraine and Georgia” (FT 2021). Georgia and Ukraine could provide a border base for nuclear missiles aimed at Russia, something the US itself did not tolerate in 1962 when Soviet nuclear missiles were placed in Cuba to defend the independent island from a second invasion.

Even Robert M. Gates, Secretary of Defence under Bush (the Second) and Obama said relations with Russia had been “mismanaged … US agreements with the Romanian and Bulgarian governments to rotate troops through bases in those countries was a needless provocation … trying to bring Georgia and Ukraine into NATO was truly overreaching … recklessly ignoring what the Russians considered their own vital interests” (Galen Carpenter 2022). One Western observer said “It was entirely predictable that NATO expansion would ultimately lead to a tragic, perhaps violent, breach of relations with Moscow. We are now paying the price for the US foreign policy establishment’s myopia and arrogance” (Galen Carpenter 2022).

After the SMO, NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg recognised that President Putin “went to war to prevent NATO, more NATO, close to his borders. [yet] He has got the exact opposite” (Stoltenberg 2023). It is very clear then that Russia felt threatened by NATO expansion and acted to avert that threat.

2. The Kiev coup, Crimea and the Donbass

In 2014, Washington backed a bloody coup in the capital. As key Washington official Victoria Nuland said, just months before the coup, “We’ve invested over $5 billion to assist Ukraine in these and other goals that will ensure a secure and prosperous and democratic Ukraine” (Nuland 2013).

In its customary fashion, Washington denied responsibility for the coup. But the new regime sharply reoriented Ukraine from the East to the West. The Ukrainian state was radically changed after a bloody insurrection in the capital, driving elected President Yanukovych into exile and mobilising neo-Nazi groups which were violently anti-Russian. As the pro-NATO media reported, the neo-Nazi Azov Brigade fighters “are Ukraine’s greatest weapon and may be its greatest threat” (Walker 2014), due to their extremism.

Massacres of left and pro-Russian Ukrainians began, including the infamous and horrific Odessa massacre of May 2014, where dozens of leftists were slaughtered in and around Odessa’s House of Trade Unions (Azərbaycan24 2022), and which Wikipedia (2023) now misleadingly calls “Odessa clashes’. A good overview of this period is provided by the 2016 documentary ‘Ukraine on Fire’ (Lopatonok and Stone 2016). The extreme right factions successfully urged rehabilitation (in street names and statues) of Stepan Bandera, (Portnov 2016), the notorious ultra-nationalist and Nazi collaborator who had helped lead the mass murders of Russian, Polish, Roma and Jewish people in Ukraine, in the 1940s (Glöckner 2021).

In reaction to the coup and the neo-Nazi-led massacres, the Russian speaking peoples of SE Ukraine (the Donbass) began to defend themselves by excluding Kiev regime officials and military from as much of the region as they could. Autonomous administrations were set up which received support from Russia and, after that, Kiev declared war. In November 2014, referring to the siege of the Donbass, former President Poroshenko infamously said:

“We will have jobs – they will not. We will have our pensions – they will not. We will have care for children, for people and retirees – they will not. Our children will go to schools and kindergartens – theirs will hole up in basements … that is exactly how we will win this war” (Slavyangrad 2014).

By late 2014, Kiev regarded itself at war with the self-declared autonomous republics of the Donbass (the Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics). There was bombardment of these regions, and defence by the DPR and LPR militia, with some logistical support from Russia.

The UN in Ukraine (OHCHR 2022) estimates that, in this Donbass war (between the 2014 Kiev coup and the Feb 2022 Russian SMO), more than 14,200 were killed and 37-39,000 injured, more than two thirds of those comprising Donbass militia and civilians.

The people of Crimea, who had an autonomous status under Ukraine, similarly could not tolerate the post-coup regime. Popular feeling coincided with Russia’s wish to not lose its main Black Sea port, which it had maintained under an agreement with pre-2014 Kiev. The last thing Russia wanted was to lose Sevastopol, which it had defended from Nazi Germany, and let it fall into the hands of a neo-Nazi linked regime embedded with NATO. As it happened, the population of autonomous Crimea also preferred Russian status.

As Russian Foreign Affairs put it, Crimea was “reunited with the Motherland by popular vote in 2014” (MFA 2022). The 16 March 2014 vote was extremely high for incorporation: “97% of voters in Crimea and 95.6% in the city of Sevastopol voted for the peninsula’s reunification with Russia. The Republic of Crimea and the federal city of Sevastopol became parts of Russia on March 18, 2014.” (BBC 2014a). Western politicians tried to dismiss the official poll as coerced, but subsequent Western polls reproduced similar figures. A June 2014 Gallup poll “asked Crimeans if the results in the March 16, 2014 referendum to secede from Ukraine reflected the views of the people”. A total of 82.8% said yes. When broken down by ethnicity, 93.6% of Crimean Russians said they believed the vote to secede was legitimate, while 68.4% of Crimean Ukrainians felt so (Rapoza 2015). There is a long and complicated story behind the shuffling of the “autonomous republic” of Crimea between Russia and Ukraine within the Soviet Union (see Lavrenin 2022; Kramer 2014); this included the fight of the Crimean Tartars to return to the land from which they were deported in 1944 (Wydra 2003: 111). For the purpose of this article, it is sufficient to recognise the strong popular support in Crimea for union with Russia.

Relatively early in the Donbass war, peace talks were brokered in Minsk, the Belarus capital. These talks sought to establish a ceasefire between Kiev forces and the self-proclaimed Donbass republics, a prisoner exchange and a military withdrawal, combined with a commitment by the Ukrainian government to restore control over its eastern border and hold local elections in the occupied territories; some sort of autonomous Donbass would then be reintegrated as part of Ukraine (Peacemaker 2015). France and Germany signed onto specific measures to implement this agreement, and the “Minsk 2” agreement was counter signed in February 2015 by representatives from the Russia, Ukraine, the DPR and LPR (Allen 2020).

However, most of this agreement was not implemented, while some NATO linked writers (e.g. Allen 2020) denounced the agreement as a violation of Ukraine sovereignty, even though it had been signed by Ukrainian president Poroshenko. Much later, former German chancellor Angela Merkel acknowledged that, while initiating the NATO membership of Ukraine and Georgia in 2008 was wrong, the Minsk agreements were “an attempt to give Ukraine time to develop” (Novaya Gazeta Europe 2023); an expression which Russia immediately interpreted as giving Ukraine time to build up its military and then seize the Donbass by force (TASS 2023).

Indeed, after 2014, US and NATO officials were busily building up the military capacity of Kiev forces, specifically to fight Russia. John McCain and Lindsey Graham – US senators who had previously helped arm proxy militia to be used against Libya and Syria (Sink 2012) – urged US President Obama to “provide arms to Ukrainian forces, who are trying to ward off a renewed invasion threat by Russian forces” (Wong 2014). By 2016 there was a US-led “Joint Multinational Training Group-Ukraine [JMTGU] … to help build the training capacity of the Ukrainian land forces” (Tarr 2016). Less than two years later, Graham and McCain visited the frontline in Ukraine, “to pay tribute to the Ukrainian soldiers who are standing up to Russian aggression” and to urge coercive economic measures against Russia (Interpreter 2016).

This JMGTU, led by the US 7th Army Command, set up in 2015, was at first based in Lavoriv, western Ukraine, but later moved to Grafenwoehr, Germany. Its stated roles were to “Mentor and Advise Armed Forces of Ukraine Trainers” and to “Enable Combat Training Center Capability and Capacity” (7ATC 2022).

NATO think tank The Atlantic Council backed heavy weapons sales to Ukraine to modernise its military (Hasik 2014). In 2014, even before the Minsk agreements, NATO members had begun sending weapons to Ukraine, according to Kiev (BBC 2014b). In 2015, when US President Obama was claiming to send only non-lethal aid to Ukraine, even his defence secretary and other military leaders openly supported the idea of arms sales (Herb 2015). By 2017 and 2019, the Trump administration was selling Kiev heavy weapons, including anti-tank missiles (Martinez, Finnegan and McLaughlin 2019). So, well before 2022, the US military was directly training and arming Kiev’s military forces, not only to further the Donbass war but also to fight Russia.

Former UK military adviser Jamie Read, who said he had “fought in this war for more than three years”, spoke of ‘Operation Hammer and Sickle,’ where NATO-backed Ukraine forces aimed to “retake the Donbass” region (Read 2019). From inside the autonomous zone, officials regarded a major attack from Ukraine as a very real threat, adding that they hoped “that the threat of Russian intervention in the event of an attack on Donbass by Ukraine will prevent Kiev from going through with this bloody plan” (Donbass Insider 2020).

3. The question of self defence

As it happened, with large military mobilisations on both sides of the border, Russia launched a pre-emptive strike through its ‘Special Military Operation’ of 24 February 2022. Russian President Putin wrote an open letter to the United Nations (Putin 2022; Schmitt 2022), stressing the threat to Russia from NATO expansion, plus the threat to the Russian people of SE Ukraine, saying that one “cannot look without compassion at what is happening there. It became impossible to tolerate it. We had to stop that atrocity, that genocide of millions of people who lived there and who pinned their hopes on Russia, on all of us. In these circumstances, we have to take bold and immediate action. The people’s republics of Donbass have asked Russia for help” (Putin 2022). It was an argument for self-defence and humanitarian intervention. Western media characterised the speech as a ‘declaration of war on Ukraine’.

The Russian President saw an ongoing threat. “They will undoubtedly try to bring war to Crimea just as they have done in Donbass, to kill innocent people just as members of the punitive units of Ukrainian nationalist and Hitler’s accomplices did during the great patriotic war. They have openly laid claim to several other Russian regions. They did not leave us any other option for defending Russia and our people, other than the one we are forced to use today” (Putin 2022).

That brings us to the question of self-defence. Was the SMO, breaching the UN-recognised sovereign borders of Ukraine, carried out in self-defence? To put it another way, if the constant expansion of NATO and the war on Russian people of the Donbass represented a provocation, was there also an imminent threat to Russia from Ukraine?

Article 51 of the UN Charter says nothing “shall impair the inherent right of individual or collective self-defence if an armed attack occurs against a Member of the United Nations, until the Security Council has taken measures necessary to maintain international peace and security. Measures taken by Members in the exercise of this right of self-defence shall be immediately reported to the Security Council”. This Article was cited by the US-UK, in very different circumstances, for their 2003 invasion of Iraq.

Russia made a claim of anticipatory or pre-emptive self-defence, such as was used by the US and the UK for their invasion of Iraq. The operative phrase used to pre-emptively invade Iraq was that there was an “imminent threat” from weapons of mass destruction (Reynolds 2003; Rendall 2004), including from nuclear weapons.

At the same time as the SMO, Putin recognized the independence of two breakaway regions of eastern Ukraine, signing a decree recognizing the self-proclaimed ‘Donetsk People’s Republic’ (DPR) and the ‘Luhansk People’s Republic’ (LPR) as independent, prior to their accession to the Russian Federation (DW 2022). Russian troops were thus sent into the territories for “the function of peacekeeping”.

Of course, US- and NATO-aligned analysts objected. Some had argued that the ‘pre-emptive strike’ doctrine had been thoroughly discredited by the spurious rationales for the 2003 Iraq Invasion (Daalder and Lindsay 2004). Nevertheless, citing Washington’s 2002 ‘National Security Strategy’, British Professor of Public International Law Michael Schmitt (2023) felt “obliged” to take anticipatory self-defence seriously, but claimed such doctrine could not apply to the Russian intervention because (a) there was “no indication that NATO, or even Ukraine, had decided to mount an attack to retake Crimea” or Russia, and did not have “the forces in place to do so effectively”; and (b) the claim for Article 51 was “limited to states” and therefore did not apply to the Donbass region.

The former claim was wrong in fact, and the latter is an artificial distinction; indeed Schmitt recognises that intervention in cases of decolonization (i.e. for peoples and not states) has been legally recognised (Crawford 2007). Schmitt (2023) finally argues that the Russian intervention was also illegal because it does not meet the self-defence criteria of necessity and proportionality (e.g. as there were Russian attacks on Kiev). The question of proportionality is a distinct matter, which should be considered in the actual character of the SMO and its escalation, especially after greater NATO participation in the war.

The eight years of war waged by Kiev against the mostly Russian peoples of the Donbass was seen by Moscow as a real and present danger from a neighbour converted into the agent of an outside power. A key stated aim of the SMO, to defend the Russian people of the Donbass, cannot be lightly dismissed, even while the Russian state itself was said to be under attack from an expansion of NATO and the associated build-up of foreign backed forces near the borders of the Donbas.

By about April 2022 Russia controlled most of the Donbass region, plus a land bridge to Crimea (ISW 2022). Much of the war after that time – other than Russian attempts to secure remaining parts of western Donetsk, attacks on Ukrainian military centres and arms depots – had settled into a war of positions. By mid-2023, Kiev’s supposed ‘counter-offensive’ was attacking (with little success) a multi-layered defensive line created to protect the peoples of the Donbass.

The NATO states supporting Kiev did not want a settlement if that might be to Moscow’s advantage, so they sabotaged the peace talks. In 2023, Russian President Putin revealed that both sides had signed a document in Istanbul in which Ukraine would agree to place “permanent neutrality” in its Constitution, plus provisions limiting the size of Ukraine’s standing army during peacetime. Yet, as Ukrainian media Ukrayinska Pravda reported, former British Prime Minister Boris Johnson used a visit to Kiev to pressure Ukraine President Zelensky to cut off peace talks with Russia, even after the two sides appeared to have come to some agreement to end the war (Johnson 2022). It is clear that Johnson was acting on behalf of Washington, which has consistently maintained that Ukraine should fight to the end, or, as some have put it, “to the last Ukrainian” (Bandow 2022). This was seen as ideal by many in Washington, having a subordinate fight their wars for them; as senior Republican Senator Lindsey Graham said, “I like the structural path we are on, as long as we help Ukraine with the weapons they need and the economic support, they will fight to the last person” (Graham 2022).

President Zelensky later maintained that “negotiations can commence only after Moscow surrenders Crimea”, which voted to join Russia in 2014. He also dropped any idea of possible neutrality, and has formally applied to join NATO (Intel-drop 2023). NATO Secretary-General Stoltenberg said Ukraine should join NATO but only after the war (Ward and Bayer 2023). Given what Stoltenberg has said about the imperative of defeating Russia (Telesur 2022), that means after a supposed defeat of Russia.

Russia saw the war from NATO, via Ukraine, as an “existential threat,” which might even force Russian resort to nuclear weapons (Stoner 2022). Indeed, there have been many US and NATO arguments on the wish to not just “defeat” Russia but to “dismantle” it as a nation (Butler 2022). Evidence confirming those Russian fears kept emerging during the SMO. Discussions on the NATO side, assuming a necessary military victory against Russia, also argued the desirability of breaking up the Russian Federation (Tetrais 2023; Motyl 2023). This validated the Russian sense of deep threat and lent further weight to its claims of acting in self-defence.

That this self-defence was not widely recognised was probably due to several factors: deep adherence to the principle of inviolable UN-recognised sovereign borders, especially after the many US invasions; cynicism about big power claims of self-defence (and pre-emptive self-defence) after the fraudulent claims behind the US-UK invasion of Iraq; a very powerful propaganda campaign by the Anglo-Americans, asserting repeatedly that the invasion was “unprovoked”; and a reluctance to unnecessarily contradict the US-led bloc, for fear of retribution. Given the current domination of international agencies by the Anglo-Americans, it seems unlikely that any genuinely independent tribunal will ever be constituted to assess Russia’s self-defence claim. It will remain a historical consideration.

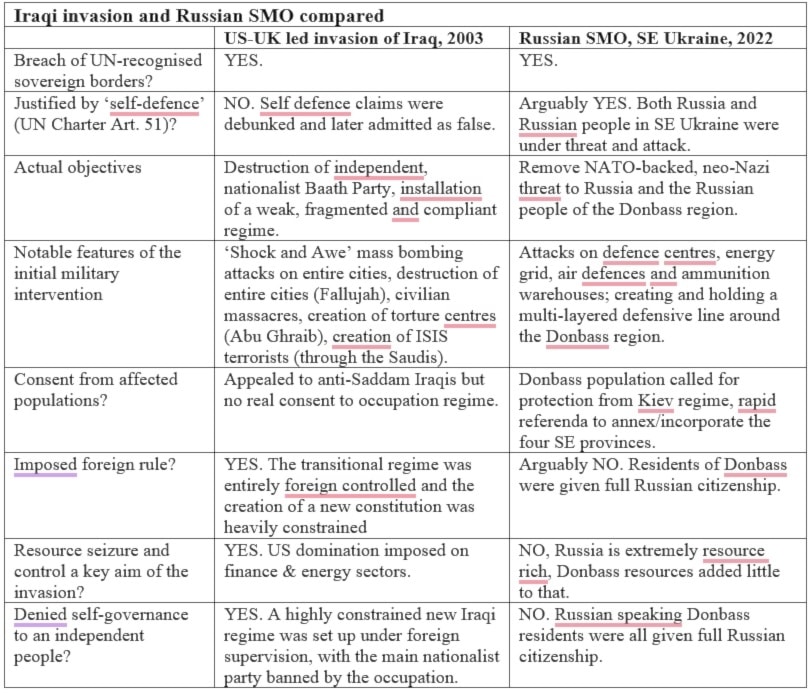

4. An imperial intervention, as in Iraq?

A related but distinct and wider question is, was the SMO an imperial intervention? Imperial invasions typically involve attempts to (1) impose foreign rule on an independent people, (2) appropriate resources without the consent of the indigenous or intervened population, and (3) deny the indigenous or intervened people a full say in their own governance.

All three criteria were met in the US-led 2003 invasion and occupation of Iraq. While many Iraqi people did not like President Saddam Hussein, they also did not invite the brutal ‘shock and awe’ bombing, indiscriminate slaughter and occupation regime. For fourteen months after the invasion, Iraq was subject to direct foreign governance through a Washington-appointed Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA), and then to a heavily compromised political process created by that same CPA (Dobbins et al 2009; Bremer 2023). The CPA disbanded the Iraqi army and banned the Baath Party (pan-Arab and socialist, but also the country’s main unified nationalist party) and its leading members, while emphasising constitutional division of the nation along sectarian lines, including through a federal system (Taras 2006; Dobbins et al 2009; Jawad 2013). Under these compromised structures US energy, construction, finance and military interests were embedded in the Iraqi system (Juhasz 2013; Mousa 2023; Beelman et al 2012).

Those compromises weakened the nation so much that the new state was almost destroyed by a second wave of ISIS warfare (Anderson 2019: Chapter 13). That terrorism was only really destroyed in Iraq by the nation’s own Popular Mobilisation Forces (PMF), with assistance from Iran’s Commander Soleimani (Chaudhury 2020; Younes 2020).

The US occupation falsely claimed credit for fighting ISIS. Despite its professed aims, the US military occupation (invited back into the country in 2014 by a weakened and US-dependent Iraqi administration) actually hindered the fight against ISIS (Cradle 2023). After all, as US Vice-President Joe Biden and then head of the US Army General Martin Dempsey admitted in 2014, Washington’s close allies armed and financed ISIS, and other terror groups, with the common aim of overthrowing the Syrian Government (CCHS 2021).

In Iraq the destabilisation was to prevent the re-emergence of a strong, independent state with close relations to Iran (Hersh 2007; Anderson 2019: 296-305). These US admissions stopped short of admitting direct US involvement with ISIS. Yet the January 2020 murder of Soleimani and PMF commander Abu Mahdi al Muhandis by the US military was called “divine intervention” by ISIS (Bowen 2020).

The Russian SMO in SE Ukraine had quite different features. It was said to be aimed at dismantling the Kiev-backed ultra-nationalist (Banderist and neo-Nazi) domination of the Russian speaking people of that region, and to avert a direct threat to Russia. Protection had been requested for some time by the self-proclaimed republics of Luhansk and Donetsk.

After the SMO, the Russian people of the Donbass region were not subject to foreign rule, but were rather invited to join the Russian federation as full citizens. The 2014 vote for Crimea to join Russia had been overwhelming and convincing; and that vote was soon confirmed by Western polls (BBC 2014a). The 2023 votes in the Donbass provinces were held in poor, war-torn conditions, but nevertheless reflected an indicative wish of many for Russian protection.

Groups in the Donbass had asked to join Russia as early as May 2014 (Walker and Grytsenko 2014). This “annexation”, as the Western powers called it, was in any case not a matter of imposing foreign rule, but rather the incorporation of Russian speaking people into a broader Russian body politic, where they would have full citizenship rights. Indeed, most of the older generations had lived under a Russian Centred Soviet system; most had also voted in 1991 against the dissolution of the Soviet Union, though they were persuaded later that same year to vote for an independent Ukraine, on the basis that it would be joined as an equal partner with its Russian neighbour and that the new Ukraine would open “wide opportunities for the development of languages and cultures of all nations” (Lavrenin 2022). The Kiev regime that emerged after the 2014 coup negated that multicultural promise.

Much was made, initially, about the distinction between an invasion and a Special Military Operation, but such terms do not define matters. Can there be non-imperial invasions? Yes indeed. The best recent examples have been the Tanzanian invasion of Uganda and the Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia (Chanda 2018), both in 1979. The Khmer Rouge-ruled Cambodian state was not only massacring Cambodian people, but also targeting and killing many ethnic Vietnamese (IRIN 2015). In short, Cambodia had become a failed state in the sense of one whose violence spilled across the borders, posing a serious threat to its neighbours. The Tanzanian invasion of Uganda followed Ugandan incursions and aggression against Tanzania (Avirgan and Honey 1982). In the cases of Vietnam, Tanzania and Russia, the invading party, a neighbour, was motivated by both direct aggression and the threat of cross border violence in such a way that put the neighbour and linked ethnic populations at serious risk.

The Anglo-American aims in Iraq were very different to those of the Russian SMO. Both claimed to act in the name of local people, but only the former imposed foreign rule. The ‘Shock and Awe’ approach in Iraq, and the devastation of the cities of Baghdad and Fallujah, were acts aimed at achieving “rapid dominance” through “massive and therefore indiscriminate bombing” (Ullman and Wade 1996). Both invasions breached UN-recognised sovereign boundaries, but the Russian claim of self-defence had substance, while that of the Anglo-Americans in Iraq did not.

Further, the culturally Russian residents of neighbouring SE Ukraine had called for intervention, and were very rapidly offered full citizenship. No such process existed in Iraq, where hatred of the foreign intervention and occupation grew over time. At the time of writing this article (early 2024), the US occupation of Iraq is still maintained against the very clearly expressed will of the Iraqi people and their institutions (Mitchell 2024).

It is unlikely that the Russian SMO in Ukraine will ever be judged by an independent tribunal, for reasons of power politics. That will remain a matter for historians. However the charge that the Russian intervention was an imperial operation fails because: (1) it did not aim to impose foreign rule, being rather a pre-emptive response to NATO expansion, plus a response to calls for protection from the mostly Russian people of SE Ukraine, suffering siege and aggression from the Kiev regime; (2) while there are significant natural resources in the Donbass region, it is plain that seizure of resources was not the key motivation of Russia, a country with massive natural resources; and (3) far from denying the intervened peoples a full say in their own governance, the Russian Federation moved to make them full citizens. There might be criticism of the mode and tactics of this SMO, but its rationale was quite clear. In any event, Russia clearly decided to redraw the post-USSR 1991 boundaries, and no one was able to stop her. The SMO was in many respects resolution of a war against Russia begun by the US through the 2014 Kiev coup.

In a second article, I will turn to the global impact question: how did the Russian SMO in Ukraine catalyse a turnaround in global alignments?

Link to the second article;

https://english.almayadeen.net/articles/analysis/the-russian-smo–1—was-it-an-imperial-intervention

Sources:

7ATC (2022) ‘Joint Multinational Training Group-Ukraine’, US Army, online:

https://www.7atc.army.mil/JMTGU/

Albanese, Chaira (2022) ‘Pope Repeats View NATO Positioning Was Factor in Russia War Move’, Bloomberg UK, 14 June, online:

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-06-14/pope-repeats-view-nato-positioning-was-factor-in-russia-war-move?leadSource=uverify%20wall

Allen, Duncan (2020) ‘The Minsk Conundrum: Western Policy and Russia’s War in Eastern Ukraine’, Chatham House, 22 May, online:

https://www.chathamhouse.org/2020/05/minsk-conundrum-western-policy-and-russias-war-eastern-ukraine-0/minsk-2-agreement

Anderson, Tim (2019) Axis of Resistance: towards an independent Middle East, Clarity Press, Atlanta

AP (2017) ‘US officials say lethal weapons headed to Ukraine’, 23 December, online:

https://www.cnbc.com/2017/12/23/us-officials-say-lethal-weapons-headed-to-ukraine.html

Avirgan, Tony and Martha Honey (1982) The Overthrowing of Idi Amin: An Analysis of the War, Zed Press and Westport, Connecticut

Azərbaycan24 (2022) ‘How the 2014 Odessa massacre became a turning point for Ukraine’, 2 May online:

https://www.azerbaycan24.com/en/how-the-2014-odessa-massacre-became-a-turning-point-for-ukraine/

Bandow, Doug (2022) ‘Washington Will Fight Russia to the Last Ukrainian’, Cato Institute, 14 April, online:

https://www.cato.org/commentary/washington-will-fight-russia-last-ukrainian

BBC (2014a) ‘Crimea exit poll: More than 90% back Russia union’, 16 March, online:

https://www.bbc.com/news/av/world-europe-26604221

BBC (2014b) ‘Nato members ‘start arms deliveries to Ukraine’’, 14 September, online:

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-29198497

Beelman, Maud; Kevin Baron, Neil Gordon, Laura Peterson, Aron Pilhofer, Daniel Politi, Andre Verloy, Bob Williams and Brooke Williams (2012) ‘U.S. contractors reap the windfalls of post-war reconstruction’, ICIJ, 7 May, online:

https://www.icij.org/investigations/windfalls-war/us-contractors-reap-windfalls-post-war-reconstruction-0/

Bowen, Jeremy (2020) ‘Qasem Soleimani: Why his killing is good news for IS jihadists’, BBC, 11 January, online:

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-51021861

Bremer, Paul (2023) ‘What went right in Iraq’, The Interpreter, Lowy Institute, Sydney, 16 March, online:

https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/what-went-right-iraq

Butler, Phil (2022) ‘The Plan Emerges: America’s Leadership Will “Dismantle Russia” for Good’, New Eastern Outlook, 29 June, online:

https://journal-neo.org/2022/06/29/the-plan-emerges-america-s-leadership-will-dismantle-russia-for-good/

CCHS (2021) ‘Syria by Admissions’, YouTube, 7 November, online:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9uBN522X-FA

Chanda, Nayan (2018) ‘Vietnam’s Invasion of Cambodia, Revisited’, The Diplomat, 1 December, online:

https://thediplomat.com/2018/12/vietnams-invasion-of-cambodia-revisited/

Chaudhury, Dipanjan Roy (2020) ‘Soleimani, face of fight against ISIS, Taliban’, The Economic Times, 4 January, online:

https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/soleimani-face-of-fight-against-isis-taliban/articleshow/73093126.cms?from=mdr

CNN (2008) ‘Bush: Missile shield no threat to Russia’, 1 April, online:

https://edition.cnn.com/2008/POLITICS/04/01/bush.nato/index.html

Cradle, The (2023) ‘Exclusive interview with Hezbollah commander in Iraq: ‘The Americans did not fight ISIS’’, 4 January online:

https://thecradle.co/articles-id/1728

Crawford, James (2007) The Creation of States in International Law, Oxford University Press, Oxford

Daalder, Ivo H. and James Lindsay (2004) ‘The Preemptive-War Doctrine has Met an Early Death in Iraq’, Brookings, 30 May, online:

https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-preemptive-war-doctrine-has-met-an-early-death-in-iraq/

Dobbins, James; Seth G. Jones, Benjamin Runkle and Siddarth Mohandas (2009) Occupying Iraq: a history of the Coalition Provisional Authority, National Security Research Division, Rand Corporation, online:

https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/monographs/2009/RAND_MG847.sum.pdf

Donbass Insider (2020) ‘IS THE DONBASS UNDER THREAT OF A NEW ATTACK FROM UKRAINE?’, 30 November, online:

https://www.donbass-insider.com/2020/11/30/is-the-donbass-under-threat-of-a-new-attack-from-ukraine/

DW (2022) ‘Russia recognizes independence of Ukraine separatist regions’, Deutsche Welle, 21 February, online:

https://www.dw.com/en/russia-recognizes-independence-of-ukraine-separatist-regions/a-60861963

FT (2021) ‘Russia demands NATO retract pledge to admit Ukraine and Georgia’, online:

https://www.ft.com/content/d86f8961-15c1-4f73-8cee-8251ab139204

Galen Carpenter, Ted (2022) ‘Many predicted NATO expansion would lead to war. Those warnings were ignored’, The Guardian, 28 February, online:

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2022/feb/28/nato-expansion-war-russia-ukraine

Glöckner, Olaf (2021) ‘The Collaboration of Ukrainian Nationalists with Nazi Germany’, in Complicated Complicity, online:

https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110671186-005

Graham, Lindsay (2022) ‘Senator Graham: With U.S. weapons and money, Ukraine will fight Russia to the last Ukrainian’, YouTube, 14 August, online:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Feg2xwUrQHM

Haas, Richard (1997) ‘Enlarging NATO: A Questionable Idea Whose Time Has Come’, Brookings, 1 March, online:

https://www.brookings.edu/articles/enlarging-nato-a-questionable-idea-whose-time-has-come/

Hasik, James (2014) ‘To Bolster Ukraine, Help Modernize its Arms Industry’, Atlantic Council, 10 March, online:

https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/to-bolster-ukraine-help-modernize-its-arms-industry/

Herb, Jeremy (2015) ‘Obama pressed on many fronts to arm Ukraine’, Politico, 11 March, online:

https://www.politico.com/story/2015/03/obama-pressed-on-many-fronts-to-arm-ukraine-115999

Hersh, Seymour M. (2007) ‘The Redirection’, The New Yorker, 25 February, online:

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2007/03/05/the-redirection

Intel-drop (2023) ‘Putin reveals details of draft treaty on Ukraine’s neutrality’, 17 June, online:

https://www.theinteldrop.org/2023/06/17/putin-reveals-details-of-draft-treaty-on-ukraines-neutrality/

Interpreter, The (2016) ‘US Senators McCain, Graham and Klobuchar Visit Front Lines In Ukraine; Trump Praises Putin’, 31 December, online:

https://www.interpretermag.com/day-1048/

IRIN (2015) ‘Did the Khmer Rouge commit genocide?’, RefWorld, online:

https://webarchive.archive.unhcr.org/20230520164811/https://www.refworld.org/docid/55f6a1d64.html

ISW (2022) ‘Ukraine Conflict Updates’, 15 August, online:

https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/ukraine-conflict-updates

ISW (2023) ‘Russian Offensive Campaign: assessment, 25 July 2023’, Institute for the Study of War, online:

https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-july-25-2023

Jawad, Saad (2013) The Iraqi constitution: structural flaws and political implications. LSE Middle East Centre Paper Series, 01. LSE Middle East Centre, London, UK.

Johnson, Jake (2022) ‘Boris Johnson Pressured Zelenskyy to Ditch Peace Talks With Russia: Ukrainian Paper’, Common Dreams, 6 May, online:

https://www.commondreams.org/news/2022/05/06/boris-johnson-pressured-zelenskyy-ditch-peace-talks-russia-ukrainian-paper

Juhasz, Antonia (2013) ‘Why the war in Iraq was fought for Big Oil’, CNN, 15 April, online:

https://edition.cnn.com/2013/03/19/opinion/iraq-war-oil-juhasz/index.html

Kramer, Mark (2014) ‘Why Did Russia Give Away Crimea Sixty Years Ago?’ Wilson Centre, CWIHP e-Dossier No. 47, online:

https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/why-did-russia-give-away-crimea-sixty-years-ago

Lavrenin, Petr (2023) ‘The ghost of Lenin: Why didn’t Russia and Ukraine sort out their border issues when the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991?’, RT, 9 January, online:

https://www.rt.com/russia/569302-russia-could-have-prevented-conflict/

Lopatonok, Igor and Oliver Stone (2016) Ukraine on Fire, IMDb, online:

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt5724358/

Martinez, Luis ; Conor Finnegan, and Elizabeth McLaughlin (2019) ‘Trump admin approves new sale of anti-tank weapons to Ukraine’, ABC News, online:

https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/trump-admin-approves-sale-anti-tank-weapons-ukraine/story?id=65989898

McCarthy, Bill (2022) ‘Fact-checking claims that NATO, US broke agreement against alliance expanding eastward’, Politifact, 28 February, online:

https://www.politifact.com/factchecks/2022/feb/28/candace-owens/fact-checking-claims-nato-us-broke-agreement-again/

MFA (2022) ’25 Questions about Crimea’, Russian Federation Ministry of Foreign Affairs,

https://mid.ru/upload/medialibrary/7f9/25QCrimeaEN.pdf

Mitchell, Ellen (2024) ‘Iraq wants US military out’, The Hill, 5 January, online:

https://thehill.com/newsletters/defense-national-security/4392394-iraq-wants-us-military-out/

Motyl, Alexander (2023) The Ukraine War might really break up the Russian Federation, The Hill, 13 August, online:

https://thehill.com/opinion/international/4149633-what-if-russia-literally-splits-apart/

Mousa, Zaher (2023) ‘The US holds Iraq hostage with the dollar’, The Cradle, 22 January, online:

https://thecradle.co/articles-id/1570

NATO (2023) ‘Enlargement and Article 10’, 12 April, online:

https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_49212.htm

NATOWatch (2018) ‘How Gorbachev was misled over assurances against NATO expansion’, 2 January, online:

https://natowatch.org/newsbriefs/2018/how-gorbachev-was-misled-over-assurances-against-nato-expansion

Novaya Gazeta Europe (2023) ‘”Should have started earlier”: Putin in response to Merkel’s comments that Minsk Agreements were an attempt to give Ukraine time’, 10 December, online:

https://novayagazeta.eu/articles/2022/12/09/should-have-started-earlier-putin-in-response-to-merkels-comments-that-minsk-agreements-were-an-attempt-to-give-ukraine-time-en-news

NSA (2017) ‘NATO Expansion: What Gorbachev Heard’, online:

https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/briefing-book/russia-programs/2017-12-12/nato-expansion-what-gorbachev-heard-western-leaders-early

Nuland, Victoria (2013) Remarks at the U.S.-Ukraine Foundation Conference’, US Department of State, 13 December, online:

https://2009-2017.state.gov/p/eur/rls/rm/2013/dec/218804.htm

OHCHR (2022) ‘Conflict-related Civilian Casualties in Ukraine, Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, 27 January, online:

https://ukraine.un.org/en/168060-conflict-related-civilian-casualties-ukraine

Peacemaker (2015) Protocol on the results of consultations of the Trilateral Contact Group (Minsk Agreement)’, United Nations, 5 September, online:

https://peacemaker.un.org/UA-ceasefire-2014

Pifer, Steven (2014) ‘Did NATO Promise Not to Enlarge? Gorbachev Says “No”’, Brookings, 6 November, online:

https://www.brookings.edu/articles/did-nato-promise-not-to-enlarge-gorbachev-says-no/

TheAltWorld

TheAltWorld

Guy St Hilaire

Thank you Tim .Well documented.