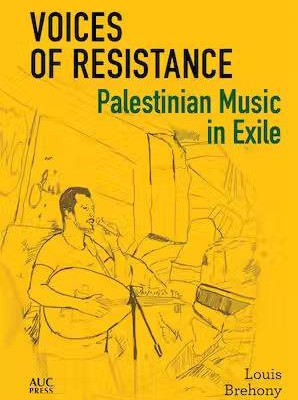

Palestinian Music in Exile: Voices of Resistance

- Book Author(s):Louis Brehony

- Published Date:October 2023

- Publisher:AUC Pres

- ISBN-13:9781649033048

“There is no location of Palestinian exile that has not produced its own musicians or musical experiences.” Louis Brehony’s book Palestinian Music In Exile: Voices of Resistance vividly portrays the Palestinian anti-colonial resistance through music by bringing forth Palestinian voices mainly through the refugee experience, which is also a collective experience, given the centrality of the 1948 Nakba and the various forms of displacement Palestinians have faced. As Brehony writes in the introduction: “Palestine is itself a site of exile.”

Exile and movement cannot be separated from one another. Brehony notes recent instances of Palestinian resistance where music became one of the central forms of sumud, notably Israel’s efforts at forcibly displacing the residents of Sheikh Jarrah in 2021. As Palestinian musicians echoed the call to liberation through music, the performers and cultural institutions were not spared, and Israel’s repeated efforts to obliterate Palestine also resulted in a strengthening of Palestinian memory as music became a collective performance.

Brehony’s ethnographic study was conducted over a span of ten years in countries closest to Palestine and with a strong Palestinian refugee presence. What stands out immediately in the book is the centrality of refugees to the Palestinian anti-colonial struggle. Refugee narratives have contributed to Palestine’s oral history, and the musical narratives imparted in this book by the musicians interviewed for the research shed light on the experiences of exile and how renewal is not dissociated from Palestinians’ historical memory.

The book delves into the subject from a Marxist framework and brings together the concepts espoused by Ghassan Kanafani, Leila Khaled and Naji Al-Ali – themselves having been exiled from Palestine – alongside the cultural theories of Edward Said and Frantz Fanon, among others.

Brehony argues: “Under colonial relations and displacement, the reclaiming of public space has gone hand in hand with aesthetic revolution, broadening and traditionalising the sounds of Palestine, responding to historical crises and recollectivising narratives and forms of displacement.” One major recurring theme is the 1948 Nakba, which gives rise to the various experiences of exile as well as the difficulties in researching Palestinian music. In the absence of documented historical research, Palestinian oral history becomes imperative, and it is also intertwined with Palestinian music itself, in terms of the musicians’ own background of displacement from Palestine, the countries where they lived in exile, the imagining and right of return, the song lyrics and the instruments used.

The association of Palestinian song with weddings is prominently discussed in the book. Weddings are described as: “The most powerful social space in which conceptions of nation are defined, redefined and transmitted.” Oral transmission of Palestinian recollections is a prevailing theme in Palestinian song, and Brehony states: “Weddings themselves are often sites of repression and resistance, both in Palestine and in exile.”

The Palestinian musicians interviewed for this book provide contrasting and differing experiences of music and exile in terms of social status, the countries in which they resided following their displacement from Palestine, their economic situation and the prevailing ramifications of colonial and imperialist violence. Palestinian revolutionary song also went through different trajectories as a result of the musician’s interaction with, and influence of, the host country, as well as the singer’s individual understanding, experience and concept of Palestine. Music is a challenge to colonial displacement, and the refugees’ displacement experiences and narratives constitute a collective common ground, which makes Palestine a constant despite the Zionist colonial expansion. For example, Brehony writes of the Palestinian refugee experience in Jordan, which, despite its fame as the heart of the diaspora, suppresses commemorations of the Nakba. The book also notes that Palestinian refugees in Lebanon have faced the worst exile conditions while Palestinian refugees in Syria, notably those living in the Yarmouk refugee camp, suffered another displacement as a result of the so-called Arab Spring. The Palestinian refugees’ interaction with the host countries also led to expression as regards: “State policies, ruling ideologies on culture, war, and resistance, and the impact of region and international events.”

Through the musicians’ narratives, the intricacies of history, which are generally obscured, are brought to light as Palestinian singers narrate their own experiences of exile, their concept of performance as a career or contributing to their immediate surroundings without aspirations of public performance and the overcoming of elitist connotations with music. The oral history narrated by the musicians and the lyrics accompanying Brehony’s detailed and meticulous study testify to the Palestinian return being the central theme in music and stories, allowing the author to draw similarities between Palestinian revolutionary music and Palestinian literature. The historical context, Brehony argues, is essential to understanding the lyrical homeland depictions, which would also require a broad understanding of the Palestinian resistance in its entirety and how it reflects in song, including the invitation to participate as part of a collective experience.

Brehony’s research also dives into the various facets of colonial control and anti-colonial resistance, drawing the reader into a discussion of Palestinian refugees who remained in Israel and their resistance despite Israel’s efforts to obliterate their identity and the attempts by externally funded music schools for Palestinians to exploit Palestinian musicians while contributing to the division of social classes through elite structures and enrolment. It also addresses the neocolonialism of Ramallah, described as “a false oasis under occupation”, and encapsulates what Palestinians are struggling against, also from within.

Besides providing an in-depth look at Palestinian revolutionary song, the attention and detail in terms of context make this book not just an incredible read but also provide a more tangible experience of reading about Palestine for non-Palestinians. Anyone reading this book would do well to keep it as a permanent source of reference.

https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20240210-palestinian-music-in-exile-voices-of-resistance/

TheAltWorld

TheAltWorld

0 thoughts on “Palestinian Music in Exile: Voices of Resistance”