British government continues to aid repression in human rights-abusing countries, new data shows

By Mark Curtis and Matt Kennard- The British government is continuing to approve the export of hi-tech surveillance equipment and software of the type that is being used by states abusing human rights to monitor and repress dissent, new government figures show. The government’s exports of ‘telecommunications interception equipment’ to repressive states are likely unlawful.

In the past 12 months, “telecommunications interception equipment”, or software and technology for such equipment, has been exported to 13 countries, including authoritarian regimes such as the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Saudi Arabia, Oman and Qatar.

Such technology enables security forces to monitor the private activities of groups or individuals, potentially enabling them to crack down on political opponents. Especially controversial are so-called IMSI-catchers, a sophisticated surveillance technology which can monitor phone conversations, text messages and private information stored on mobiles. IMSI-catchers are considered so sensitive that the British police have refused to confirm or deny whether it uses them.

Recently released British government figures make clear that many of the approved exports are destined to “law enforcement” agencies of foreign governments.

The new data lends further weight to those calling on the British government to cease such exports in light of evidence they help fuel repression overseas and are illegal because they violate the government’s own export control guidelines.

Licences for the United Arab Emirates

The most recent data shows that from January to March this year, the UAE was granted three licences for “communication and network surveillance” equipment and software, which the UK government notes are for “interception purpose”. The data also makes clear that this equipment is for “law enforcement agency end use”.

The UAE is one of the Gulf region’s most repressive states, where criticism of the government is “stifled by the prosecution and imprisonment of peaceful dissenters” and where space for civil society remains “nearly non-existent”, according toAmnesty International.

Last year, Ahmed Mansoor, the last human rights defender in the UAE publicly speaking out against human rights violations in the country, was sentenced to 10 years in prison for comments posted on social media. In a story that made headlines in 2016, Mansoor’s iPhone was hacked by the UAE government with software provided by an Israeli-based security company. Emirati authorities reportedly paid $1-million for the software, leading international media outlets to dub Mansoor “the million-dollar dissident”.

In 2016, the US investigative website, The Intercept, published evidence of UAE government involvement in surveillance of the country’s citizens to track, locate, and hack any person at any time. Programs were used to mount attacks on journalists and activists involving spyware sent through Twitter, spear-phishing emails and a malicious URL shortening service. These programmes had been taking place since 2012, a source told The Intercept.

These revelations followed a report in the New York Times showing the UAE had attempted to install spyware on the computers of 1,100 dissidents and journalists. The spyware was found to have been sent by a company owned by a member of the Abu Dhabi royal family.

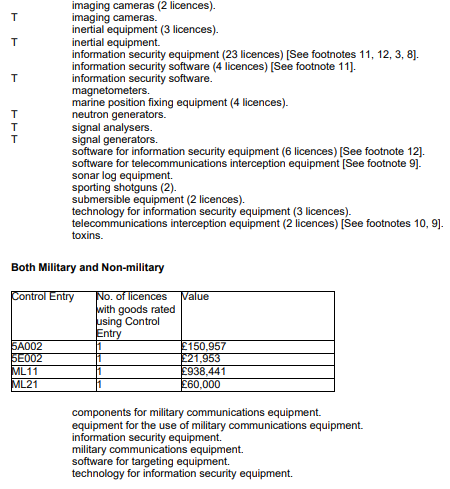

The UAE is a regular recipient of such surveillance equipment and technology from Britain. In 2017 and 2018, British exporters were given four licences for the export of telecommunications interception equipment, components or software to the UAE.

More exports to the Gulf

British government figures show that similar licences for telecommunications interception equipment were awarded for export to Saudi Arabia in 2018, also destined for use by its dictatorial regime.

Britain also approved licences for similar equipment to Oman in 2017 and 2018, some of which was for “marketing and promotional purposes”, but software for telecommunications interception equipment intended for use by the regime was also exported, the data shows.

Another dictatorial Gulf state, Qatar, was awarded several licences for such equipment during 2018, including for “government end use”.

Yet another repressive regime, Bahrain, was given approval to receive telecommunications interception equipment, alongside relevant software, from British companies in 2017 and 2018, although these are designated for “civilian/commercial end use”.

Other approvals to Bahrain include 15 licences for “information security equipment” and software. It is unclear what these goods are but some are for use by the government and thus raise long-held fears they will aid repression.

Bahrain has stepped up its repression of the political opposition since a significant uprising as part of the Arab Spring in 2011. Most human rights defenders and dissidents have been jailed, silencedor forced to move abroad in recent years, while public protests are officially banned in Manama, the capital.

Moreover, it has long been known that the Bahraini authorities target activists through surveillance technology. It is believed that Bahrain has been conducting communications surveillance on activists and opponents since at least the mid-2000s. In June 2019, the Bahraini authorities warned citizens and residents that even following anti-government social media accounts could result in legal action.

Surveillance of Bahraini activists by the regime has even occurred in the UK itself. In 2014, the NGO Privacy International brought a criminal complaintto the National Cyber Crime Unit of the UK’s National Crime Agency, calling for an investigation into the unlawful surveillance by Bahraini authorities of three Bahraini activists living in the UK.

The Bahraini authorities infected the activists’ computers with the intrusive malware FinFisher, supplied by British company Gamma. The three activists – who had been granted asylum in the UK – had suffered from years of harassment and imprisonment by the regime, and were subject to torture at the hands of the Bahraini government.

Unlawful exports?

The UK’s arms export guidelines state that the government will “not grant a licence if there is a clear risk that the items might be used for internal repression”. It defines the latter as including “torture and other cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment or punishment; summary or arbitrary executions; disappearances; arbitrary detentions; and other major violations of human rights”.

Reports by Amnesty International clearly document such abuses in the cases of Bahrain, UAE, Saudi Arabia and Oman. British approval of such exports is therefore prima facie illegal.

Since 2015, the UK has granted 283 export licences for the export of surveillance technology, components or software, with the UAE, Oman, Saudi Arabia and Qatar all among the top 10 recipients. One estimate is that these exports have been worth more than £75-million.

One major company in this field is the UK’s largest arms exporter, BAE Systems, which sells surveillance technology to up to 50 countries, many of which are not subject to UK licensing requirements since they are sometimes exported from companies in the BAE group outside the UK.

A BBC investigation in 2017 found that BAE Systems sells sophisticated surveillance technology across the Middle East to states including Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Qatar, Oman, Morocco and Algeria.

A BAE engineer was interviewed by Vice News this year and said, in relation to exports to the Gulf regimes, “Obviously we do work very closely with Cheltenham, who know everything we do.” Cheltenham, in southwest England, is the home of the UK government surveillance agency, GCHQ. BAE Systems Applied Intelligence, the cyber arm of the company, has offices in nearby Gloucester, where it says it “delivers information intelligence solutions to government and commercial customers”.

In July this year, it was revealed that the UK approved £1.9-million worth of telecommunications interception equipment for export to Hong Kong. This came just weeks before mass protests against the controversial proposed treaty with mainland China began in March.

The risk of such technology being used for repression is well-known to the government officials approving them.

In 2017, Computer Weekly obtained internal UK government correspondence showing how departments assess licence applications. It confirmed the lack of any suitable risk analysis for such applications. The documents showed that, in 2012, the UK approved a licence to export an IMSI-catcher to an agency in Macedonia. This technology was eventually used by the government for the illegal mass wiretapping of 20,000 activists, politicians, and journalists.

Refusing licences

The British government data includes some licences which have been rejected or revoked, confirming that officials are aware of the sensitive nature of these exports, and maybe the legal implications. In 2018, licences for telecommunications interception equipment were refused to Bangladesh, Vietnam, Serbia, and Nigeria.

Licences for Bangladesh were refused or revoked between July and December 2018. This was at a time when the Bangladeshi government was engaged in a fierce response to protests against ongoing corruption in the country, with protesters and journalists being beaten and detained by security forces. It was also a period when the Bangladeshi security forces reportedly went on a shopping spree to purchase surveillance technology.

But no such licences have recently been refused to Britain’s allies in the Gulf, whose regimes are undoubtedly worse in terms of their human rights records. Indeed, the government refuses very few licence applications at all. Only 3.2% – or nine out of 284 applications for internet surveillance and telecommunications interception equipment – were refused in the four years from 2015-18 due to the risk of internal repression.

Licence not required

Neither do all surveillance exports even require a licence from the government. While telecommunications interception equipment is subject to export controls if this is for mobile phones, such equipment for “lawful” interception of networks, rather than devices, is not. This would include technology for mass surveillance run by repressive regimes, similar to the NSA’s Prismprogram.

Another boom area for the industry is facial recognition technology, which if acquired by government agencies can enable them to identify individual protesters. This is also not included in the list of goods subject to UK export controls, and companies have told the authors that they freely export such technology with no such regulation.

Supporting Gulf regimes

Given key British interests in the Gulf – where Britain has recently established new military base facilities in Bahrain and Oman – the government almost certainly views the export of surveillance equipment as another facet of its long-term support for the regimes in these states.

Promoting “internal security” has long been a feature of British policy in the Gulf, meaning to help keep ruling families in power. In its latest annual report, the Ministry of Defence states that UK military training programmes, which are provided to nearly all the Middle East’s repressive regimes, “can offer very specific and immediate benefits to our international partners, for example… improving the capacity of partners to deal with internal security challenges”.

Britain has since 1964 had a training programme for the Saudi National Guard, the body that protects the ruling royal family, and also trains the Royal Guard in Oman, Kuwait and Qatar.

In 2011, Britain helped the Bahraini regime put down popular protests threatening ongoing Sunni sectarian rule over the country. London fears regime change in the region upsetting its substantial military, trade and investment interests.

Protecting the industry

Surveillance equipment used by government agencies is manufactured by hundreds of private corporations around the world. Most of these companies, however, are based in the major arms-exporting states with the biggest spy agencies.

The UK is at the heart of the industry, with over 100 companies providing equipment or services, the second-largest number in the world after the US. Many firms are based around GCHQ’s base in Cheltenham, which the government has worked to turn into a hub for cybersecurity firms. Northrop Grumman, BAE Systems Applied Intelligence and Raytheon are among the major military corporations which have operations in the area around Cheltenham, alongside a larger number of smaller firms.

But secrecy prevails on the recipients of the exported equipment.

This month, one of the UK’s most senior national security reporters, Ian Cobain, was banned from attending the world’s largest arms fair, DSEI, in London, which is organised in part by the UK government.

Similarly, in March this year Labour MP Lloyd Russell-Moyle was also banned from attending a “security trade” fair in the UK to which the government had invited numerous of the world’s most repressive regimes. Moyle, who sits on parliament’s all-party arms control committee, was denied entry to the fair precisely at the time he was investigating the UK’s surveillance industry.

Increasing, not ending exports

Earlier this month, the British government published a new Security Export Strategy, covering surveillance and cybersecurity equipment, among other areas. It highlighted that “the UK is a world-leader in the security sector” and the world’s fourth-largest exporter, adding that the government would “accelerate the continued year on year growth of security exports”.

Increasing British government backing for the spy tech industry flies in the face of rising international calls to ban exports of such technology.

In June this year the United Nations Special Rapporteur on freedom of opinion and expression, David Kaye, called for an immediate worldwide moratorium on the sale, transfer and use of surveillance technology until human rights-compliant regulatory frameworks are in place.

He noted, “Surveillance tools can interfere with human rights, from the right to privacy and freedom of expression to rights of association and assembly, religious belief, non-discrimination, and public participation. And yet they are not subject to any effective global or national control.”

Kaye’s call follows the European Parliament which in 2018 voted to tighten export controls restricting the supply of surveillance and encryption technology to regimes with poor human rights records. The new restrictions would apply to surveillance equipment including devices for intercepting mobile phones, hacking computers, circumventing passwords and identifying internet users.

Aside from UK and EU export controls, the world’s major accord governing international exports of arms and dual goods including surveillance technologies, known as the Wassenaar Arrangement, suffers from the problem of being voluntary rather than mandatory.

Calls to curb exports of surveillance technology are likely to be vigorously opposed by the British government, along with the private companies benefiting from the burgeoning infrastructure it has nurtured in this industry sector. But unless laws are tightened and enforced, the greatest price may continue to be paid by those challenging repressive systems in the Middle East and elsewhere.

https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2019-09-20-british-government-continues-to-aid-repression-in-human-rights-abusing-countries-new-data-shows/

TheAltWorld

TheAltWorld

0 thoughts on “British government continues to aid repression in human rights-abusing countries, new data shows”