Geopolitics of South Asia and Interests of Russia

If we are talking about geopolitics, we must apply an integrated an complex approach that combines power (primarily hard power – military strength and economic) and a certain view on the territory issues. The key concepts in geopolitics are Land Power, Sea Power and Manpower. The first two categories relate to geographical determinism and people are more likely to adjust and adapt to environmental conditions, trying to extract from this rational use – mountains, deserts, rivers and seas can serve both as natural boundaries and as a source of well-being. Man Power refers to the field of pure politics – the human will can determine how to develop the territory, whether to use military force, what to do for development and strengthening the national economy, as well as what ideological factors can serve – religions and other forms collective identity, such as nationalism.

In this article, we will look at geopolitical factors, including those numerous drivers that push the centripetal and centrifugal forces of the region. Also we will analyze the perception of South Asia from three positions. To do this, it will be necessary to understand the interests of not only the countries of the region, but also others global players. And Russia’s interests cannot be understood without Western opposition, especially in the context of current international relations.

At the same time, we must take into account global geopolitical turbulence and the tectonic shift from a unipolar to a multipolar world order.

Global positioning of the region

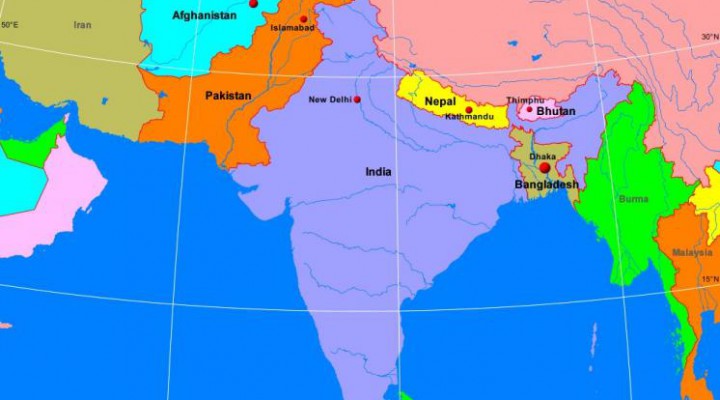

There are different definitions of South Asia. Some refer to this region as the territories that were previously controlled British empire.1 According to the most common version, South Asia includes eight States: Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka.

If we consider the region from a global position, South Asia is the Rimland zone – the coastal zone of Eurasia, characterized by active dynamics, which is confirmed by the historical facts of the presence of the centers of ancient civilizations, trade and migration routes, as well as the banality that more than 70% of the World’s population lives off the banks of rivers, seas and oceans.

The history of the last two centuries shows that this Rimland has become a place of intense pressure from Sea Powers -early Britain, then the United States. The logic of Land Power forced the Russian Empire, and then the Soviet Union to respond in a manner based on instruments of deterrence and then ideology.

If the US had once followed the doctrine of Henry Kissinger’s rollback and used the myth of the Communist threat, now Washington has a more difficult time justifying its presence in the region. In addition, Russia is separated from these countries by a buffer of the independent states of Central Asia. Although the political reality has changed, the geopolitical logic remains the same.

Russia-Heartland is interested in integration processes, while Sea Power, represented by the United States, is interested in controlling the coastal zone.

This is evident from a number of strategic documents. If you have previously under the administration of Barack Obama, the focus was in the South-East Asia and the creation of the Pacific pivot was announced, a new model of the Indo-Pacific region was emerged just now.2

Geopolitics of the region

It is obvious that according to its geopolitical characteristics and significance, there are three most important States, which are in the Heartland of South Asia. These are Afghanistan, Pakistan and India. The rest of the countries serve as a kind of buffer and objective reasons can not have a fundamental impact on the geopolitical processes in the region. The role and status of the other five States are limited, they fall into the sphere of influence of other actors, although they can act as significant subjects. So, for example, Sri Lanka has become an important element in China’s “Strings of Pearl” strategy.

If we use the terminology of Zbigniew Brzezinski, proposed in his work “The Great Chessboard”, on the regional scale Afghanistan, Pakistan and India are active geopolitical actors, while Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan, Maldives and Sri Lanka as geopolitical centers with varying degrees of importance. Afghanistan we attributed to the actors because of the strategic instability of this state and the influence it has had on the policy of Eurasia for the last 35 years. In some sense, it is negative geo-political actor.

In South Asia context itself, regionalism may be analyzed from different contexts i.e. positive and negative.3

It should also be borne in mind that with the exception of Sri Lanka and the Maldives, whose borders are natural due to their island situation, the remaining six states’ borders are the result of the intervention of the British Empire and the consequences of the colonial policy of London, which is still felt to varying degrees throughout South Asia.

This has created the effect of grey zones and hybrid borders, which are characterized by a high degree of political tension. A number of states have certain vulnerabilities in the form of hotbeds of instability, which can be classified as gray zones.

The disputed territory is Kashmir. In addition, India has a disputed territory with the People’s Republic of China. Killings of Bangladeshi citizens by Indian border guards on the Bangladesh-India border are facts not often reported in the international press, but are indicative of the characteristics of Indo-Bangladeshi relations. In India itself there is a threat from the Maoist Naxalites in the North-Eastern States. The Western States of India may be subject to manipulation from radical Islamists. However, the growth of Indian hindutva nationalism also provokes instability.

In general, most countries in South Asia are characterized by domestic political problems associated with threats of terrorism and separatism.

There is regional entity presented by interstate organization – The South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation or SAARC that was established on December 8, 1985.4 However, we see that many initiatives within this organization are still at the stage of organizational decisions. It is also important, that this platform can serve as a venue for a regional polylogue, including a discussion of various critical issues.

The theory of the three worlds

For an adequate understanding of the processes taking place in South Asia, it is necessary to take into account not only the political contradictions and tensions between the countries of the region, but also the view from the outside. Therefore, we will inevitably come to the need to consider South Asia from three positions. There is a well-known concept of the three worlds. The first world is represented by industrialized countries.

The second world are countries in the process of technological development. The third world is represented by countries that have yet to go the way of development. This theory represents the Western point of view and has a certain element of racism to it.

In our case the three worlds are three perceptions of South Asia – from South Asia itself, from Russia (as we consider Russia’s interests in region) and the United States, as this state still claims to be a global hegemon and openly declares persecution its objectives in Asia, some of which are clearly contrary to the development strategies of a number of States in the region.

Conflict of interest is clear in the frame of US strategy and interests, but it is covered by specific bilateral policies and the general diplomacy of the State Dept. The United States has traditionally been interested in maintaining the conflict potential between countries in order to face different sides and depending on the situation to take one side or another. Ex Secretary of Defence Ash Carter in the context of American strategy for Asia noted that “The heart of that policy is a mesh of political, diplomatic, economic, and military relationships with many nations that has sustained security and underwritten an extraordinary leap in economic development.”5

His idea is to establish kind of network for Asia. “Important to see these relationships as an informal network — not an alliance, not a treaty, not a bloc” – wrote Carter in his “Reflections on American Grand Strategy in Asia.” In his opinion “The network structure suits Asia.”6

It is significant that in this speculative network structure, he deliberately introduces an enemy element. At least China is represented as a kind of power that not only opposes American interests in the whole region, but also conducts activities, undermining the sovereignty of other States.

“Maritime and cyber activities are two forms of Chinese aggression that cause concern in the states of the Pacific network, which deepens China’s self-isolation. China’s actions in the South China Sea are a direct challenge to peace and stability in the Pacific”.7

It is important to note that Carter mentions China not only as a military-political actor, but also as an economic power.

“The China-proposed network would include such initiatives as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (IAAB) and One Belt, One Road (OBOR)—both of which would be detrimental to U.S. interests. The IAAB,a potential rival to the World Bank and International Monetary Fund, would not match the high standards of the WB and IMF in relation to governance, environmental, and other safeguards—and OBOR is likely to extend China’s political influence more than it extends actual property”.8

India, on the contrary, is described as a potential ally of the United States, and therefore as a kind of proxy power, able to be a conductor for Washington’s interests in the region.

“India is another example of how the strategic benefits of the principled, inclusive network can overcome hesitation. Once deeply skeptical of U.S. influence in South Asia, India became a more active participant in regional security during my two years as Secretary of Defense than at any time in its history”.9

It is possible that Carter’s position reflects the political instability throughout Asia, described by Robert Kaplan more than 20 years ago?

“The future map – in a sense, the ‘last map’ – will be a constantly changing representation of the cartographic chaos, in some areas favorable or even productive, and in some violent… This card will be all less and less applied by the rules that diplomats and other political elites have been ordering for centuries. Decisions will mainly come from within the cultures themselves, exposed to those decisions.”10

But this instability is a special feature – it is neither anarchic chaos, or geopolitical tabula rasa. Rather, these are new opportunities that are associated with global changes, but have their own characteristics of a deep nature. Russia’s view of South Asia will be discussed in the relevant section on strategies. Now we have to ask – does Asia look at itself with Asian eyes?

It is obvious that in South Asia to a greater or lesser extent in different countries there is a problem of colonization of consciousness, although all States are formally sovereign. These questions often become the subject of Subaltern Studies in European and American Universities.

And “the formation of different disciplines, including production of Western Orientalist scholarship on Asia was directly or indirectly related to the patterns of domination of Asia. The disciplinarisation and systematisation of human knowledge was a part of the project of modernity.“11 The attempt of South Asian States to build themselves under the model of Western institutions – hence, for example, the well-known aphorism that India is the largest democracy in the world, although it is not because of the actual caste system – and statements by the officials of Asian countries regarding common interests and values thus look pretty paradoxical.

Interests and values

Now we need to decide on a taxonomy related to interests. The point is that the concept of interests in politics can differ depending on which school of international relations is taken as a pattern. In realism, the state it is perceived as a rational subject that acts like a human being and is guided by common sense. However, since Thucydides, we know that human behavior itself is irrational, especially when decisions are made under the influence of anger, greed and ambition. Machiavelli, who is considered one of the harbingers of realism introduced a division of ethics and politics, justifying any kind of action if it leads to the desired goal.

At the liberal school of international relations “achieving peace” is spoken of as a kind of imperative. In practice, as we know, it turns into wars and interventions.

A kind of marker is the Democratic and Republican parties in the United States. The Democratic party tends to gravitate toward the liberal school, while the Republicans adhere more to realism. At the same time, both theories are Western in origin and they are considered to be standards for international relations at the global level.

In addition, the structures of States differ in substance. In the US, there is a model of iron triangles when lobby groups can actively influence international processes. An example is the decision to invade Iraq in 2003, when neoconservatives controlled the military-political apparatus of the presidential administration. Lobby groups of influence may include both ideological structures and commercial ones, for example, transnational corporations. And in Pakistan and Russia are other socio-political models, which are rooted in centuries-old traditions. So even if we try to withdraw some of the formula of net interests (for example, quotas for the supply of some goods or services, the size of duties, admission to the market a certain number of companies) – it will be almost impossible to do.

Another reason is the different sizes of state economies and the availability of priority sectors in the industry. Russia is among the leaders of the countries exporting gas and oil. Pakistan has its own economic priorities, India has its own as well.

However, in addition to interests, there are always values. Interests can be negotiated, values represent a static phenomenon that are not negotiable. Of course, values can be eroded or deeply influenced by exogenous impact. And with modern technologies of social engineering in certain conditions, the change of value orientations can happen very quickly, especially if charismatic public opinion leaders from the local environment are involved. On the example of Ukraine we can see how with the help of external influence values were restructured by socially-political processes and changed the identity of the Ukrainian people.

Values also include the phenomenon of nationalism, which differs from country to country and from region to region. South Asian nationalism, as Sayantan Dasgupta aptly puts it, is ‘monstrous,’ with much of the discourse surrounding it tending to further stoke the conflict between the notion of nationalism as empowerment and as an exercise of homogenization. Languages of power and struggle for belonging through language are most acute in South Asia.12 When fragmentation is possible to detect such details as, for example, the description of the Taliban as a “nationalist Islamist insurgency, who, for his own purposes, feeds and manipulates tribal imbalances and rivalries.”13

However, on the scale of the value system it is possible to consider whether the interests of one country can be interfaced with the interests of another country. It seems to me that representatives of the two States will be able to reach an agreement with each other faster if their countries have traditional family values. But if one country has a patriarchal system and another country has legalized same-sex marriage and political feminism is a fashion trend, it will be harder to do so.

Strategies of Russia in general and in relation to Asia in particular

It is important to understand that there is no clear definition of Russia’s actions in the international arena. On the one hand, there are a number of documents, related to national security and foreign policy. But they are more likely to wear desirable and recommendatory character. A number of provisions that are spelled out in these strategies, despite their important nature, have never been realised. For example, in the national security doctrine of 2008, it was said that Russia has the right to apply its armed forces abroad to protect its citizens. But the case of Ukraine has shown that this item has not found its applications, although there were numerous facts indicating the possibility of its implementation.

A number of existing strategies also have some aspects that are difficult to put into practice. In other words: the desire and reality are different. However, a number of excerpts from these documents are needed to show the general trends and some limitations in the strategic thinking of the persons who made up these doctrines.

We will cover only those items that relate to the region under consideration or reflect the attitude towards the international community.

In The Foreign Policy Concept of the Russian Federation (approved by President of the Russian Federation Vladimir Putin on November 30, 2016)14we see several points connecting with Asian issues.

79. Russia attaches importance to further strengthening the SCO’s role in regional and global affairs and expanding its membership, and stands for increasing the SCO’s political and economic potential, and implementing practical measures within its framework to consolidate mutual trust and partnership in Central Asia, as well as promoting cooperation with the SCO member States, observes and dialogue partners.

80. Russia seeks to reinforce a comprehensive long-term dialogue partnership with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and achieve a strategic partnership. Efforts in this area will be supported by expanded cooperation within such frameworks as the East Asia Summit, which provides a platform for strategic dialogue between country leaders on conceptual issues related to the development of the Asia-Pacific Region, the ASEAN Regional Forum and ASEAN Defence Ministers’ meeting with the dialogue partners.

81. Russia promotes broad mutually beneficial economic cooperation in the Asia-Pacific Region, which includes the opportunities offered by the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum.

82. Russia is committed to establishing a common, open and non-discriminatory economic partnership and joint development space for ASEAN, SCO and EAEU members with a view to ensuring that integration processes in Asia-Pacific and Eurasia are complementary.

83. Russia views the Asia-Europe Meeting and Conference on Interaction and Confidence-Building Measures in Asia as relevant mechanisms for developing multi-faceted practical cooperation with the Asia-Pacific States and intends to take an active part in these frameworks. But Afghanistan and Pakistan are mentioned rather in negative context.

97. The persisting instability in the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan after the withdrawal of all but a few international contingents poses a major security threat to Russia and other members of the CIS. The Russian Federation, together with the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, other interested states relying on the possibilities offered by the UN, CIS, CSTO, SCO and other international organizations will be consistent in its efforts to resolve as soon as possible the problems this country is facing, while respecting the rights and legitimate interests of all ethnic groups living in its territory so that it can enter post-conflict recovery as a sovereign, peaceful, neutral state with a sustainable economy and political system. Implementing comprehensive measures to mitigate the terrorist threat emanating from Afghanistan against other states, including neighbouring countries, as well as eliminate or substantially reduce the illicit production and trafficking of narcotic drugs is an integral part of these efforts. Russia is committed to further intensifying UN-led international efforts aimed at helping the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan and its neighbouring states counter these challenges.

And point 15 is about global security and threats: The global terrorist threat has reached a new high with the emergence of the Islamic State international terrorist organization and similar groups that have descended to an unprecedented level of cruelty in their violence. They aspire to create their own state and seek to consolidate their influence on a territory stretching from the shores of the Atlantic Ocean to Pakistan. The main effort in combating terrorism should be aimed at creating a broad international counter-terrorist coalition with a solid legal foundation, one that is based on effective and consistent inter-state cooperation without any political considerations or double standards, above all to prevent terrorism and extremism and counter the spread of radical ideas.

Next, consider the presidential Decree of 31.12.2015 N 683 “On the national security Strategy of the Russian Federation.” First of all, it should be pointed out that “as a Central element of the system of international relations, Russia sees the United Nations and its Security Council”.

It has a number of items on the South Asian region.

88. Russian Federation increases cooperation with BRICS partners (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa), RIC (Russia, India, China), Shanghai cooperation organization, Asia-Pacific economic cooperation forum, the G20 and other international institutions.

92. The Russian Federation attaches great importance to building the political and economic potential of the Shanghai organization of cooperation, stimulation within its framework of practical measures, contributing to the strengthening of mutual trust and partnerships in Central Asia, as well as the development of cooperation with member States, observers and partners.

Organizations, including in the form of dialogue and cooperation on a bilateral basis. Special attention is paid to the work with countries wishing to join the Organization as full members.

93. The Russian Federation is developing comprehensive partnership and strategic cooperation with The People’s Republic of China, considering them as a key factor in maintaining global and regional stability.

94. The Russian Federation attaches great importance to the privileged strategic partnership with the Republic of India.

95. The Russian Federation supports the establishment of reliable mechanisms in the Asia-Pacific region to ensure regional stability and security on a non-bloc basis, improving the effectiveness of political and economic cooperation with the countries of the region, expansion of cooperation in the field of science, education and culture, including in the framework of regional integration structures. Next is economic security Strategy of the Russian Federation for the period up to 2030 (Decree of the President of the Russian Federation of 13.05.2017. № 208).

– building an international legal system that meets the national interests of the Russian Federation economic relations, prevention of its fragmentation, weakening or selective application;

– expansion of partnership and integration relations within the framework of the Commonwealth of Independent States,

The Eurasian economic Union, BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa), Shanghai cooperation organization and other intergovernmental organizations; creation of regional and TRANS-regional integration associations in compliance with national interests of Russian Federation;

Next is the foreign economic strategy of the Russian Federation till 2020, prepared by the Ministry of Economic Development of the Russian Federation, issued in December 2008.

In the block devoted to Asia from South Asia only India is specified.

It is noted that Russian non-primary goods and services, including high-tech products, are traditionally in demand on the Indian market.

This creates opportunities for increasing supplies of the existing range of exports, as well as for diversification of the structure of trade. The main objectives are to expand Russia’s access to Indian markets and joint technology development in selected areas.

It is worth mentioning Doctrine of Information Security of the Russian Federation (Approved by Decree of the President of the Russian Federation No. 646 of December 5, 2016).15

28. A strategic objective of information security in the field of strategic stability and equal strategic partnership is to create a sustainable system of conflict-free inter-State relations in the information space.

29. The main thrusts of ensuring information security in the field of strategic stability and equal strategic partnership are the following:

– protecting the sovereignty of the Russian Federation in information space through nationally-owned and independent policy to pursue its national interests in the information sphere;

– taking part in establishing an international information security system capable of effectively countering the use of information technologies for military and political purposes that are contrary to international law, or for terrorist, extremist, criminal or other illegal purposes;

– creating international legal mechanisms taking into account the specific nature of information technologies and intended to prevent and settle conflicts between States in information space; promoting in international organizations the position of the Russian Federation advocating equitable and mutually beneficial cooperation of all interested parties in information sphere.

The fog and friction of diplomacy

At the same time, the actions and even intentions of Russia are often misunderstood and used by other parties to promote their own interest. For example, Hillary Clinton while working as Secretary of state after Vladimir Putin announced the creation of the Eurasian Economic Union in 2011 (it would be more correct to say the reform of the Customs Union), she said that Moscow will create the Soviet Union-2.

Thus, the situation with regard to Ukraine and Russia’s actions on the one hand, and the West on the other, describes well John J. Mearsheimer opinion, who pointed to the guilt of the West in the Ukrainian crisis.

“The United States and its European allies share most of the responsibility for the crisis. The taproot of the trouble is the enlargement of NATO, the central element of a larger strategy to move Ukraine out of Russia’s orbit and integrate it into the West. At the same time, the EU’s expansion eastward and the West’s backing of the pro-democracy movement in Ukraine — beginning with the Orange Revolution in 2004 – were critical elements, too.

The West’s triple package of policies – NATO enlargement, EU expansion, and democracy promotion — added fuel to a fire waiting to ignite.

This is Geopolitics 101: great powers are always sensitive to potential threats near their home territory. After all, the United States does not tolerate distant great powers deploying military forces anywhere in the Western Hemisphere, much less on its borders”.16

Emma Ashford also on the same side with John J. Mearsheimer, and noted that “today’s confrontational rhetoric and policies toward Russia often ignore reality and highlight the need for an alternative approach”.17

And Stephen Kotkin argues that “Russia today is not a revolutionary power threatening to overthrow the international order. Moscow operates within a familiar great-power school of international relations, one that prioritizes room for maneuver over morality and assumes the inevitability of conflict, the supremacy of hard power, and the cynicism of others’ motives. In certain places and on certain issues, Russia has the ability to thwart U.S. interests, but it does not even remotely approach the scale of the threat posed by the Soviet Union, so there is no need to respond to it with a new Cold War”.18

Realpolitik and Russia’s actions

As we can see from the official documents, India is given priority among the countries of the region. In practice, we also see close cooperation between Russia and India, especially in the sphere of arms supplies (70% of the arms in India are Soviet and Russian origin). Because of the traditional Indian-Pakistani confrontation and by virtue of the fact that during the cold war Pakistan belonged to the number of geopolitical opponents of the USSR, the Russian Federation’s relations with this country have not received the same scale of development and do not have the same traditions of relations like Russia has with India. Despite this, the basis for mutually beneficial relations in trade is stable – there are economic, energy and investment spheres between Russia and Pakistan.

From the geopolitical point of view, the North-Western regional segment, including Pakistan, is the most significant for Russia. Afghanistan and leading to Central Asia is a region that is particularly important for Russia, bordering Siberia and the Ural-Volga region.

Basic Russian prospects are seen in strategic cooperation with India, trade and economic cooperation with others states in the region. Potential risks are due to the likely destabilization of the situation in the North-West of South Asia, capable of “spread” to the Central Asian republics.

There is also a kind of risk associated with the aggravation of relations between India and Pakistan, in the extreme case, a military confrontation including the use of nuclear weapons.

Another threatening area for the region from the Russian point of view is humanitarian and environmental. For the moment refugees from Afghanistan, Pakistan or India have had no impact on Russian domestic policy, but on the international scale Russia always pays attention to this problem. In addition to natural disasters and cataclysms, including here the problem of piracy in the Northern Indian ocean.

Earlier it was predicted that in order to reduce regional tensions and balance its policies in South Asia, Russia, obviously, will strengthen economic cooperation with Pakistan, and will help it, in particular, in the construction of the gas pipeline from Iran and Turkmenistan, as well as providing assistance in organizing electricity supplies from Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan to Afghanistan and Pakistan.

After the launch of the Rogun hydroelectric power plant in Tajikistan in November 2018, this interaction is now close to practical embodiment. It has not excluded the implementation of other cooperation projects, in particular, through industry, as well as cooperation in security sphere with the growing use of the potential of SCO (Shanghai cooperation organization) and the “Dushanbe four” (Russia, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan).

Russian experience as mediator for water sharing between Central Asian countries may be utilized in South Asia too because of violating the Indus Water Treaty by India as well as problem with water flows after heavy rains from India into Bangladesh.

As for Pakistan, according to Russian experts, despite certain developments in the country such as higher education, including technical education, Pakistan, unlike India, has not found a high-tech niche in the world division of labour. Demand for the services of scientists, engineers and technicians comes mainly from the military-industrial, and especially the nuclear missile complex.19

This gap may be filled with Russian assistance too. The sale of weapons systems by Russia to South Asian States illustrates well the level of interaction between the countries.20 The Rosoboronexport company cooperates with four States, i.e. half of the countries of South Asia. India since 1947, Pakistan since 1948, Sri Lanka since 1957 and Bangladesh since 1972. It is significant that Rosoboronexport makes no sales to the States, which pursues a hostile policy towards Russia.

Russia is interested in enhancing the strategic capacity of such organizations as SCO and The Conference on Interaction and Confidence-Building Measures in Asia to form a new security architecture for Greater Eurasia. This approach is directly linked to the realization of the Russian initiative of “integrating integrations”, which takes into account all actors and all possible changes in the balance of powers in the region, including natural leadership changes.21

Transport and energy routes (built and projected too) may be implemented and synchronized in the context of Eurasian Economic Union led by Russia and New Silk Road led by China.

As a rule, considering the interests of Russia in the region, analysts mention only material factors. Actually there is a great interest on the part of Moscow in intellectual cooperation. Denoting the course to create a multipolar world order Russia needs semantic filling of this concept that is not possible without the active participation of the outside scientific and expert community of South Asian countries.

Although multipolarity can be interpreted in different ways, the main criterion is the attitude toward the United States and the willingness to challenge Washington. For example, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi has repeatedly stated that India is committed to multipolarity and he expressed flattering compliments to Russia as a country that is one of the main poles of influence in the world. But in fact India follows the doctrine of multilateralism, actually fulfilling the imperatives of the Obama administration. Although India did not support sanctions against Russia and was not afraid of sanctions by the United States for the contract of the purchase of the S-400 systems, cooperation that is more intensively developing between the US and Israel than with its neighbors in Eurasia.

Pakistan, on the contrary, took the position of sovereignty and denied its critics in Washington, so it aroused considerable interest from Russia as an emergent power. This window of opportunity can be favorably used by two parties.

In the current geopolitical situation and in light of the irresponsible behavior of the United States (and their satellites) on the world stage, the implementation of joint Russian-Pakistani projects, including military cooperation, will help strengthen security in Eurasia in the interests of all participants.22

Non-Western theories of international relations as sovereign intellectual developments supporting the discourse on multipolarity also will be in great demand in the academic circles of Russia.

In addition, discussions on non-Western approaches to international relations and alternative political theories can not only be a bond for a dialogue of a new quality between Russia and the countries of South Asia, but also lay additional foundations for rethinking regionalism.

Still, South Asia is part of Eurasia, and Russia is interested in strengthening its stability and the predictability of the actions of all its actors.

https://www.geopolitica.ru/en/article/geopolitics-south-asia-and-interests-russia

___

1 Michael Mann. 2014. South Asia’s Modern History: Thematic Perspectives. Taylor & Francis. pp. 13–15.

2 Prashanth Parameswaran. Trump’s Indo-Pacific Strategy Challenge in the Spotlight at 2018 Shangri-La Dialogue. The Diplomat. June 05, 2018. Available at: https://thediplomat.com/2018/06/trumps-indo-pacific-strategy-challenge-in-the-spotlight-at-2018-shangri-la-dialogue/ [Accessed 23 October 2018].

3 Tariq Mehmood. Regionalization of Peacekeeping Operations in South Asia // Margalla Papers Vol. XX, 2016. National Defence University Islamabad. P. 205.

5 Ash Carter. Reflections on American Grand Strategy in Asia. Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Special Report. October 2018. P. 4. Available at: https://www.belfercenter.org/sites/default/files/files/publication/ReflectionsonAmericanGrandStrategyinAsia_0.pdf [Accessed 3 November 2018].

6 Ibidem. P. 5.

7 Ibidem. P. 14.

8 Ibidem. P. 32.

9 Ibidem. P. 29.

10 Kaplan Robert D. 1996. The Ends of the Earth: A Journey at the Dawn of the Twenty- first Century. Random House, Inc. P. 337.

11 Georgekutty M. V. Problematising South Asian Area Studies // SAJD, 2013. P. 40.

12 Rohit K Dasgupta, Remembering Benedict Anderson and his Influence on South Asian Studies // Theory, Culture & Society 0(0), 2016. P. 3.

13 Gopal Anand. The Battle for Afghanistan: Militancy and Conflict in Kandaghar. Counterterrorism Strategy Initiative Policy Paper. Washington, DC: New America Foundation, November 2010. P. 14.

14 The Foreign Policy Concept of the Russian Federation (approved by President of the Russian Federation Vladimir Putin on November 30, 2016). Available at: http://www.mid.ru/en/foreign_policy/official_documents/-/asset_publisher/CptICkB6BZ29/content/id/2542248 [Accessed 23 November 2018].

15 Doctrine of Information Security of the Russian Federation (Approved by Decree of the President of the Russian Federation No. 646 of December 5, 2016) 5 December 2016. Available at: http://www.mid.ru/en/foreign_policy/official_documents/-/asset_publisher/CptICkB6BZ29/content/id/2563163 [Accessed 6 October 2018].

16 John J. Mearsheimer. Why the Ukraine Crisis Is the West’s Fault. Foreign Affairs. September/October 2014 Issue. Available at: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/russia-fsu/2014-08-18/why-ukraine-crisis-west-s-fault [Accessed 6 October 2018].

17 Emma Ashford. How Reflexive Hostility to Russia Harms U.S. Interests. Foreign Affairs. April 20, 2018. Available at: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/russian-federation/2018-04-20/how-reflexive-hostility-russia-harms-us-interests [Accessed 6 October 2018].

18 Stephen Kotkin. Russia’s Perpetual Geopolitics. Putin Returns to the Historical Pattern. Foreign Affairs. May/June 2016 Issue. Available at: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/ukraine/2016-04-18/russias-perpetual-geopolitics [Accessed 6 October 2018].

19 Вячеслав Белокреницкий. Южная Азия 2013–2020: возможности и риски для России. 7 июля 2013 г. Available at:

http://russiancouncil.ru/analytics-and-comments/analytics/yuzhnaya-aziya-2013-2020-vozmozhnosti-i-riski-dlya-rossii/ [Accessed 23 November 2018].

21 Savin, Leonid. Russian security frame for Black sea region. Geopolitica.ru. 06.12.2017 Available at: https://www.geopolitica.ru/en/article/russian-security-frame-black-sea-region [Accessed 6 October 2018].

22 Savin, Leonid. Pakistan-Russian friendship. The Nation. November 05, 2018. Available at: https://nation.com.pk/05-Nov-2018/pakistan-russian-friendship [Accessed 23 November 2018].

Publishsed in “Conflict and Cooperation in South Asia. Role of Major Powers. Islamabad: IPRI, 2019. P. 153 – 180.

TheAltWorld

TheAltWorld

0 thoughts on “Geopolitics of South Asia and Interests of Russia”