My Experiments With Hacking Capitalism

Listen to this article:

I just realized I’ve never really written about how I make a living doing what I do, which is odd because it’s easily the most interesting aspect of my weird little operation here. I’ll put the information out there just in case it’s useful to anybody.

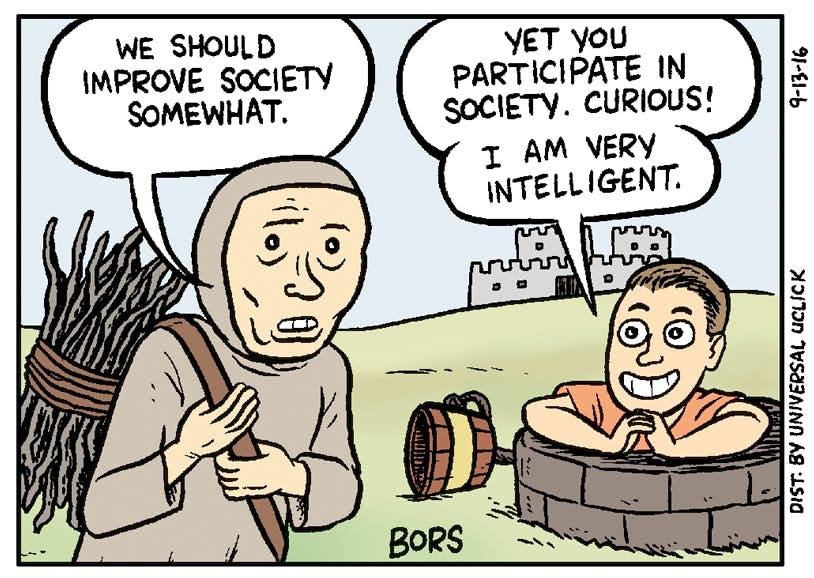

Like anyone else who criticizes capitalism within earshot of hardcore capitalism enthusiasts, I get the “and yet you participate in capitalism ha ha” line all the time. They claim that because I have links to Patreon and Paypal at the bottom of my articles I am hypocritical for criticizing capitalism, which is silly for a number of reasons.

It’s silly because we live in a capitalist society which requires participation in capitalism to engage in, so it’s a lot like telling prisoners who complain the prison system that they are being hypocritical because they live in prison. It’s also silly because it implies that the only people who can criticize the status quo are those living in a log cabin in the woods with no electricity eating squirrel meat and yelling their grievances into a hole in the ground.

And, in my case, it’s also silly because it’s less true of me than it is of most people.

I make my living entirely from the goodwill of other people. I work as hard as most people, but I don’t charge money for my labor; I work for free and demand nothing from anyone who enjoys the fruits of my labor. All my work is free to view, free to republish, free to use, free to alter, on no conditions whatsoever; even my books are comprised entirely of stuff that’s free to view online. There is no trade, and there is no exchange; you already have the product. I just have a digital tip jar at the bottom of every article that people can toss a few coins into if they want to.

I decided early on in this commentary gig that I wanted to write about the healthiest things I can possibly write about from the healthiest parts of myself, and if I’m going to get paid I want it to be by the healthiest impulses of the healthiest sort of people. In my case that means writing from every angle I can about the ways our society is unhealthy and how it can move toward health, and it means doing so in full dependence on the goodwill of people who care about the same thing.

As near as I can tell the major problems with the world I am leaving to my children ultimately boil down to the fact that money tends to elevate the very worst kinds of people: those who are willing to step on anyone to get ahead, even if it means impoverishing everybody else, or starting wars, or destroying the ecosystem we all depend on for survival. My goal has been to try and “hack” this trend by getting money to reward health instead, thereby allowing me to embody the opposite of the disease and proving that a better way is possible.

Because money is power and money rewards sociopathy, we wind up ruled by greedy sociopaths. This problem is further exacerbated by the fact that wealth has been shown to kill empathy in those who have it, which makes sense if you consider how money functions as a kind of prosthetic goodwill currency. Without a lot of money you depend on the goodwill of your neighbors to get by; you need to always be attuned to what their needs are, how you can help them, and how they’re feeling toward you in order to make sure they’ll help you fix your car when it breaks down or whatever. If you are wealthy you don’t need to think about goodwill at all, so that attunement to other people’s needs and feelings will atrophy.

By contrast, in societies that aren’t dominated by money, goodwill is the prevailing currency, and sociopaths tend to wind up dead. From Scientific American:

In a 1976 study anthropologist Jane M. Murphy, then at Harvard University, found that an isolated group of Yupik-speaking Inuits near the Bering Strait had a term (kunlangeta) they used to describe “a man who … repeatedly lies and cheats and steals things and … takes sexual advantage of many women—someone who does not pay attention to reprimands and who is always being brought to the elders for punishment.” When Murphy asked an Inuit what the group would typically do with a kunlangeta, he replied, “Somebody would have pushed him off the ice when nobody else was looking.”

In such tribal cultures your worth is measured not by how much money you have, but by the extent to which you improve the quality of life for those around you. If you make life pleasant for the collective you’ll receive plenty of goodwill from them, and if you make life unpleasant for them you run out of goodwill and get pushed off the ice. But in our society a kunlangeta’s disregard for goodwill and his willingness to do anything for profit could make him a CEO.

My goal here is to get by on goodwill currency instead of kunlangeta currency, while hopefully helping to move us out of our kunlangeta way of life.

This is why I don’t have any tiers or rewards on my Patreon page; it’s important to what I’m doing here that it be an entirely goodwill relationship on both ends, because in my experience the healthiest relationships all come from a mutual desire to give freely while the unhealthiest are “you give me that I’ll give you this” transactional relationships. I put just as much effort into my work whether I get a lot of money on a given day or none at all, and patrons get the same whether they give me two dollars or two hundred. That way we’re all operating entirely from intrinsic motivation, driven by the inner rewards of having done something helpful and advancing something we value, rather than the extrinsic motivation model of capitalism that is driving our world toward disaster.

And that’s ultimately what I’d like to see for humanity going forward: a world where we’re not stepping on each other and our ecosystem in pursuit of profit, but collaborating with each other and with our ecosystem out of intrinsic motivation toward the common good of all beings. My way of life is the best personal testament I can offer that such a world is possible.

And seeing that it is possible is the first step. Mark Fisher writes:

Watching Children of Men, we are inevitably reminded of the phrase attributed to Fredric Jameson and Slavoj Žižek, that it is easier to imagine the end of the world than it is to imagine the end of capitalism. That slogan captures precisely what I mean by ‘capitalist realism’: the widespread sense that not only is capitalism the only viable political and economic system, but also that it is now impossible even to imagine a coherent alternative to it.

I am trying to help us all imagine a coherent alternative to it. I don’t know precisely to what extent my path can be traveled by other people, much less by the entirety of our species. But walking this path for myself has given me a lot of hope that I can leave my children a much healthier world.

https://caitlinjohnstone.substack.com/p/my-experiments-with-hacking-capitalism

TheAltWorld

TheAltWorld

0 thoughts on “My Experiments With Hacking Capitalism”