The Washington Post‘s Josh Rogin (8/13/20) writes that “Biden and Harris, if they are elected, will have a chance to prove that Democratic muscular liberalism is still the right approach.”

Writing in the Washington Post , pro-war columnist Josh Rogin appeared relieved that Joe Biden picked Kamala Harris as his running mate for November—as opposed to a progressive like Elizabeth Warren or Bernie Sanders, who would have called for cutting military budgets, fewer US interventions and the withdrawal of troops stationed abroad. Biden and Harris, he explained, will together pursue a “robust” foreign policy agenda.

Harris is described approvingly by one source as “pragmatic” (another media codeword—FAIR.org, 8/21/19), and together, Rogin notes, she and Biden can prove that “muscular liberalism is still the right approach.” What that actually means in practice, he is a little vague on, though he does suggest that will entail “aggressively” “confronting” nuclear powers Russia and China.

“Muscular,” along with similar words like “robust,” are commonly used in political reporting, especially with regards to foreign policy. They are inherently positive descriptions, conveying strength and confidence, their opposites being “weak,” “feeble” or “decrepit.” It is obvious which have the better connotations. This is a real problem, because all too regularly the words are used as euphemisms to sugarcoat inflicting violence around the world.

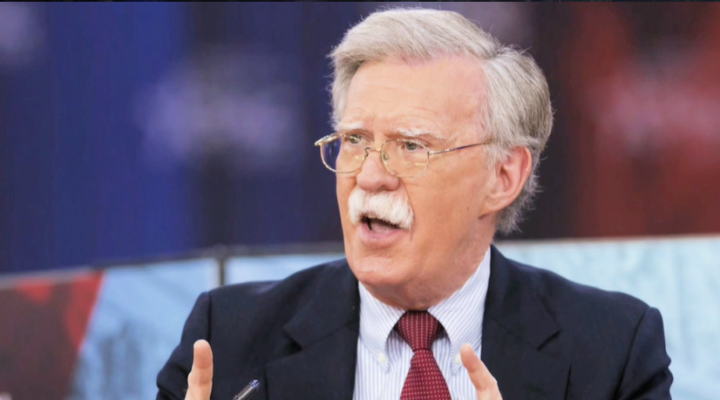

Often the consequences of such a policy are not stated, as when CBS News (6/17/16) reported that John Kerry recommended “a more muscular US role in Syria,” or when a guest on the Rachel Maddow Show (6/18/14) described former Vice President Dick Cheney as wishing for a more “muscular policy” for the US in Iraq. Thus, when CBS’s Face the Nation (3/23/18) aired a segment entitled, “Trump Surrounding Himself With ‘More Muscular’ Foreign Policy Team,” a naif or a foreigner might be forgiven for thinking Jesse Ventura or Arnold Schwarzenegger was advising the president. And when the BBC (12/18/17) reported on the US’s “muscular engagement” with the world, they were not describing a new workout plan.

CBS (3/23/18) described Trump’s hiring hyper-interventionist John Bolton as signaling a “more muscular” foreign policy team.

Sometimes, however, journalists made explicit what such a foreign policy would consist of. The New York Times (5/14/15), for instance, described Republican presidential hopeful Marco Rubio as offering “a robust and muscular foreign policy,” including the end of normalization with Cuba, a hike in military spending and reauthorizing the PATRIOT Act. The Times is a repeat offender in whitewashing the Florida senator’s often disturbing policies; in 2019 it described his advocacy for further sanctions and military intervention in Venezuela as “muscular policy tools” (New York Times, 1/29/19). By this time, the sanctions had already killed an estimated 40,000 people and would go on to kill over 100,000. What about blocking the import of medicines is “muscular”? “Sociopathic” might be a better adjective. Support for regime change in Venezuela is bipartisan, however, with Bloomberg’s Eli Lake (8/3/20) recently noting that support for a “democratic transition” there would be more “steadfast” under a Biden administration.

The result of “muscular” and “robust” policies can also be seen all over the Middle East. In 2017, Trump reversed his earlier promise to pull US troops out of Afghanistan, instead announcing his own surge, having just dropped the largest non-nuclear bomb in human history on the country. The Washington Post (8/21/17) described his decision as “muscular but vague.” On Syria, the New York Times (4/21/17) pondered whether a more or less muscular approach would bring better results. And when Trump ordered B-52 bombers to Iran’s doorstep, CBS anchor Margaret Brennan (5/12/19) asked a guest what he thought of the president’s “muscular response” to Iranian provocation.

Or you can also read about Saudi Arabia’s muscular foreign policy in Yemen (LA Times, 4/20/15, 8/11/19; BBC, 4/21/15), thought to have killed hundreds of thousands of people. Likewise, on one of the many recent occasions when Israel bombed Gaza, the Washington Post (3/26/19) noted that some Israeli politicians were calling for an even more “muscular response”—combining the “muscular” media trope with the convention that the US and its allies never initiate violence themselves, but only ever “respond” to enemy provocation (FAIR.org, 6/6/19, 8/21/20).

So reflexive is this media whitewashing of state violence that it is even applied to official enemies. For instance, in an article explaining the rise of Russian president Vladimir Putin, CNN (8/8/19) wrote: “What explained Putin’s surge in popularity over those crucial early months? One factor was clear: Putin’s muscular response to domestic terrorism.” That “muscular response,” CNN explicitly stated, included when “Russian forces leveled the [Chechen] rebel capital of Grozny,” which is thought to have killed around 9,000 people.

The word is also sometimes used in reference to domestic programs as well, but generally only when involving oppressing the powerless. In 2012, Fox News (1/10/12) reported that immigration activists were unhappy with President Barack Obama’s “muscular deportation policy” (which saw more people deported than ever before). Likewise, in the wake of masked federal agents abducting people off Portland’s streets, the New Yorker (7/24/20) worried about the “ever more muscular immigration-enforcement presence in US life.”

“Weak” is used in corporate media as a synonym for “diplomatic” (Fox Business, 8/18/20).

While advocating wholesale violence is “robust” or “muscular” in media speak, opposing it is inherently “weak” and worthy of condemnation. A case in point is Bernie Sanders, whose “weak foreign policy,” according to Business Insider (3/15/20), was a serious black mark against him. Examples of his weakness, it noted, include “an obvious commitment to rejoin the Iran deal” and ending Saudi attacks on Yemen.

More scandalous, apparently, were his “controversial comments” on Venezuela, Bolivia and Cuba, comments that amounted to not endorsing US regime change efforts against sovereign nations. This, for Business Insider columnist and former US diplomat Brett Bruen, made him a unserious presidential candidate.

And while Rogin and the WaPo might have described Biden as robust on foreign policy, Trump did not see it that way; the president this month telling Fox Business (8/18/20) his opponent was “weak” on the issue. The reason? Biden would pursue a diplomatic solution with Iran, like Obama did.

There is nothing inherently strong about destroying or terrorizing other nations, and nothing weak about opposing it. But our hawkish corporate media continue to present it as such, therefore subtly manufacturing consent for continued conflicts around the world. The next time you hear someone on corporate media praising a “muscular,” or “robust” foreign policy, be on the alert: They might be trying to sell you another war.

TheAltWorld

TheAltWorld

0 thoughts on “‘Muscular’ Foreign Policy: Media Codeword for Violence Abroad”