The enduring myths that continue to drive western foreign policy

Britain’s ‘appeasement’ of Hitler and the US strongarming of the USSR in the Cuban missile crisis are simplified, historical myths. Then, as now, concessions and negotiation are key

Western foreign policymaking in the 21st century is still largely influenced by the lessons learned from two crucial events that occurred in the previous century: the conference with Hitler in Munich in September 1938; and the Cuban missile crisis in October 1962, when the US and the Soviet Union came close to a nuclear war.

Generations of historians have poured over both for decades. But their scholarship notwithstanding, both events have generated their own mythology, which is not borne out by what happened at the time.

The Munich conference has obsessed generations of western politicians, diplomats and strategic thinkers, preeminently, but not exclusively, Anglo-Americans. It has often been solemnly invoked as a fundamental warning against any form of concession toward irredeemably evil foes.

During the conference, the UK and France agreed to Nazi Germany’s annexation of the Sudetenland region in western Czechoslovakia, inhabited by an old German minority.

London and Paris claimed that, as a result, war had been averted. But even in 1938, the conference was hugely controversial. There was a powerful speech by Winston Churchill, then a backbench MP, who called it “a total and unmitigated defeat”.

Condemned to perpetual infamy

Munich did not prevent Adolf Hitler from invading Poland in September 1939, triggering the start of the Second World War, after which the Munich Conference assumed quite different and far more sinister connotations. The then prime ministers of Britain and France, Neville Chamberlain and Edouard Daladier respectively, were both condemned to perpetual infamy for their weakness towards Hitler.

The catchword for the conference became “appeasement”, and it was soon transformed into a symbol of the futility of talking to totalitarian or autocratic states. The tense relationship that the West has today with Russia, China and Iran is, to a large extent, still framed by the legacy of Munich.

But go back to September 1938 and the perspective changes. Hitler was appeased not because European democracies were weak or cowardly, but because the UK, especially, was not yet ready for war. Munich gave Britain a further year to better prepare for an armed conflict that appeared more and more inevitable.

How precious this extra year was became apparent in 1940, when the RAF defeated the Luftwaffe in the Battle of Britain, the Germans lost air superiority over the English Channel and a Nazi invasion was prevented. It was one of the turning points of the war according to Andreas Hillgruber, the leading German historian of that period. Its implication was soon understood by Hitler, and it paved the way for his most fateful decision: the invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941.

Janan Ganesh, a political columnist for the Financial Times, recently highlighted again this crucial aspect, buried for decades by the official historical narrative. He expressed hope that Munich’s real lesson might be finally learned by current western leaderships. Yet every time an international crisis occurs, Munich still comes to stand for the folly of compromise and the wisdom of toughness.

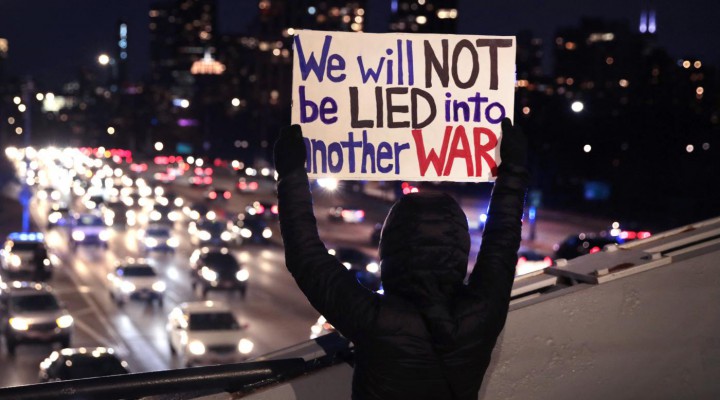

Anybody who nurtured doubts on the wisdom of wars in Iraq and Libya, in 2003 and 2011 respectively, or resisted acting in Syria in 2013, has been labelled as a dangerous appeaser, with Munich 1938 very much in mind.

Iran nuclear deal

Republican policymakers in the US and Israeli centre-right politicians did the same with the nuclear deal signed with Iran (the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action or JCPOA) in 2015. Seven years later, they still appear adamantly opposed to any deal with Iran by invoking the precedent set in 1938, and they emphasise the JCPOA’s alleged failure in curbing Iran’s nuclear programme.

Alas, they omit to explain that they, and no one else, are to blame for such an outcome. Former US President Donald Trump blew the sanctity of US decision-making apart by admitting that on Iran he had been misled by former Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

In 1962, President John F Kennedy’s steely determination and naval blockade, as well as US military superiority, forced the USSR’s leader, Nikita Khrushchev, to capitulate and stop the ongoing deployment of Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba. The outcome became an enduring symbol of American triumph and Soviet defeat, a landmark event that has dominated US foreign and security policy elaboration for decades to come.

In the words of one of most eminent American foreign policy scholars, the late Leslie Gelb, president emeritus of the Council on Foreign Relations and the first to openly debunk such views as a myth 10 years ago, the Cuban missile crisis “deified military power and willpower and denigrated the give-and-take of diplomacy. It set a standard for toughness and risky duelling with bad guys”.

This lesson was repeated by almost all US policymakers, Congress members, diplomats, military leaders, media commentators, think-tankers and academics – in other words, the US foreign policy and security establishment.

The crisis coined the slogan “no compromise with the devil”. What was applied to Khrushchev six decades ago is considered applicable to Russia’s President Vladimir Putin today. Other important corollaries of the Cuban missile crisis are that “concessions are a sign of weakness” and “any dealing must take place from a position of strength”.

Compromise can work

For the record, the narrative about the Cuban missile crisis told since 1962 is a myth because it was ended not by Moscow’s unconditional surrender to US demands, but by mutual concessions.

The Soviets withdrew their missiles from Cuba in return for formal US pledges not to invade the island (attempted the year before at the Bay of Pigs) and to remove their Jupiter intermediate-range nuclear missiles from Turkey, bordering the then Soviet Union. In fact, the Soviets obtained two concessions in exchange for one.

Since 1962, then, US foreign policymaking has been largely built upon such myths. As Gelb wrote: “For too long, US foreign-policy debates have lionised threats and confrontation and minimised realistic compromise”.

Historical evidence shows that compromise is not always bad and, as seen with the Cuban missile crisis, it can work. This important lesson, then, should be better learned.

But even relatively less hawkish US presidents such as Joe Biden have problems embracing such views, as shown by his refusal to rescind Trump’s decision and rejoin the JCPOA unconditionally. The negotiations currently underway in Vienna are being derailed by the obsessive search for positions of strength.

As Ganesh wisely concludes: “The strength-at-all-costs school of foreign policy is not just ugly, it is counterproductive.”

Dangerous and counterproductive

Being resolute and steadfast is important in deterring enemies and allowing nations to credibly assert principles and interests. However, both qualities become hindrances when they are put on autopilot. Blithely and stupidly implemented, they become dangerous and counterproductive.

Munich and Cuba keep good company with other myths, such as the famous domino theory, which embroiled the US in an unsuccessful 10-year-long war in Vietnam.

Such myths are part of an unsettling cognitive dissonance that for too long has been haunting US foreign and security policy. A recent essay in the National Interest magazine described it as “the creation of ‘meta-narratives’, all-encompassing frameworks of thought and analysis into which a wide range of quite different issues are fitted [and]… focused on one supposedly monolithic, universal, and overwhelmingly powerful enemy, which it is necessary to confront everywhere”.

An essential part of these meta-narratives scripts is also a hyperbolic exaggeration of the threat, and a systemic scaremongering of public opinion.

Presently, well-oiled Manichean meta-narratives are targeting China’s rise, and, nostalgically, Russia’s “revanchism”. The two countries are sources of problems, for sure, but the West has unsurprisingly and unnecessarily portrayed the geopolitics involved as global apocalyptic struggles of good democracies against evil autocracies, a view bordering on nonsense.

It is human nature to misread history and to create myths. But when myth-making becomes systemic – as the critical western relationship with Russia and China is now proving – it can be dangerous. And fateful, too.

https://www.middleeasteye.net/opinion/west-iran-china-russia-myths-foreign-policymaking

TheAltWorld

TheAltWorld

0 thoughts on “The enduring myths that continue to drive western foreign policy”