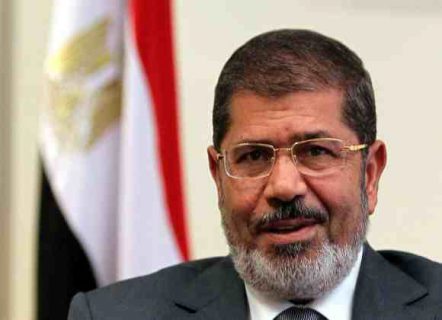

Remembering Muhammad Morsi

Egypt’s late former president was the victim of gross injustice

I confess that I was and remain fond of Muhammad Morsi, Egypt’s former and only democratically elected president. I was shocked to hear the news on Monday evening that he had collapsed and died in a courtroom, dressed in blue prisoners’ uniform, after delivering a 20-minute defence in which he exposed all the charges levelled against him as ‘fabrications’ by his political foes and the public prosecution.

I met President Morsi twice. The first time was in September 2012 in Ankara, where I had been invited to attend the ruling Justice and Development party’s annual conference. The second was on 3 June 2013 at the Ittihadiya Palace in Cairo, just a month or some before he was deposed.

On the first occasion I was seated in the cafeteria of the Marriot Hotel in the Turkish capital, where I and a huge number of other guests were staying. The most prominent of them was Morsi, and he was accorded a special welcome by Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who was just coming to the end of his second term as Turkey’s prime minister. Suddenly, there was a commotion in the lobby, and the Egyptian president appeared surrounded by a posse of aides and bodyguards. Our eyes met, and he changed course and strode over towards me smiling. He embraced me, and jokingly admonished me for not having visited Egypt to congratulate him on winning the presidential election. He took me up in the elevator with him to his suite for a brief conversation. He was preparing to return to Cairo as he was only spending a few hours in Ankara.

President Morsi asked me again why I had not visited Cairo, and I replied that the answer was simple: his predecessor Hosni Mubarak had done me the honour of giving me a prominent place on the blacklist of people banned from entering Egypt. He laughed, and assured me the list would be torn up. He declared he was inviting me to visit Egypt, that I had many admirers there and should consider it my own country, and that there would be no more blacklists from now on. Egypt was entering a new era, he said, and was now a different place. I thanked him and took my leave hoping to meet again in Egypt.

I was a while before I took up the invitation, as Egypt was in a state of constant turmoil. No sooner had one protest ended when another began. But at the beginning of June I decided to make my way to Cairo, which was teeming with visitor from all over the world, and was witnessing an unprecedented media renaissance. Endless television talkshows testified to a degree of openness and freedom of expression which neither Egypt nor any other Arab country had experienced before.

I told my friend Hassanein Kroum — the Cairo bureau chief of al-Quds al-Arabinewspaper of which I was editor-in-chief – that I wanted to meet President Morsi at his own invitation. He turned pale, and did not appreciate the request. An old Nasserist, he was no fan of the Muslim Brotherhood, and made no secret of the fact. But he said he would contact the president’s office and pass on the request. Within the hour they got back to him and said the president would be waiting for us at the Ittihadiya Palace at noon the following day.

Hassanein refused to accompany me there. You go on your own, he said, insisting that he did not recognise the president and had no desire to meet him. He reiterated his opposition to the Muslim Brotherhood, and quipped “you’re welcome to them.”

I was driven to the presidential palace in a car sent by protocol. I was not searched when I entered, other than passing through a metal detector accompanied by an aide. I was met by a well-dressed man carrying a briefcase bulging with documents. He introduced himself as Gen. Murad Muwafi, head of the General Intelligence Department and successor to the infamous Omar Suleiman. He gave me a typically jocular Egyptian greeting, and I joked back that I had a favour to ask him: that I should not be given a hard time by his people at the airport when I leave. He laughed and assured me that nobody would bother me.

President Morsi’s office was very modestly furnished. I sat on a sofa opposite him, with only his bureau chief Dr. Yaser Ali present, and we talked for around an hour. He was friendly and amiable, like the great majority of ordinary Egyptians. He spoke of his aspirations to reform the economy, re-industrialise the country and make it self-sufficient, especially in food production. He said he wanted to subsidise Egyptian farmers to produce grain to lessen the country’s dependence on cheap imported American wheat, and discussed a range of other issues.

As soon as I left the Ittihadiya Palace my mobile phone began ringing repeatedly. I do not answer calls from numbers I do not recognise so ignored them. Then a colleague called from London saying that Gen. Abdelaziz Seifeddin, a member of the military council and head of the military industrialisation organisation, and been trying to get in touch with me and wanted me to call him back. He had indeed been the anonymous caller. He invited me to dinner that evening with a group of his colleagues at the Officers’ Club in Heliopolis. One of the people present was to have been Gen. Abdelfattah as-Sisi, but I was told he had been summoned by Morsi to an emergency meeting about the ‘crisis’ over Ethiopia’s Rennaissance Dam. I left for London the following day and have not been back since to the Egyptian capital, where I spent the best years of my life as a university student and which holds a special place in my heart.

Gen. Seifeddin and his colleagues were friendly, courteous and hospitable. I recall that the only other civilian present was former information minister Dr. Usama Haikal. But I gathered during the course of the conversation that plans were afoot to depose Morsi and were at an advanced stage.

I was never a partisan of the Muslim Brotherhood. But I still believe that President Morsi, like many of his colleagues, was subjected to a gross injustice by being jailed and hauled humiliatingly before the courts, while people who looted the country and persecuted and committed crimes against its people run free. He did his best, got some things wrong and some things right. I disagree with many of his policies, but he never deserved the harsh mistreatment to which he was subjected, which violates all norms of justice and human rights.

I am well aware that this will displease many people. It may well ensure I remain firmly on that blacklist of travellers banned from visiting Egypt. But the truth has to be told.

https://www.raialyoum.com/index.php/remembering-muhammad-morsi/

TheAltWorld

TheAltWorld

0 thoughts on “Remembering Muhammad Morsi”